The Problem with the "Main Character" Meme

/This is the third in a series of blog posts written by students in my Public Intellectuals: Theory and Practice seminar.

Alexandria Arrieta

The Problem with the “Main Character” Meme

On May 26, a TikTok user named Ashley Ward posted a video of herself lying on a towel at the beach with this voiceover:

You have to start romanticizing your life. You have to start thinking of yourself as the main character because if you don’t, life will continue to pass you by and all the little things that make it so beautiful will continue to go unnoticed. So take a second, and look around, and realize that it is a blessing to be here right now.

Main character video by Ashley Ward posted on May 26

It is a pretty simple, even trite idea, but being the “main character” in life is something that feels particularly resonant right now for teenagers and young adults who are missing out on some of the basic milestones of growing up, such as prom, graduation, and fooling around with friends. They may feel as though their agency and their youth have been taken away as they are forced to awkwardly navigate many of those experiences through Zoom or worse, alongside their parents. As a result, users like Ward started to create content about what it means to be the “main character” in May. Many latched onto Ward’s audio and used it to soundtrack TikTok videos of themselves and their friends going on camping trips, running on beaches during sunset, driving late at night and (of course) editing them with retro film filters. Beyond that, a whole “main character” discourse emerged over the summer on TikTok through various types of memes and comments, and it actually reveals a lot about the ways in which teens are modeled what it means to “come of age” through media, and specifically, through whiteness.

Over the past decade, both major studio films like The Fault in Our Stars (2014) and Love, Simon (2018) and critically acclaimed indie pieces like Lady Bird (2018), Boyhood (2014), Booksmart (2019), and Call Me By Your Name (2017) have presented coming of age narratives focused on white protagonists navigating identity, sexuality and purpose in the transition from adolescence into adulthood.

Amanda Mary Anna in her YouTube video "dressing like the main character in a coming of age movie" posted on July 16

These films, especially those made by indie production companies like A24, provided key references as the main character meme spread on TikTok, YouTube and Spotify over the summer.

Emma Topp in her YouTube video "HOW TO ROMANTICIZE YOUR LIFE || main character energy" posted on August 18

In her YouTube video entitled “becoming the main character of your life,” Claire Bergen explains, “You basically just need to essentially live your life as if you are a character in a movie or a tv show or a book because everyone’s always jealous of the lives of these characters but you can literally have that life if you wish to and I believe that to my core. It’s important to do things for yourself, do things that feed your soul, do what you want to when you want to.” She then proceeds to reference the show Outer Banksas a model of adventurous risk-taking. Many of these main character videos on YouTube begin with a general explanation of the concept and proceed to model “main character energy” through a makeup and outfit tutorial, drawing from the costume design of specific coming of age films as references. It is in these moments where the meme seems to intersect the most with activities of tv and film fandom through casual cosplay. But other than that, much of the discourse involves a general pop cultural engagement with narrative studies and understanding of character.

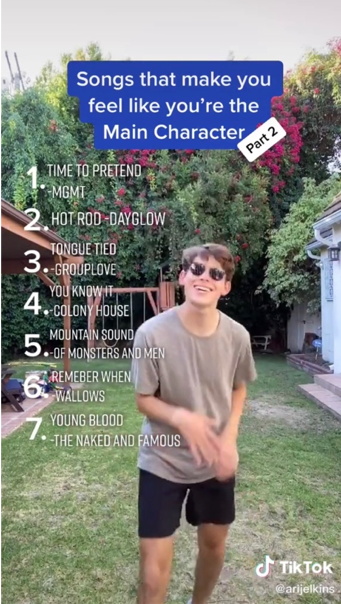

TikTok video posted by @arijelkins on July 6

Perhaps the most important reference that teens have drawn from these coming of age films is the particular sonic landscapes they present through soundtracks full of artists from indie and alt rock genres. Early in the development of this main character meme on TikTok, users started to make videos about the songs that make them feel like main characters, and many of them used bands that often appear in these films, such as M83 and Grouplove. There is even a growing number of playlists on Spotify and YouTube called “main character” that are dominated by white artists and bands, such as Lorde, Wallows, COIN, and Dayglow—acts that have situated many of their music videos in suburban streets and neighborhoods. These playlists often have thousands of followers, and one of them “main. character.” by David Welch (which I found out about on TikTok) has almost 100,000 followers. There are a few artists of color that I’ve noticed on these playlists, such as Labrinth (who made the soundtrack for Euphoria) and Frank Ocean, but it’s important to note that genres like hip-hop are largely absent from these playlists and are not part of this particular sonic landscape for coming of age.

Spotify curators created a popular main character playlist that has over 100,000 followers featuring primarily indie and alt rock music bands and artists

As a researcher who studies the relationship between Internet memes and popular music, I was initially interested in this particular meme because instead of merely propelling individual songs into virality (as TikTok often does), the main character meme has resulted in imaginative worldbuilding through playlist curation. As I was sifting through playlists, I also remembered that about a year ago my friend Brandon, a nineteen year old that I know through volunteering, suggested that I follow his Spotify playlist “Life’s an Indie Film, Vol. I,” which featured a lot of the same songs that were highlighted this year through the main character meme. When I asked him why he made his playlist, he said, “It’s just songs I loved that matched me and who I was in those moments when I was going through something or doing something like sneaking out late at night with friends [...] almost like a time capsule.” He also explained that he became annoyed when this type of playlisting became part of the main character meme because it felt like it had lost its meaning.

