Global Fandom Jamboree Conversation: Mado Mai (Cameroon) and Anastasia Rossinskaya (Russia) (Part One)

/Mado Mai (M): I wondered where the common ground between us was. But it would appear I answered my own question when I saw you mentioned the youths, classrooms, communication, rejection and the social aspects of life.

Anastasia Rossinskaya (A): That is right, a lot of media nowadays is targeted at the youth. Much of it aims at communicating educational messages and bringing up social awareness in a way accessible and understandable for the youth, e.g. through TV shows and music. I would like to know more about your sociolinguistic studies of hip-hop and your findings in how it reflects this trend.

M: Thanks, Anastasia, for your curiosity on the sociolinguistic practices in Cameron. Indeed, most music and particularly the hip hop musical genre can be hardly understood without some sociolinguistic knowledge of the country. Concerning my interests, I specialize mostly in language and society - sociolinguistics. I am new to the world of fans and fandom. But, since this has to do with society, my hope is that together we shall be able to consider the intersection of hip hop language use, fandom and popular culture. If possible, see how this can impact communication. Of course, you will see much of Cameroon language styles and practices through our interactions.

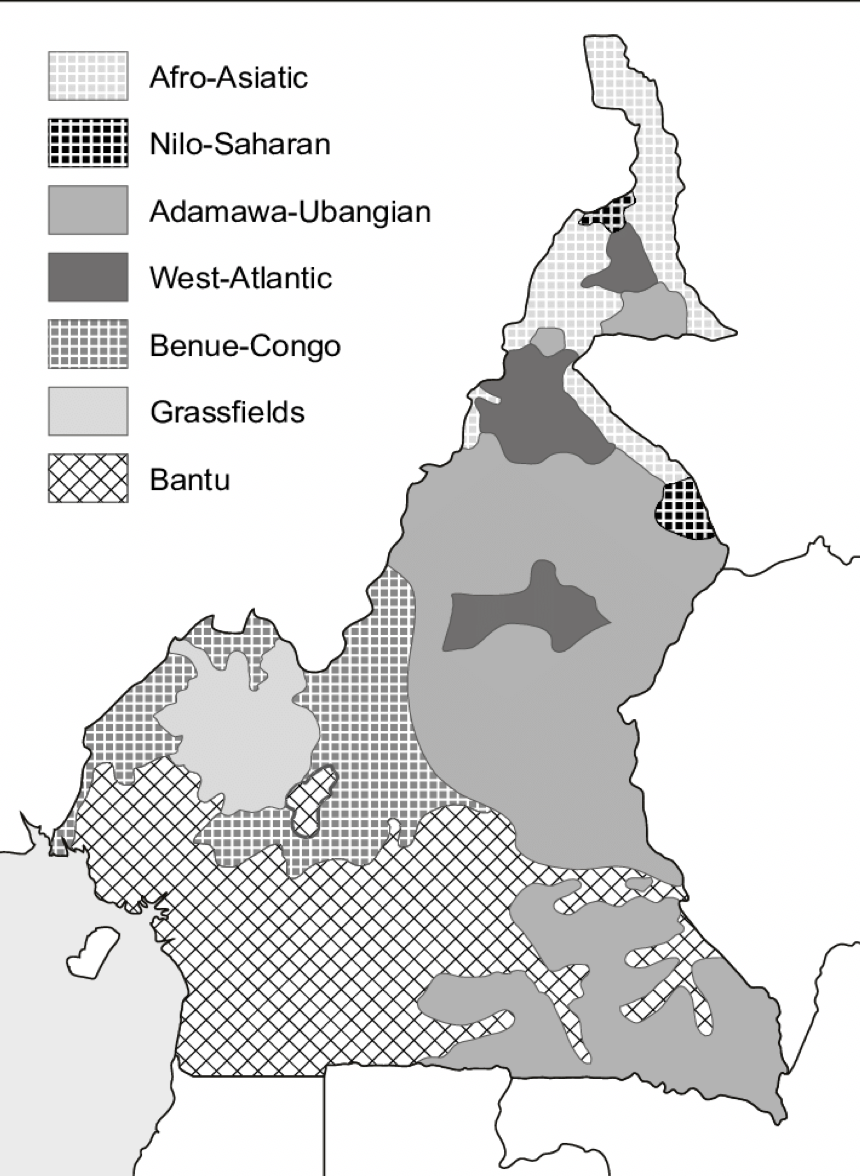

From a linguistic viewpoint, reports from Ethnologue (2002) show there are 279 national languages in Cameroon, a country as small as San Francisco. This country also has a complex sociolinguistic background with a resultant linguistic baggage that relegates the national languages to the background while encouraging an official language bilingualism of colonial language – English and French.

