From Media Matters to #blacklivesmatter: Black Hawk Hancock discusses John Fiske (Part Three)

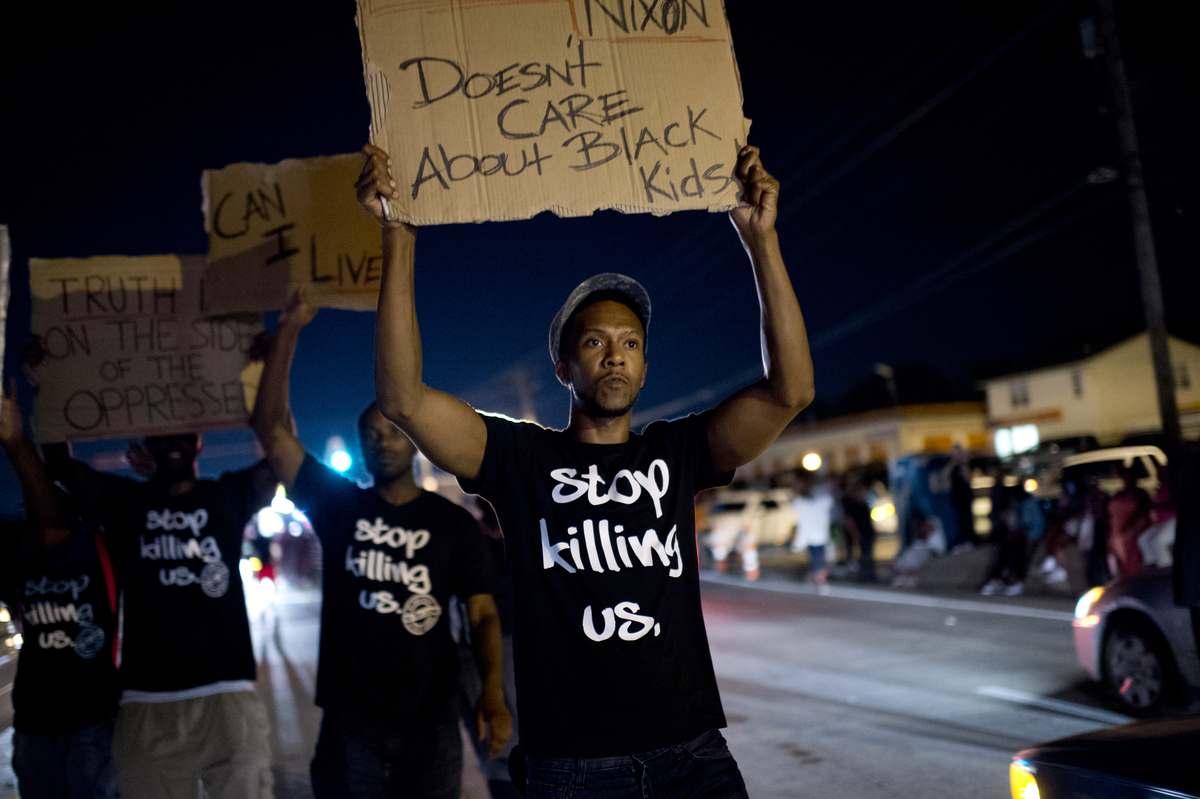

/In some ways, the Rodney King video set the stage for many subsequent debates about racialized police violence. Here, as now, the incident was caught on video and shown to the nation, yet then as now, the police faced no legal sanctions for their action and public outrage boiled over into the streets. What conceptual tools might Fiske’s account of these events contribute to the current debates around Ferguson, Baltimore, etc.?

I’d like to focus on the last part of the question, on the conceptual tools that can contribute to the current debates around Ferguson, Baltimore, etc. Before fully responding to this question, I should point out the other animating force behind the new introduction to Media Matters is what Berkeley Sociologist Michael Burawoy refers to as “public sociology,” whereby we as intellectuals intervene in the political debates and social problems of our time in the multiple publics or social spheres in society. [1] Public sociology takes on two dominant forms, the traditional public sociology, which disseminates information and attempts to stimulate debate in traditional media venues, such as popular trade press books, newspapers, magazines, and the organic public sociology that engages the particularistic interests of more circumscribed publics —community organizations, hospitals, schools, trade unions, etc. Public sociology, in either form, seeks to take information beyond any specific community and circulate it as widely as possible.

