In Search of Indian Comics (Part One): Folk Roots and Traditions

/So far, my account of my trip to India this summer has centered on time spent in Mumbai (which was our home base) and its surrounding cities. I want to return to my travel narrative over the next few posts -- first focusing on Delhi and later on some of the other cities in India we visited. My time in Delhi was especially preoccupied with trying to understand the current state of comics and graphic novels in India, given that many key artists and authors are based in that city. I am going to use the next few posts to share what I learned. Parmesh Shahani from the Godrej Indian Culture Lab, my host, had arranged for a meeting at the Crafts Museum for lunch with a mix of some of the country’s top creators of graphic novels. The Museum itself is a great institution. It showcases living crafts traditions from across the country. The museum is open air: you walk around and look at, for example, a massive display of terra cotta sculptures, wall paintings and carvings representing different traditions, and stalls where craftspeople are producing and selling their work. The Crafts Museum proved to be the ideal location for this gathering, since it allowed me to place contemporary graphic practices in India in the context of a much larger tradition of pictographic wall art from various local cultures.

The following are some examples of what these wall paintings look like: it is not hard to find here forms of local practice that display principles of juxtaposition and sequence, stylization and expression, and simplification and exaggeration, that could provide the cornerstones for more contemporary forms of cartooning, and indeed, as we will see, some contemporary artists are beginning to build upon these practices to create distinctive kinds of graphic practices. The mural below represents a Muriya painting from Bastar, Chhatisgarh.

Below, in red, are figures drawn by Warli artists, who come from Maharashtra.

Below is a mural representing the traditions of Patachitra artists from Odisha, which is striking because of its use of panel boxes, unlike almost all of the other folk art styles we saw.

And these are Gond paintings from Madhiya Pradesh.

Below are some of my impressions of a contemporary graphic novel, Bhimayana: Incidents in the Life of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, which was inspired by Gond art.The story was written by Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand and illustrated by Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam. Ambedkar was an important spokesman for the rights of the Dalits (or "Untouchables"), and this book deals with the politics of the caste system in India, attempting to bridge from historic events and struggles in the early 20th century with some of the still horrible conditions and prejudices confronting the Dalits today. As an American, I had a high school geography class level understanding of the caste system, but this was a really powerful account of how caste worked on the level of basic human needs, especially focusing on access to water and shelter, and it was chilling to read accounts of very recent incidents of violence directed against the Dalits by upper caste Indians, when they crossed informal lines about whether or not they can draw water from a particular pond, even though they had been granted basic human rights some decades before. Ambedkar sounds like a remarkable political leader, who the comic suggests has often been left out of many contemporary accounts of the country’s history, except insofar as he is credited with helping to write the nation’s constitution upon its independence from Great Britain.