Stanley Ebai Enow is an embodiment of this complexity. He is a Cameroonian rapper, radio and TV presenter, and voice actor who co-owns the record label, Motherland Empire. He is popularly known as Bayangi boy, with Bayangi being a linguistic group in the South West region of Cameroon- the birthplace of his parents. Why I prefer him as an example of a Cameroonian hip hop artist is not only due to his growing popularity as a multiple award winner with more than one million followers on YouTube at the release of his song Hein Père (where ehein is a national slang expressing surprise and père means father in French) but also because Stanley Ebai Enow is a representation of Cameroon in terms of cultural, linguistic, geographic and socio-economic diversity. His socio-cultural background, choice of music genre and language form which he uses for communication with his fans, followers and audiences portrays both uniqueness and heterogeneity that is tantamount to what some historians and geographers often refer to as “Africa in miniature” when they try to highlight the fact that the diversity found in Cameroon alone encompasses the entire African continent.

Besides this, popular culture, and its constituents have apparently not been attractive to the Cameroonian academia. This is especially true if one has to compare it to the number of theses already emerging on fandom from the Russian institutions of higher education which my conversational partner, Anastasia still considers small. In fact, when it comes to Cameroon, there are few accounts on popular culture (see for example Tagem 2016, Mbock 1996, Nyamjoh, 1996) with nothing concrete on hip hop. All three authors link music to politics and place of origin. In the process, they also emphasise the diversity of music, culture and identity without failing to point out the critical undertone of the artists. Tagem (2016), especially situates popular culture as an aspect of oral history and collective memory while showcasing the use of Camfranglais, Cameroon Pidgin English and of course the multilingual and multicultural diversity of the country. Most artists in Cameroon draw from either Cameroon Pidgin English (CPE - an English based pidgin, arguably a creole, formed by borrowing from English and some of the many national languages, which also plays the role of mother tongue for a majority of urban youths in Cameroon) or from Camfranglais (a mixture of French, English and some national language expressions) and sometimes both as is the case with Stanley Enow when he displays his multicultural and multilingual diversity during the AFCON opening ceremony (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvBJLJuVn5k) in both song and dance in ways that effectively communicate, entertain and educate the audiences from all walks of life and among all age groups. Linguistic diversity in Cameroonian society is an aged long phenomenon. For this reason, the types of music in Cameroon are not only numerous but also diverse in nature. The many different types of music in modern society each represents unique experiences that shape identity. In Cameroon for instance, makossa, bikusi, bottle dance and bend skin among others, usually relate to celebration and happiness in general where themes such as love, social problems are dominant.

This notwithstanding, many have decried the fact that local rhythms are now so transformed that elders don not recognize anything anymore. Local artists have also been accused of copying international artists when it comes to dressing styles, which result in outfits that are considered ‘shameless’. Accordingly, one talent agent and producer Florence Tity-Dimbeng, asserts that the Cameroonian music lacks identity and has become senseless. However, an art critic Théodore Kayese suggests that the evolution of music can be seen from a different angle and that to get a real opinion about popular evolution, one has to look separately at every single angle of Cameroon. Over the last 10 years, each part of the country, he reckons, has had its hour of glory, for example; the coast with makossa, the western part with ben-skin, the north west with njang and samba, the centre, east and south with Bikutsi. Only the north didn’t really have a specific style although, no successful musical festival can take place without representation from the north. Of all these rhythms, is the afro-fusion and particularly hip-hip, which is very popular among youths thanks to artists like Krotal, Gasha, Stanley Enow, X-Maleya, Tizeu No Name Crew and Jovi One Love among others. This young generation of artists is definitely ready to take off.

From this perspective, it can be said that the hip hop culture in modern society can draw together various people from many different backgrounds. The hip hop culture as Harris (2019) argues is more than just a culture. It is a phenomenon. This phenomenon is now explored by youths and artists, particularly the hip hop artists to capture a kind of globalized sociolinguistics reality among young people where multilingualism is presented as both stylish and mobile. Hip hop according to (Nyamjoh 1999 and Mbock 1996) is a genre traditionally associated with resistance, an aspect which coincidentally relates to the Russians’ popular views on fandom as Anastasia had mentioned in one of our conversations.

