One of the pleasures of running this blog is the chance to engage with readers all over the world, who are able to share with me what's happening in their countries. The phenomenon I discuss here -- from participatory culture and politics to new media literacies to transmedia entertainment -- are playing out right now on a global scale. Thanks to these contacts, I have been able to share with my readers new developments in Russia, China, India, Poland, among many other examples, and I look forward to sharing other such cases in the future. Recently, I have corresponded with Éverly Pegoraro who has been researching the Steampunk scene in Brazil. And after some back and forth, I am happy to be able to share with you today some of her findings -- in words and images.

By the way, readers in Brazil may be interested to know that there is now a Portuguese edition of our most recent book -- Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture (with Sam Ford and Joshua Green)-- which is published there as Cultura da Conexão: Criando Valor e Significado por Meio da Mídia Propagável. You can learn more at the Aleph website. Thanks so much to our friend, Maurico Mota, for his hard work to make this book approachable to our friends down in Brazil.

Steampunk scene in Brazil: strategies of sociality by Éverly Pegoraro

What motivates steampunks? For some, just nostalgia. For others, daydreams. Amid fans and critics, the fact is that steampunk and other retrofuturistic movements extrapolate elements from the literary imagination as the basis for generating creative urban experiences. A meaningful example of this process may be perceived in Brazil. The steampunk "scene" in Brazil has already a substantial number of participants, spread across 13 states. Steamers, as they are known here amongst fans, participate in many activities.

Each Brazilian state holds a different group of steamers. For the past three years, I’ve had the opportunity to follow one of the most active steamer . groups in Paraná state in southern Brazil, Steampunk Council of Paraná Lodge. In this space, generously provided by Professor Jenkins, I will share some impressions about the research, which is part of my doctorate thesis.

Unlike other countries, Brazilian steamers are organized in lodges (a Masonry inspiration) in each State, which are administered by local councils. All are supported by Steampunk Council. The Steampunk Council’s mission is summarized on their official web site:

The Steampunk Council was conceived with the central idea of democratization, flexibility and sustainability of steampunk movement. It is less an organization and more a concept, on which representatives of steampunk community can create their lodges, as the cells are called from the concept of the Council. [ ... ] The Steampunk Council's mission is to provide mechanisms for the dissemination of steampunk culture, provide reference material, promote all sorts of related events, encouraging cultural production of this sort of subjectivity and paying tribute to all those who create and produce material of Steampunk culture in all possible forms. (Available at http://www.steampunk.com.br/conselho-steampunk/)

Each regional group is autonomous to develop their own activities. The Steampunk Council of Paraná Lodge has existed for about four years and is managed by a group of the most active founding members. Besides them, there are many participants, some more regular and active (about 25 people), others only occasional visitors. Adopting the fluid, ephemeral and diversified characteristics of neotribes characterized by Maffesoli (1987), they form a heterogeneous group, across genders, ethnicities and ages (ranging from 14 to 50 years). Members are from different social classes, studying and/or working in many areas, such as writers, musicians, housewives, professors, and service providers.

As organized groups, they have the opportunity to create more permanent social ties than the relative ephemerality of the neotribos. This is a strong characteristic of Paraná’s group. The several proposed activities during the year encourage face to face interaction amongst the participants and create spaces where each discovers and develops artistic, literary, media production skills.

The Steamers’ creations blend the imagery of the nineteenth century, the individual preferences of media culture and the creativity of each participant. The Victorian aesthetic is strongly present in this urban culture, especially in the costumes and in the context of the stories. But steampunk enables a wide dimension of contextualization that are not directly inserted in Victorian Era.

Therefore, the selection of this period is not exclusively due to the visual. Steamers say they seek values from the Victorian imaginary. They want more romanticism, sensibility and personal investment -- in other words, less mechanical and utilitarian relationships.

[Steampunk] refers to a time when people cared more about delicacy, gentleness, there had been a different culture, a more educated one. I find it interesting to extrapolate the technology of this period and advance it as if it had been nothing after, to increase the capacity of a technology that actually has not developed much. I find it interesting to explore more things that sometimes were not explored in the past. (Brazilian steamer) What fascinates me is the Victorian aesthetic, the well done style, with the smallest details, it has the seriousness of the men, the femininity of the women, the clothes […] the court society, the social rules. And there is also the convenience of the technology how we have today, the clothes are not made by hand, not everything is very expensive, we have the benefits of communication, medicine, entertainment, movie theaters. (Brazilian steamer)

We see the old aesthetic is beautiful, more farfetched. A time when people had more free time to take care of themselves, but the values were different. It's interesting you deal with an older aesthetic, but with current values, especially for women. The corset is nice, but nobody wants to live as it was before. So, it's cool to have that aesthetic, an aesthetic that people will look strange, for it’s old, but with values […] the female steampunk characters are not housewives, all professions in steampunk can be applied for men or for women.(Brazilian steamer)

The interviewees' statements above indicate an attempt to retrieve the values and behaviors of an idealized past. Such desires suggest the search for a less rationalist and mechanical subjectivity and the need to invest more deeply in relationships.