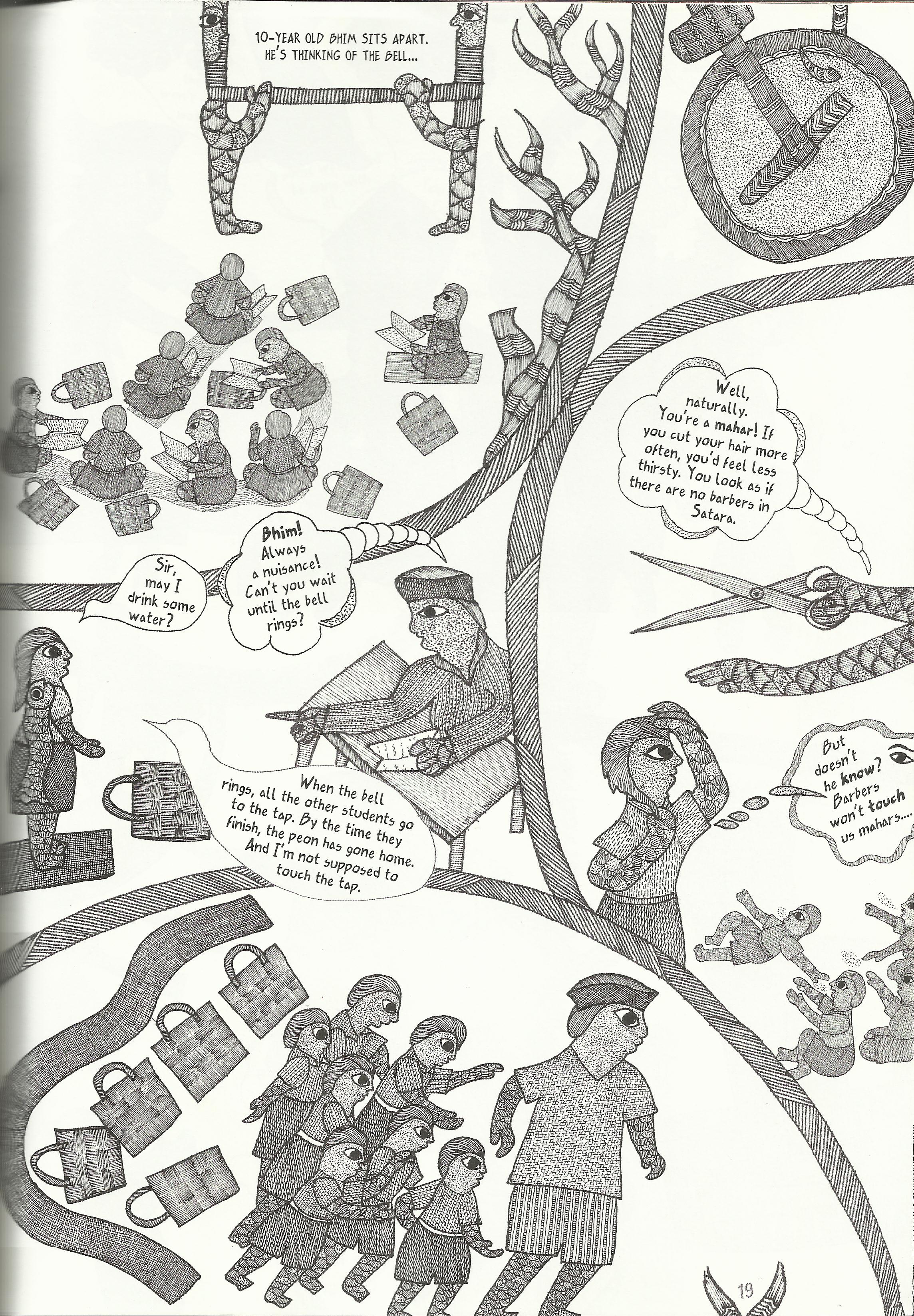

As powerful as the content of the graphic novel is, what really blew me away was the visual style: it is unlike any comic I have ever read before (and that’s increasingly difficult to accomplish). The artists are Gonds, that is members of a tribal community in Central India, which maintain a very traditional culture, and have developed their own art style known as Digna. According to the explanation in the back of the book, the artists had never encountered graphic novels before and found some aspects of the form philosophically troublesome: “We’d like to state one thing very clearly at the outset. We will not force our characters into boxes. It stifles them. We prefer to mount our work in open spaces. Our art is Khulla (open) where there’s space for all to breathe.” We can understand this position better looking at the example above and this one below of their traditional wall art, where there are no formal boundaries between figures. And when you see these huge, intricately entangled, wall paintings, you get a fuller sense of how they have had to reimagine this style for the printed page.

An account of their art in the back of the graphic novel explains, "Tiresome photorealism was out of the question. Nor would the Vyams [Traditional bards and artists] offer cinematic establishment shots, close-ups or extreme close-ups (of tense hands, surprised eyes, furrowed brow), mid-shot, perspective, light and shadow, three dimensionality, aerial views, low angles, etc., that have come to constitute the muse-en-scene of graphic books. The same character might not appear similar throughout the book."