Fiske is doing a bit of both forms of public intellectual labor in Media Matters. I argue that what runs throughout Media Matters, and specifically captured in the excellent chapter on Black Liberation Radio, are the critical tools of constructing “counter-history” and ”counter-knowledge.” I find these to be of critical importance in our struggle for racial equality. These two approaches to documenting social life serve as correctives or alternatives to the official history and knowledge, or the history and knowledge that has been institutionalized by the dominant groups in society (the power-bloc) in order to create competing ways of interpreting the world as well as reposition and reinterpret the facts of the dominant knowledge. Counter-history assembles experiences and historical events in order to reveal the workings of power relations in society and how those power relations structure societies in inequalities. Counter-history illuminates the effects of those power relations upon bodies, revealing how those bodies have been subjugated, exploited, excluded, marginalized or silenced. In addition, counter-history reveals the social formations and social positions to which those bodies have been relegated. The focus on the body emphasizes how power relations are not simply conceptual, regulating the mind, but are also physical in that our socialization is also always embodied as well. Counter-history is the embodiment of past experiences that serve as a reservoir of knowledge that has been omitted from the official record. Counter-history gathers those past experiences and articulates them, connecting the past to the present, in effort to affect the present. Counter-history challenges the production and legitimacy of truth and knowledge by calling into question what official history erases, represses, denies or excludes. Counter-history is “effective” in that it is functional in giving articulation to a multiplicity of voices, understandings, and experiences that official history tries to silence in its homogeneity. Counter-history reveals the embodied experiences and truths of the disempowered that have been omitted from the official record. As such, it highlights the ways in which events, objects, statements, are never self-evident, but are always interpreted, articulated, and put into particular contexts. In doing so, the objectivity of official history, as the production of institutionalized knowledge, is undermined and shown to be the ideology of the dominant groups that govern society. Counter-history not only reveals alternative ways of knowing and subordinated experiences, it also illuminates the material, economic and technological disparities for circulating information between groups. Counter-history is never as strong as the dominant history, nor does it seek to replace the dominant history as the only truth of the world; rather counter-history works to be “effective” as it is constructed and operates to provide documentation and testimony to subjugated positions in society. As a result, the contestation between official history and counter-histories is one which always one that cuts across social, cultural, and political-economic realms of society.

The formation of knowledge or counter-knowledge, the ways that people understand themselves and their social relations, is always a matter of constructing a set of meanings. Since facts are never self-evident, knowledge is always a process of production in the interests of a group situated within a social system of power relations. Facts are resources that are linked together—articulated—within specific social contexts for particular ideologies, politics, and practices. This process requires a constant and ongoing articulation, disarticulation, and re-articulation of facts in the construction of knowledge. Since facts are always open to disarticulation and re-articulation, we can see how the classes that dominate social relations attempt to dominate the production of meaning/knowledge. Writing a counter-history/counter-knowledge requires “stealing” or the re-articulation of facts for the interests and effectiveness of a group’s social location. Groups that challenge those dominant meanings and rearticulate them in a counter-knowledge is what enables those groups to assert and attempt to preserve identities of their own self-definition and self-understanding.

By thinking about how constructing these alternatives are both intellectual and political endeavors, we can then start to think of strategic ways of deploying this information, as we forge alliances across different groups and publics who are invested in collective social change and social equality.