Homi K. Bhabha (2011) offers some interesting clues to consider the social articulations that occur in these inter-spaces of difference and minorities, in which there are complex processes of negotiation and cultural hybridisms. He conceives such cultural hybridism as a third space that enables new positions of meaning and representation. The negotiations that take place in these spaces allow hybrid agencies that do not seek cultural supremacy. Such movements are articulated in the “arts of the present”, defined by the author as the performances by which different minority group elaborates strategies of survival, identity formation, political contestation, social relations, and aesthetic manifestations. The steamers below talk about why they participate in this urban culture:

We're putting a question to rethink who we are, it’s not to think who we may be in the future, it’s to rethink who we are today. Which were our real choices in the past that brought us here, and based on which choices we could have made. That's what draws me into steampunk. (Brazilian steamer)

I think it's a fascination for a time that is chronologically so close, but so radically different from our reality. (Brazilian steamer writer)

I do not think the nineteenth century so far, not so different. […] Over the past 200 years, more things happened than between 1400 and 1600. […] The planet got smaller because of communication technology, for better and for worse. […] The nineteenth century, for being so close, is a rich context to be described and to criticize the current moment. What is science fiction? It’s to put into perspective our reality through the accentuation of problems and defects from that historical moment. (Brazilian steamer writer)

Freedom of expression […] It's a hobby to get away a little bit of our ordinary everyday, encouraging people to do something different. It’s for the pleasure [...] to meet different people, search new experiences. (Brazilian steamer)

Brazillian steamers’ strategies of visuality and sociality are acts of resistance to contemporary spatiotemporal compressions, providing an inter-space of temporality and hybrid culture, which combines different historical periods. However, steampunk hasn’t derived from a pure and simple import of Europeanised customs, which, in turn, would result in similar actions to the Brazilian Belle Époque. Neither has it intended to celebrate a tradition originated from English distant past of ladies and gentlemen.

Besides the fascination with the Victorian imaginary, what unites Brazilian steamers, no doubt, is the science fiction in its various products, questioning the inventions that marked the transition to the modern world, especially in science and technology. This identification is made clear in the narratives constructed individually and collectively by the steamers. Some seek to insert elements of history and Brazilian literature, as in the following example:

I tried to imagine how it would be a world in which the Baron [Mauá – Brazilian historical character] was even more influent, decisive to the directions of our country. So, I thought that the Abolitionist Campaign would be more successful with, let’s say, not only the prohibition of the slave trade in the 1850’s, but with the release of all slaves and with the attraction of foreign and specialized labor and, most importantly, a world in which there had not been the Paraguayan War, what would’ve stopped the waste of lives and money we had in reality. (Brazilian steamer writer)

The events that promote steampunk and encourage sociality among the participants are the main feature of the Brazilian group. Aiming to give visibility to their initiatives, steamers often attend events of other youth cultures, such as Victorian picnics (an event that has become a reference there). Each activity promoted by Steampunk Council of Paraná Lodge has a specific theme, in honor of historical characters and events, often from a specifically Brazilian context. They do not have a fixed schedule, but each event usually involves music, dance, literature and individual performances. The three major events promoted by Paraná steamers are named as the Steampunk Picnics, Steam Coffee (In Portuguese, Cafés a Vapor) and the workshops to learn how to customize clothing and objects.

The Steampunk Picnics are annual events held at parks in Curitiba, capital of Paraná state. The steamers enjoy the sunny Saturday or Sunday afternoons to do the “steampunk scene”, where they go dressed in their costumes, play games and participate on sweepstakes, gymkhanas and photographic sessions.