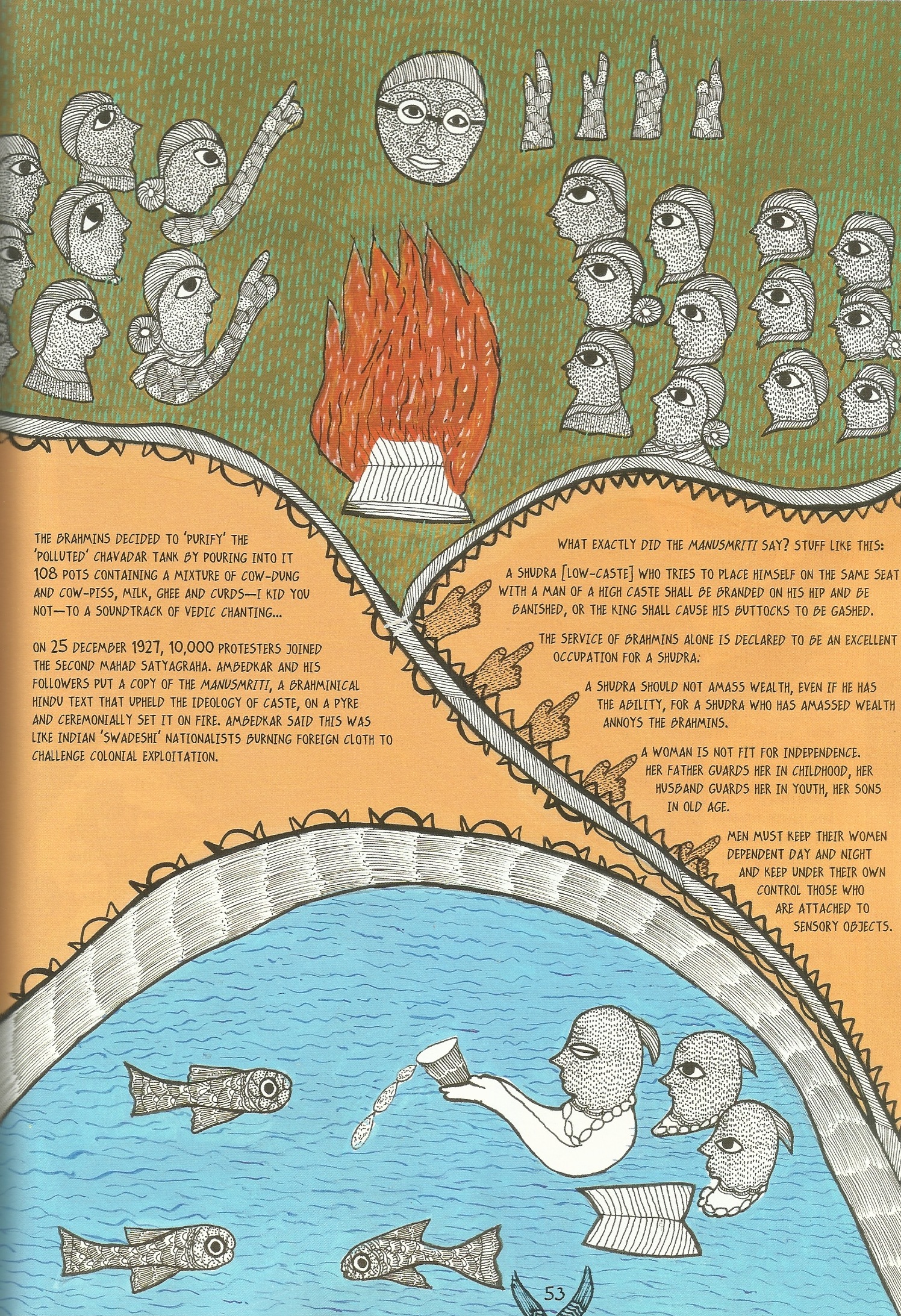

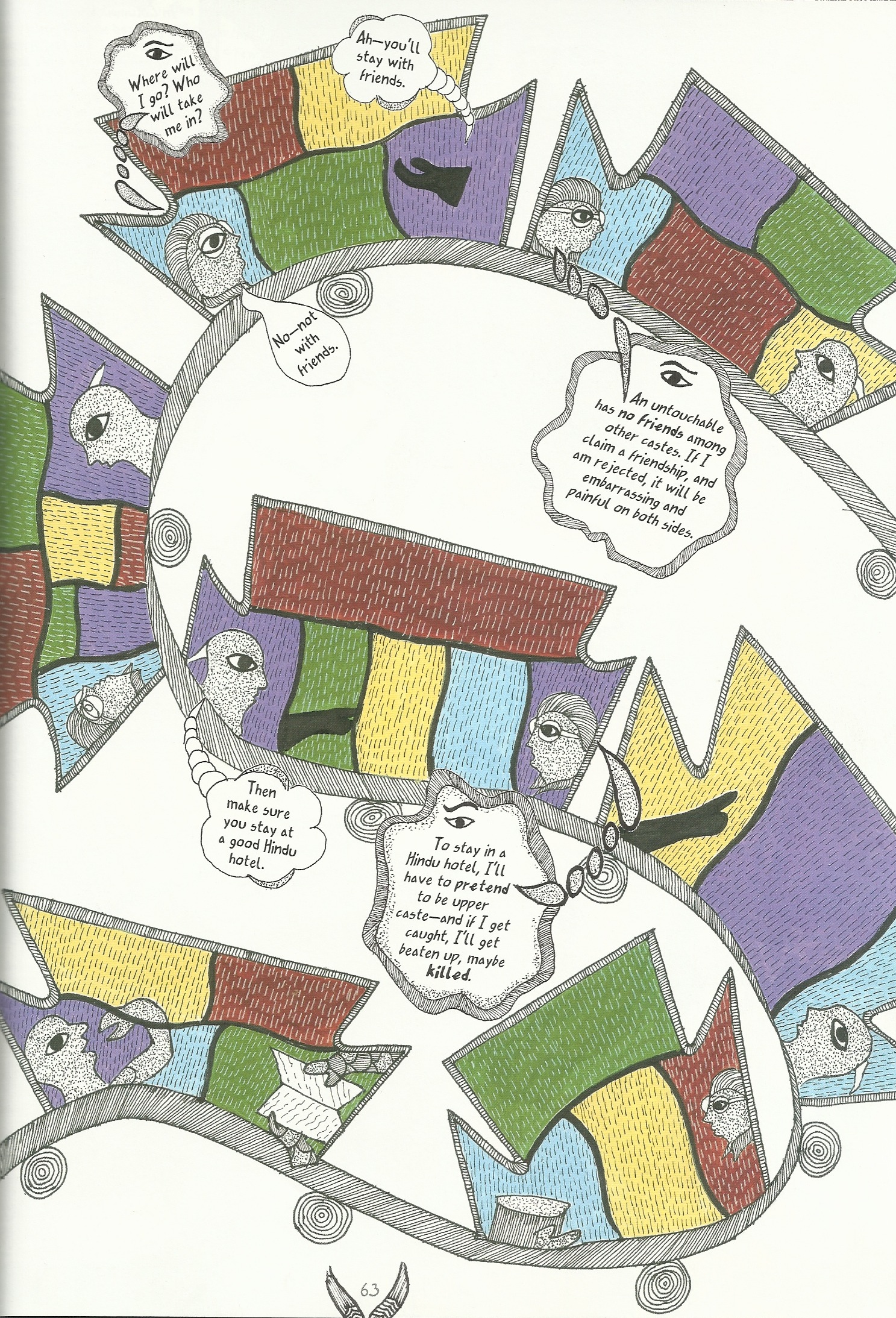

Below are a few examples of the pages from Bhimayana, showing the ways the artists organize the page, beyond traditional grids, boxes, panels, and gutters.

Here they use blocks of texts to separate out two opposing groups of characters and hint at the segregation created by the caste system.

And from there, they decided to draw more on their tribe’s visual traditions, which include the use of different kinds of word balloons to symbolize the character’s moral philosophies often through analogy to different animal forms. The result is stunning, forcing you to rethink so many of the ways that comics in the U.S. functions as, in Scott McCloud’s terms, “an invisible art” because it relies so heavily on shared visual conventions.

For example, in the panel below, speech bubbles take the shape of birds, and appear "only for characters whose speech is soft, the lovable characters, the victims of caste -- men and women who speak like birds."

Some of the word balloons below have stingers and are "full of words that carry a sting. Characters who love caste, whose words contain poison, whose touch is venomous."

In addition, you see a third kind of balloon here -- one which depicts thoughts that occur within "the mind's eye" -- "words that cannot be heard but can be perceived."

You can also see throughout the book the use of traditional forms of representation to depict more contemporary settings, so this image depicts the characters on a railroad train.