Following from the multicultural and multilingual landscape of Cameroon, I sought for a scholarship that recognizes the intermixing of various Cameroonian languages and language forms in hip hop, what Agha (2007) has called amalgam systems, first to initiate a communicative mode that would bring to fore the creative and stylistic realities of a heterogeneous urban Cameroonian youths, and second, to inductee popular culture research in the area of hip hop into the Cameroonian academia as it is already an inundated area of research around the globe.

A: Thank you for this abundant tour into Cameroonian hip-hop culture and the state of its research. Many trends are similar to the Russian music scene, especially the accusations of copying foreign artists. On the other hand, various language and ethnic backgrounds of our multicultural and multilingual country are heavily underrepresented on the stage, which is dominated by the Russian language, only one of more than 150 languages of Russia (according to the Languages of Russia project http://jazykirf.iling-ran.ru/list_concept2020.shtml).

M: In your opening statement you point out that participating in fandom activities can have educational effects. Have you had a chance to research it and find out what these effects are, particularly in the sphere of communication?

A: Thank you for your question. I am happy to have this opportunity to share the results of my latest research. When I got interested in studying media and fandom I decided to look at them from the point of view most natural for me as a scholar, i.e. through an educational lens. We should keep in mind that education is not limited to classrooms. We learn a lot outside of the formal school system: in everyday life, traveling to and back from work or place of study, while enjoying hobbies and arts, doing social and volunteer work, etc. It is particularly important to consider in Russia, where school education is still quite conservative and uses approaches developed more than a hundred years ago, e.g. limited opportunities for teamwork, initiative, and creativity. Furthermore, the cult of mistakes and punishment for them instead of learning from them and the authoritarian role of a teacher doesn't allow to successfully implement teaching 21st-century skills in schools. Therefore, I focus my research on how these skills are developed outside school and which activities are more effective in compensating for the lack of attention to them in formal educational system.

As an example, I would like to share some results of my recent research of DRUCK fandom activities. DRUCK (Ger. pressure) is a German youth TV show produced by funk TV channel. It is a remake of the legendary SKAM, mentioned in some of the previous conversations. DRUCK has seven seasons so far. The eighth has been recently announced for spring 2022. The first four seasons were based on SKAM characters and plotlines, after that the new generation was introduced (Pic 1). DRUCK fandom is quite big for a local non-English language show and includes people of various age groups from Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, the USA, Poland, the UK, Switzerland, Russia, France, Italy, Spain, Korea, and other countries.

Pic 1. Old (left) and new generations of DRUCK. Official promo materials from funk TV channel.

The aim of my recent research was to determine the educational outcomes of fanfiction writing in DRUCK fandom. In March 2022 it had 1454 works posted on Archive of Our Own site. In January 2022 I held a series of interviews with ten ficwriters from DRUCK fandom. They helped me to compile a list of educational results of their ficwritng activities. Communication skills are quite significant among them.

Writers who work in pairs or groups learn to effectively communicate with each other to get to the mutually satisfactory result of their collaboration – a posted fanfic. Communication skills that they require for it include abilities to state one’s opinion clearly, support it with valid arguments, listen to and consider opposite opinions, discuss and come to decisions together. We see here that communication skills develop along with such collaboration skills as the ability to plan work together, to support and motivate each other to write.

On the other hand, interviews showed that writing fanfiction for those who work alone can also be considered a communicative practice because they enjoy interacting with readers, discussing their work, responding to requests, and sometimes discussing personal issues or problems raised by their works of fanfiction.

These interviews also gave me an interesting input on the motivation that drives ficwriters. Some of my respondents mentioned that they started writing because they wanted to communicate about their favorite media – DRUCK. Communication between ficwriters and readers happens mostly on the platforms where fanfiction is posted. My respondents admitted that lack of communication discourages them. Some reported that they stopped posting or writing for the fandom at all because they didn’t receive enough communicative support from the readers. Many respondents compared different platforms where they publish their works in terms of intensity of communication. They often complained that though Archive of Our Own is the most populous platform now, it provides much fewer means for communication between writers and readers than others before, e.g. LiveJournal, and therefore ficwriters are not satisfied with the amount and quality of communication there.

Writer-readers communication also contributes to the development of their communication skills such as the ability to listen and read, to respond regarding the other person’s personality and life circumstances, and to maintain prolonged communication. One respondent, who focuses much of their writing on exploring communication disorders and disruptions, noted that writing fanfiction about characters dealing with communication problems helped them to feel more confident when communicating in their everyday life.