Wallows is an alt rock band that often appears on main character playlists

But it seems that a key difference between the way in which Brandon and others engaged in playlisting indie film music in 2018 and 2019 and how it played out this year is that while Brandon was working to capture memories from his teen years, many TikTokers were attempting to create memories that they never got to experience due to COVID-19. The main character idea was not simply focused on nostalgic reflection mediated through film references, but instead, became a call to reassert agency over a year of lost experiences. As platforms like TikTok increasingly center content creation around a matching process between video and audio, young users are becoming particularly fluent in soundtracking. At times, it feels as if the Internet has raised the next generation of skilled music supervisors, and at other moments, it seems as if they are simply reiterating past creative choices and tropes from popular films—even as these films reify racial stereotypes and lack of representation.

As TikTokers started to create videos about the qualifications for being the main character, such as childhood trauma and having parents that are divorced, user @nabazillion created a video that highlighted that whiteness seems to be a central characteristic.

TikTok video posted by @nabazillion on May 25

Though some users in the comments celebrated the fact that they were not eliminated from qualifying as main characters, others recognized that @nabazillion’s video was actually a commentary about lack of representation in the coming of age genre. It’s a severe issue—only 34.3 percent of speaking roles in the top 100 films of 2019 were given to people of color (Smith et al, 2020, p. 2)—and it’s also something that prior generations of people of color have had to navigate in different ways. In their editorial piece that calls readers to rethink the politics of representation by “looking away” from whiteness, J. Reid Miller, Richard T. Rodríguez, Celine Parreñas Shimizu (2018) write, “Thinking about the 1980s movies of our American teenhood, we recognize how we were forced to be white in our spectatorships and fantasies—you have to be white to be in this!” (p. 240).

In her YouTube video, Amanda Mary Anna, a NYU film student, says, “When I think about the main character what comes to mind is the quirky, skinny, white ingénue in a low budget coming of age film set in suburbia, not McMansions and strip malls suburbia but like cute, quaint houses and like sunflower fields suburbia, you know what I’m talking about.” After declaring that she is “here to be the black Lady Bird,” she provides a tutorial on how to dress and model the adventurous and free-spirited behavior of the character. Both Amanda Mary Anna and users in the comments expressed the desire for more coming of age films featuring black protagonists that are not set in inner-city contexts or focused on racial trauma:

The first comment is interesting not simply because it’s an expression of a desire for black coming of age stories set in suburban spaces, but also because a suburban setting feels like a particular prerequisite for entry into this genre. It is also important to note that films like The Hate U Give (2018), which features a black adolescent protagonist dealing with racial violence and police brutality, were not commonly referenced in this meme because they did not function as compelling sites of escapism. It’s not that coming of age films about people of color don’t exist—they are beginning to become more common, especially with newer Netflix originals like Never Have I Ever (2020) or To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before (2018)— but the meme tended to circulate a particular, narrow vision of adolescence modeled by films in which white protagonists don’t need to worry about the daily reality of systemic racism but are able to explore other aspects of identity formation.

This year, as police brutality against black lives has reached a critical boiling point and COVID-19 has revealed entrenched socioeconomic inequality along racial lines as Latinx and black communities have been disproportionately impacted by the virus, it is important to consider how this genre of film has too often reinforced “coming of age” as a privilege of whiteness. And by this I’m not simply referring to growing up, but rather, the privilege of having the space to engage in exploration, rebellion and play in the process with little ramifications. Related to this is the way in which suburban spaces have been imagined and invoked within political discourse this year. On one hand, President Donald Trump has made incessant appeals to his white voter base by stoking fear that the suburbs are at risk due to the encroachment of low-income housing and Obama-era policies bent on breaking down suburban racial segregation. On the other, when Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was asked in July what cities would look like if the police were to be defunded, her response was that they would look like a suburb. The way that we conceptualize cities and invoke the imagery of the suburb, beyond existing as a bastion of white flight and racial segregation, has a significant impact on civic imagination and spatial figurations of community.

The “main character” meme has grown and developed in some interesting ways within the last month or so. Many TikTok users have taken to the comment sections of comedic videos to identify “main character energy” when someone in a video behaves with freedom and an extreme lack of self-consciousness about what others think and have applied the term much more liberally to individuals from different generations. Others made fun of the trite nature of Olivia Ward’s audio by using it in videos of animals defecating.

TikTok video posted by @eshelton3 on August 14

The song “Heather” by Conan Gray became a sleeper hit as it captured the particular despair of being a side character. In the song, Gray writes about how the person he is in love with is in love with Heather, a seemingly perfect girl that everyone is jealous of. The song has inspired the creation of over a million videos, and in many of them, teens identify the “heathers” of their families and their schools or post vintage photos of their moms who they believe were the “heathers” of their time.

Much of the research I have done in the past has focused on how music memes can work to dismantle racialized genre borders in the music industry, but this is an example of the opposite. Memes, as digital items that can be rapidly spread or imitated, have the potential to quickly reinforce these borders as well, especially when they are not created in a comedic mode or for the purposes of trolling. As teens grappled with and mourned the experiences that they missed out on this year, they largely perpetuated narrow representations in pop culture of what those moments should entail through the main character meme. In the process, they often worked to reify “coming of age” as a process that is intertwined with systems of race and privilege.

References:

Reid Miller, J., Rodríguez, R. T., & Shimizu, C. P. (2018). The Unwatchability of Whiteness: A New Imperative of Representation. Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas, 4(3), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1163/23523085-00403001

Smith, D. S. L., & Pieper, D. K. (2020). Inequality in 1,300 Popular Films: xamining Portrayals of Gender, Race/Ethnicity, LGBTQ & Disability from 2007 to 2019. USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, 42.

Alexandria Arrieta is a doctoral student in Communication at the University of Southern California. She researches the relationship between popular music and Internet memes and also focuses on issues related to gender and race in the music industry. Arrieta is an independent music artist and producer who has toured across the west coast.