Here's a link to a review of the graphic novel which appeared in Comics Journal. Like most of the books I discuss throughout this series of posts, it is written in English and is available through Amazon and other online bookstores, but does not seem to have penetrated very far into the comic shops of the United States. Part of my goal in writing this series is to call attention to work that has largely passed unnoticed by American comics fans.

MARG: A Magazine of the Arts devoted its December 2014 issue to "Comics in India." I was struck by a series of images by Manjula Padmanabhan, who attempts to represent popular western comics characters, including Calvin and Hobbes, Archie and Veronica, Garfield,and Modesty Blaze, through the traditional language of Mithila paintings. As the artist explained, "I found it quite liberating to use a different standard of aesthetics to create these drawings, such as the checkered borders used for separating one scene from the next."

This special issue includes a rather interesting discussion of the ways Indian comics are building on traditional arts practices, written by Vidyun Sabhaney, including not only visual forms (such as the wall art discussed above) but also performance traditions (such as puppetry). As Sabhaney explains:

"While in a comic image and word are both graphically represented to enact a story, these traditional storytellers perform images through oral narration and/or song. For example -- practioners of Bengali Patachitra (West Bengal) unfurl a scroll composed of sequentially arranged images and bring them to life through song. In the case of Chitrakathi (Maharshtra) a potha or loose collection of painted images is revealed page-by-page while the narrative is sung...Coming from a predominantly oral society, rarely do performers rely on any written text -- in fact, most improvise the dialogues in the course of the performance. Every time a story is performed in these traditions, the telling is different, the artist being at liberty to develop the narrative as pleases him -- within certain boundaries which are defined by the version of the epics that is traditionally performed."

Sabhaney notes that the translation of these techniques for the printed page in terms of contemporary graphic storytelling projects raises a range of questions: "Is there anything to be learnt from these traditions? What is the role of the image in the telling of the story? How is the role of the image in a performance-based practice relevant to us?... Is the unique graphic novel format allowing for the emergence of new voices that have previously been unheard?"

A key point here is that the visual style is not only traditional, but the stories most often told are grounded in India's mythological traditions, especially stories drawn from the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, and various local legends. These stories have long been expressed across a range of graphic forms. For example, below are two examples of art we encountered during our visit to the 13th century Konark Sun Temple in Odisha: the first shows the stone carvings, often highly erotic, found within the temple itself, the second a more recent painting depicting Jagaannath, who has a round, expressive faith, which in many of the drawings, seems a bit like a black-faced minstrel. He is often described as “Lord of the Universe” and especially characteristic of this area. He is one of many personifications of the god Vishnu.

At the gift shops around the outskirts of the Sun Temple, you can find many crudely painted versions of Jagaannath, as rendered on bottles or coconuts, suggesting that, like a good cartoon character, his face can be reproduced quickly, in a range of different contexts, and still draw a smile.

And here are a few more examples of the decorative dimensions of contemporary and classical Indian culture -- on the one hand, pretty much every truck we saw in the country had hand painted patterns on the sides, and on the other, part of the experience of staying in a high class hotel in India is to see elaborate floating flower arrangements created afresh each morning.

One of the few things I knew about Indian comics prior to this trip was that they relied extensively on India's mythological traditions. Perhaps the best known Indian comics, around the world, are the Amar Chitra Katha books.

Across several decades, this publishing house sought to introduce Indian youth to their history and traditions via comics, not unlike the Classic Illustrated books published in the United States. Altogether, they did stand-alone comics which told more than 384 stories and reached 86 million readers. These comics have been translated into an incredible 38 languages and thus have been widely read world-wide. Abhimanyu Das, one of my students at the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program, produced a thesis looking extensively at the ACK comics in relation to the role of graphic storytelling in developing a public culture in India.

The ACK tradition still exerts a strong influence on contemporary graphic novels in India -- while they are often framed in terms of a critique of the traditional values embraced by the earlier publisher, it is striking how many of the graphic novels I encountered there still take as their core subject matter either aspects of the Hindu mythology or key historical figures. In America, the underground comics artist had to work through the legacy of funny animals and superheroes before they could tell a broader range of stories, often inverting or subverting the previous values expressed through such stories. Something similar is happening in India today, and we can see Bhumayana as a prime example of this process at work.

Next Time: The Political Dimensions of India Comics