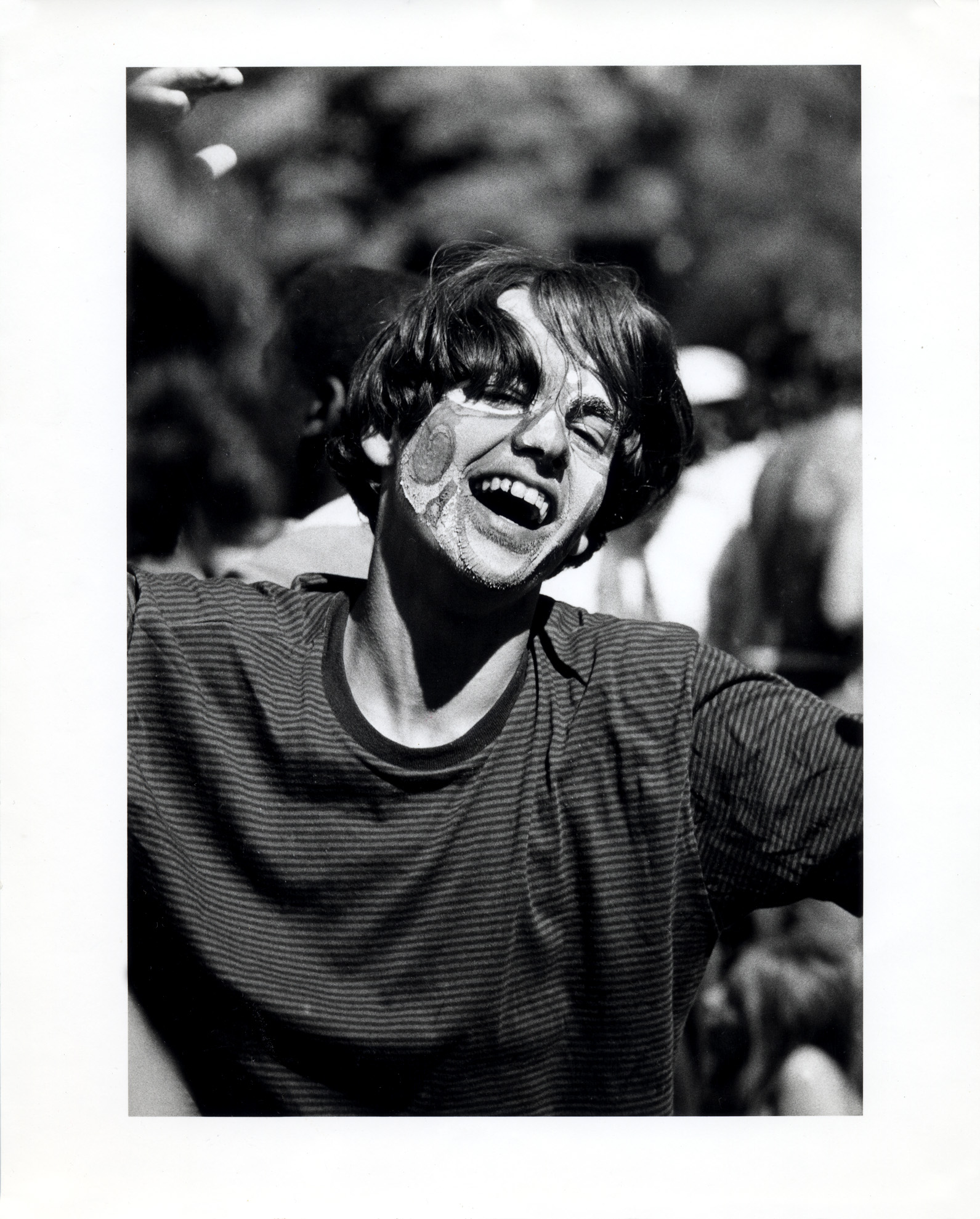

Convescote Steampunk, março de 2012. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil

Convescote Steampunk, março de 2012. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil

The customization workshops occur every two or three months (there is no strict regularity) in Curitiba. They are also used as a shop window for steamers to exhibit their artistic abilities. They are artisans, designers, stylists and photographers who take the opportunity to promote their work and, in some cases, sell them.

The customization workshops occur every two or three months (there is no strict regularity) in Curitiba. They are also used as a shop window for steamers to exhibit their artistic abilities. They are artisans, designers, stylists and photographers who take the opportunity to promote their work and, in some cases, sell them.

After posting on their blog (http://pr.steampunk.com.br/) and on the group's profile on Facebook (in Portuguese: Loja Paraná do Conselho Steampunk), the interested ones meet on a Saturday afternoon to learn basic techniques of steampunk styling. The workshops are taught by the older group members or by some guest who has a specific skill that can be useful in customizing clothing and accessories. During an afternoon, someone is highly unlikely to finish the process. But the steamers themselves make clear that the workshop will explain the basic technique. It is up to each person to develop (and even enhance) what was taught.