[1] Burawoy, Michael. 2005. “For Public Sociology.” American Sociological Review. 70(February): 4–28)

For Fiske, change in entertainment media and change in news media both help to shape the “structure of feeling” and the political climate of the country. As you note in your introduction, “According to Fiske, culture is always political.” So, the current debates around race are taking shape alongside struggles for more inclusion and diversity in the entertainment industry, not to mention real breakthroughs in terms of the representation of race -- From Scandal to Empire, from Fresh Off the Boat to Master of None. So, what tools does Fiske offer us for thinking about the interplay between news and entertainment?

https://youtu.be/qOno7HwiEPg

I think there are two parts to this line of questioning. First, the debates around race and diversity, and second the interplay between news and entertainment. As Fiske argued, culture is political, in that the production of meaning is always a contested site of social struggle through which the social order can be reproduced, but also questioned, critiqued, challenged, and changed. This is central to Fiske’s intellectual project of cultural critique.

The current debates around race and representation, both in terms of the ways that racial identities are portrayed and presented, and in terms of the sheer numbers of people of any particular group that are represented. So in this sense, I would see Fiske as pointing not just to the content of the performance, whether or not the character reinscribes some stereotype, but rather to the pressing political shift in terms of recognition. The Oscars were a breakthrough in terms of social and political pressure applied to the awards in a way that is unprecedented. Issues of diversity are not new, but the shift in our culture, such that they are now part and parcel of movie awards is front-page news and on the public agenda in a way I don’t think we have seen before. This defines something new, some shift in the “structure of feeling” in terms of how we as a society see ourselves and how the issue of diversity, in terms of recognition and validation, around the sheer numbers of people making cultural contributions can no longer be silenced or marginalized. Furthermore, the quality and popularity of minority dominated TV programs and films, also speaks to a shift in the fabric of society. To me this speaks to a new configuration of multiculturalism, a shift in terms of how we think of diversity on many levels of social life. I think this is very important for us to reflect on, given that when I was at Berkeley as an undergraduate in the early 1990s, multiculturalism, and the possibility of requiring a course of study on the topic was the political issue of the day.

There were strikes, sit-ins, protests, coming from both the left and the right, all over the possibility of having to take a course on multiculturalism. Now I teach courses on multiculturalism. It has become institutionalized. In fact my students today have grown up in an era where multiculturalism wasn’t something to be fought for, it is something that they take for granted (at least in terms of its rhetoric). In fact, I would argue that the issue of diversity and multiculturalism is one that is reconstituting the very social organization of society. Only through making multiculturalism central to both our thinking about society, and central to our politics, can we hope to gain any purchase on achieving social cohesion and reducing, if not eliminating, the mechanisms that structure societies in inequalities.

Second, as far as the ongoing interplay of news and entertainment, we have seen nothing but an ongoing erosion since the time of Media Matters. As Fiske argued, media have fundamentally changed our social relations in contemporary society, to the point where we can no longer rely on a “news” event vs. “entertainment” event distinction. When news and entertainment blur, distinctions of truth and false, real and unreal, objective and subjective distinctions become increasingly difficult to maintain. While I agree with Fiske that we cannot succumb to a pessimistic viewpoint that society has completely “imploded” into the “hyperreal” where the world is nothing but images, I do feel at times that we are getting closer and closer to that implosion. While I try and teach my students the forms of cultural literacy and cultural analysis that Fiske taught us, I see less and less “critical” in the ways those students interpret media and the ways they put those interpretations to use in everyday life. As a result, the analysis of media events, and the kind of cultural literacy and critical analysis Fiske advocated for, becomes ever more important in helping us negotiate these cultural shifts in society today.

Black Hawk Hancock is an Associate Professor of Sociology at DePaul University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin at Madison in Sociology, and his B.A. from the University of California at Berkeley in English and Philosophy. He is both an ethnographer whose work focuses on issues of race and culture, as well as a social theorist. His first ethnographic monograph, American Allegory: Lindy Hop and the Racial Imagination was published with The University of Chicago Press. His next book, In-Between Worlds: Mexican Kitchen Workers in Chicago’s Restaurant Industry, is currently under contract at The University of Chicago Press. His theoretical work includes two books with Roberta Garner, Social Theory: Continuities and Confrontations, 3rd edition (The University of Toronto Press), and Changing Theories: New Directions in Sociology (The University of Toronto Press), while his articles have appeared in such journals as The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, and History of the Human Sciences.