During workshops, Brazilian steamers discuss alternatives to materialize their imaginative ability

During workshops, Brazilian steamers discuss alternatives to materialize their imaginative ability

The workshops are characterized as a meaningful moment of sociality among the steamers, because there is sharing, exchange of ideas and interaction among them, while they discuss alternatives to materialize what they imagine. Tutors seek to encourage creativity by presenting a variety of objects made at home. The “students” identify themselves with these possibilities and discuss alternatives to adapt them to their purposes. Tutors share the difficulties to develop the techniques, aiming to ease the situation for those who are beginners.

Workshop to make mini and top hats

Workshop to make mini and top hats

Customizations are used in the practice of steamplay (adaptation of the term cosplay to the steampunk universe), when steamers perform their steampunk character, constructing their identities and embodying their clothing and accessories as well as their historical and social context. Public performances happen in the events that Steampunk Council of Paraná Lodge promotes or participates. Several factors influence the character creation, such as preferences and hobbies of each participant or their ability to afford the steamplay.

Steam Coffees are evening events. As an example, the night of Steam Coffee: The steampunk evolution (Tribute to Charles Darwin) began with the performance of a traditional tribal dance, created by two dancers for the event. According to one of them, the ethnic tribal dance joins elements and techniques of folk dances from around the world. The steampunk concept appears on the mix of industrial music and the aesthetic of the costumes.

Musical performance at Brazilian steampunk event

Musical performance at Brazilian steampunk event

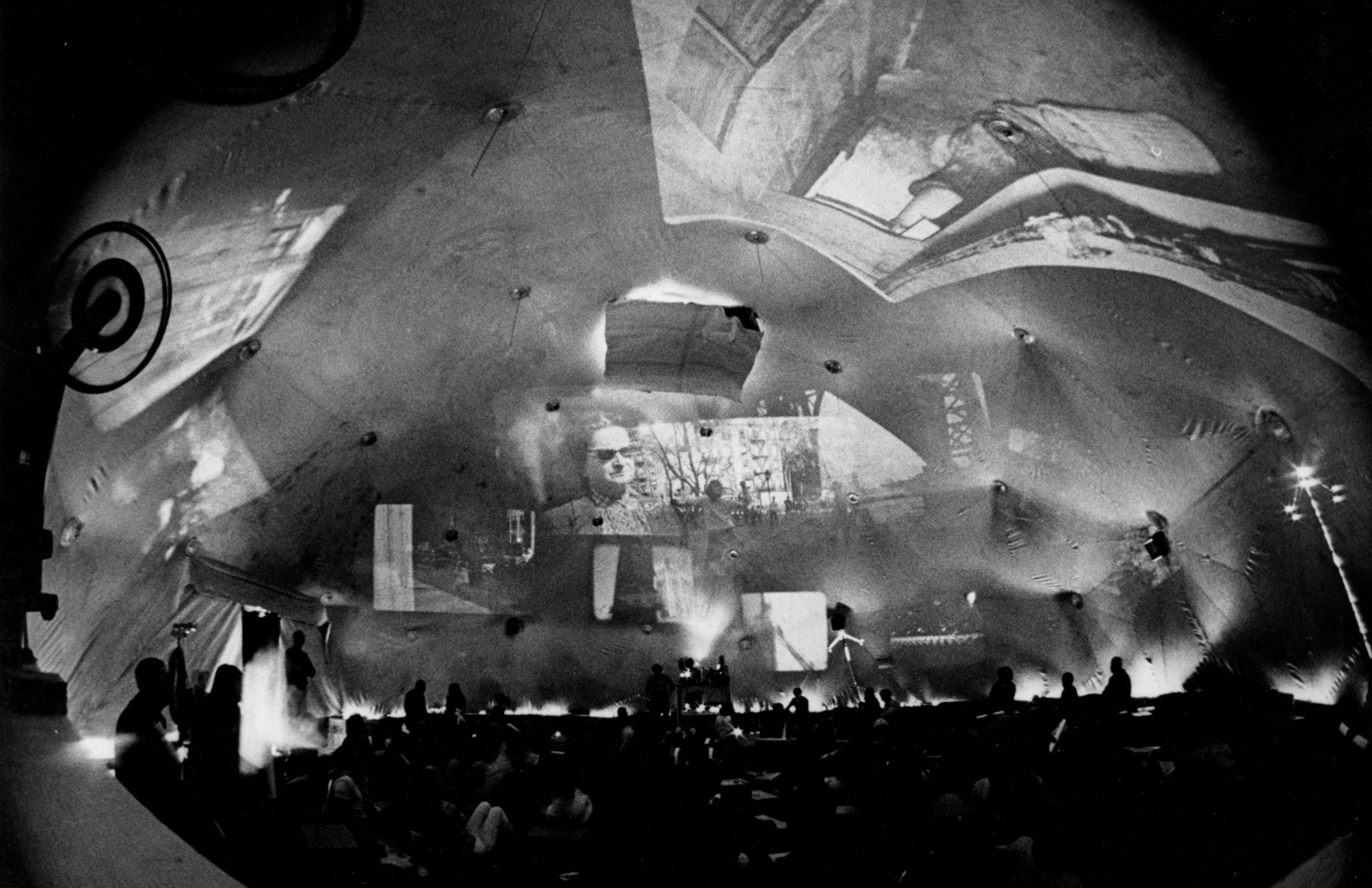

Steampunk event in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil

Steampunk event in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil

Performance of a traditional tribal dance, created to a Brazilian steampunk event

Performance of a traditional tribal dance, created to a Brazilian steampunk event

Participants of a Brazilian steampunk event

Participants of a Brazilian steampunk event

During the event, the participants had fun with a steampunk musical repertoire of a steamer DJ who shared music videos. Some steamers shared a steampunk tale written by one of the participants of Curitiba’s group, who is also a writer. Indeed, the practice of writing tales, editing magazines and creating all kind of steampunk media products (even if they’re not mainstream, but only released on the internet) is common among steamers. As pointed out by Jenkins (2010), these informal learning communities encourage participants to develop writing skills and styles as well as to build confidence in their own abilities before entering in the professional market.

Members of Steampunk Council of Paraná Lodge share a wide range of cultural interests drawn from the content of media culture products over which they claim a sense of ownership and mastery. Practices similar to those discussed by de Certeau (1998) and Jenkins (2010) in terms of bricolage or “poaching.” Steamers appropriate different science fiction books, movies, comics and RPG games, but giving them new meanings, expanding the stories, deepening their interpretations of the characters and reimagining the story world. The creations may even suggest impossible mixtures through the insertion of fictional or historical characters from different periods in the same narrative.

Similarly to what Jenkins (2010) describes, such practices involve a form of aesthetic perversion of the traditional limits imposed by the dominant cultural hierarchies which outline the desirable and undesirable cultures. Thus, they build a cultural and social identity through appropriation and modification of cultural products.

The first Brazilian steampunk photo roman – Curitiba’s steamers are pride to point out it as the first one – is a striking example. Steampunk Carnivale[1]photo roman (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ehm8RJ8KVwo) is a collective production involving performances by the various members of Steampunk Council of Paraná Lodge, who customized their costumes and accessories and collaborated to generate the plot. The work – which combined science ficton and intrigue -- was shared via Youtube.

Despite the understandable limitations of an amateur production, this photo roman can be characterized as contributing to an urban culture that has taken shape around a common interest in steampunk retrofuturism with the production and exchange of such products acting as part of what Thornton (1995) describes as a micromedia circuit. What matters here is not so much the aesthetic merits of the community’s productions or their comparison with more mainstream cultural products but rather the social and cultural dimensions of participants interactions with each other.

The cultural products that emerge from the steamers’ appropriation and remixing practices do not always fully cohere. Participants continually negotiate their relationship to the genre and to pre-existing culture materials according to their most immediate interests. As an example, note the following explanations of two steamers of Curitiba:

I really like gothic, so I wanted to make a gothic steamplay. I’ve brought a little bit of everything: I have keys, the belt that has potions, also weapons, which were made in the workshops. [ ... ] I’ve watched the movie The Crucible (and also read the book), and I’ve been writing the story for me. [...] Harry Potter has also influenced a little bit, so that my wand is from Harry Potter, it is not customized, I did not want to change it. (Brazilian steamer) One of my ideas is inspired by Assassin's Creed games, which there are murders [...] it is like a secret society, fighting against the old Knights Templar. (Brazilian steamer)

This is how steamers – between pirates and nomads (Jenkins, 2010) – create their performances and products in an experience that is both individual and collective, within a vast network of connections that constitute this participatory culture.

Brazilian steamer at Steam Coffee. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, 2012

Brazilian steamer at Steam Coffee. Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, 2012

Brazilian steamers

Brazilian steamers

Steamers start from the media culture products that most interest them and become producers of new texts including fictional narratives, photo romans, illustrations, photographic essays, customized objects, crafts, dance and music performances, fashion and accessories, magazines, events. These acts of cultural expression are informed by two competing logics: the Do It Yourself (DIY) aesthetic from the punk movement and the contemporary conception of Do It Together (DIT) as it has taken shape around the Maker movement. One emphasizes individual, the other collective production. Thus, even though DIY logic prevails, the premise is surrounded by a mutual aid policy: each steamer helps the others with his skills in making products and accessories, embodying the DIT logic of participatory culture.

This idea is summarized in the interview with one of the forerunners in Paraná, Carlos Alberto Machado:

People sometimes send e-mail asking: 'do you sell steampunk clothing?'. 'We are not selling, what we do is teach you how to do,' I say. [ ... ] Paraná is the state that is promoting more workshops. And the workshops are bringing a lot of people and a lot of good things. There is the shyest person who ends up getting more outgoing, and makes friends. [ ...] We do not call it as a class, the idea is not to teach you the 'abc'. The idea is to encourage the participants to bring things and the group teaches the group. [...] They bring this knowledge and show them what they do to encourage the participants to try to do something similar. (Brazilian steamer)

Thus, the interest in steampunk by Curitiba’s group is structured through the desire to interact and be part of a community that shares broader cultural and social interests. Sociality grows from mutual interests, reflecting the group’s particular interpretative conventions as they are shaped by individual and collective acts of story telling, performance, and cultural production. While there is a strong emphasis here on self-creation, we should recall that all of this activity occurs within a consumerist context, where critical interactions between man and technology coexist with leisure, hedonism, and consumption. Their retrofuturist imaginings emerge from a particular local context and get circulated through a micromedia circuit.

Brazilian steampunk reinserts questions that turn away from traditional political participation. Steampunk encourages its participants to return again and again to the core question: “what if had it been different?”. Besides, creating a story of an invented past is a way to discuss current and relevant issues. It’s not an attempt to return to past, not about engaging with an exotic foreignness, but an inter-space that mixes criticism, socio-temporal concern, hedonism, entertainment. More than the fascination for the historical period of Victorian Age itself, what prevails is the will of the steamers to recreate their own fictitious historical memory, which is strongly impacted by media culture.

Éverly Pegoraro is a Brazilian university lecturer and PhD candidate in Communication and Culture at State University of Midwestern Paraná, Brazil . His doctoral research deals with the relationship between visuality and sociality in steampunk. He is the leader of the Communication and Sociocultural Interfaces research group. Contact:everlyp@yahoo.com.br ou https://www.facebook.com/everly.pegoraro.

References

Bhabha, Homi (2011).O entrelugar das culturas. In: COUTINHO, Eduardo (Org.). O bazar global e o clube dos cavalheiros ingleses: textos seletos. [The global bazaar and the English gentlemen's club: selected texts].Rio de Janeiro: Rocco.

Certeau, Michel. de. (1998). A invenção do cotidiano. Artes de fazer [The practice of everyday life].(3rd ed.). Petrópolis, Brazil: Vozes. Conselho Steampunk. http://www.steampunk.com.br/.

Deleuze, Gilles; Guattari, Felix. (1995a). Mil Platôs. [Thousand Plateaus]. Vol. 1. São Paulo: Ed. 34. ______. Mil Platôs. (1995b). [Thousand Plateaus].Vol. 2. São Paulo: Ed. 34.

Jenkins, Henry. (2010). Piratas de textos.Fans, culturaparticipativa y televisión.[Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture]. Barcelona: Paidós.

Maffesoli, Michel. (1987). O tempo das tribos.O declínio do individualismo nas sociedades de massa. [The time of tribes.The decline of individualism in Mass Society]. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Forense—Universitária.

Thornton, Sarah. (1995). Club cultures: Music, media andsubcultural capital. Cambridge, England: Polity.

[1] Although the name of the photo roman refers to Carnival, one of Brazil's major festive periods, the theme has no direct reference to the subject. Curitiba is not known for its Carnival tradition. Besides, in the days of this festivity, there is an alternative event for those who do not enjoy Carnival: Zombie Walk. As the organizers of the event use to say: “in Curitiba, Carnival is a horror”.

Steampunk event in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil

Steampunk event in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil