Marching to a Different "GumBeat"

/ This summer, 45 Singaporean students, drawn from many of the island nation's universities, colleges, polytechs, and art schools, came to MIT to work with students from Comparative Media Studies and Computer Science through the MIT-Singapore GAMBIT games lab. The lab, funded by the National Research Foundation and the Media Development Authority, functions both as a training program fostering new talent and as a incubator for new approaches to game design, both of which will help recharge games as a creative industry in Singapore and, we hope, inform discussions of games as a medium around the world. It does so by putting Singapore and MIT students on teams which work together all summer to develop playable games which we hope will stretch our understanding of the medium. Having attended the roll out of this summer's games and having recently seen the Singapore students demoing what they created at a Pan-Asian games industry gathering in their home country, I have to say I am tremendously excited at what the GAMBIT teams have been able to achieve.

You can see the games for yourself – they are available for download online. Some of them are already generating healthy discussions.

This summer, 45 Singaporean students, drawn from many of the island nation's universities, colleges, polytechs, and art schools, came to MIT to work with students from Comparative Media Studies and Computer Science through the MIT-Singapore GAMBIT games lab. The lab, funded by the National Research Foundation and the Media Development Authority, functions both as a training program fostering new talent and as a incubator for new approaches to game design, both of which will help recharge games as a creative industry in Singapore and, we hope, inform discussions of games as a medium around the world. It does so by putting Singapore and MIT students on teams which work together all summer to develop playable games which we hope will stretch our understanding of the medium. Having attended the roll out of this summer's games and having recently seen the Singapore students demoing what they created at a Pan-Asian games industry gathering in their home country, I have to say I am tremendously excited at what the GAMBIT teams have been able to achieve.

You can see the games for yourself – they are available for download online. Some of them are already generating healthy discussions.

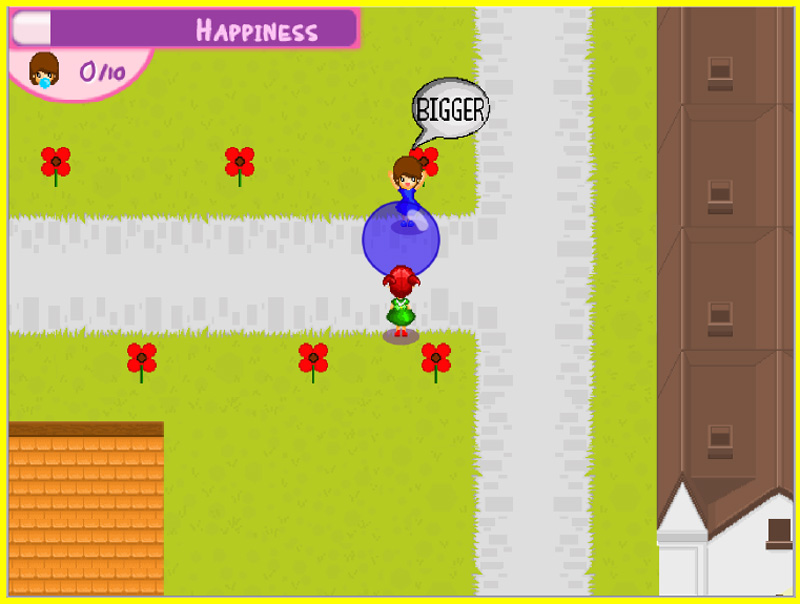

A case in point is GumBeat. Here's how the game was described by the Singapore Straits Times:

USE THE cheery pink power of bubblegum to convince your fellow citizens to join a popular revolt against a repressive government.

While doing so, you stop policemen by popping bubbles in their faces.

This is the premise of GumBeat, a new video game developed as part of an annual joint collaboration between the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Singapore's digital media students.

How does it work?

Well, the heroine chews on candy and blows them into big pink bubbles beside unhappy citizens in the unnamed country in which the candy is banned.

This cheers them up enough to entice them to join the protagonist in a revolution, mustering enough angry citizenry to overthrow the oppressive government.

This is the aim of the game, said National University of Singapore undergraduate Sharon Chu, who presented her team's game to reporters earlier on Tuesday.

Throughout the revolution, you and your followers must evade or stun policemen trying to prevent your march on city hall by popping the bubbles in their faces.

The game was made to show that games with serious-themes like say, 'political oppression', can be fun, said Ms Chu.

Asked if the unnamed country in question was Singapore, she would only say that 'it is up to the player's interpretation'.

Given that one of the first things many Americans learn about Singapore is that it has officially banned the public chewing of gum, the Singapore media can be forgiven for jumping to the conclusion that the game was made about local politics. *shrug* I couldn't say.

I know that the idea for the game originated in part in a blog post by Matthew Weise, a CMS Masters alum who is now the Lead Game Designer at GAMBIT. In the original post from the GAMBIT blog which I crossposted here, Weise talked about his experience of watching the film Persepolis and his desire to see a game which really put us inside the mechanics of what it was like to survive and perhaps resist in a repressive society. Here's part of what he wrote at the time:

The goal of a game like this, from the player's perspective, would involve two distinct

aspects:

Firstly, the player would have to learn the behavioral rules of the repressive society.This would be necessary so that the player could be invisible within the society in order to be able to subvert it. This layer would be somewhat like a stealth or spy game, in which players must learn to dress, act, and talk a certain way in order to avoid suspicion. Only instead of some military espionage scenario, the environment would just be everyday life.

Secondly, the player would have to perform acts that would affect the happiness levels of the society at large. This could manifest concretely as a list of civil liberties which the citizens don't have. Restoring each one of these liberties would be a goal of the game, like a series of non-linear missions. Once all the liberties were restored, the society would be transformed.

I was part of the early conversations with the GAMBIT team where they struggled with what it would mean to represent such political processes in a game and how one could still produce a game which was "fun" but dealt with these themes. I went away on vacation and came back to discover that they had come up with this distinctive approach, reflecting their own experiences growing up.

Joshua Diaz, a CMS Masters Student who was a "product owner" on the team and thus helped to shape the development of the game, has recently posted his reflections on the production process at the GAMBIT blog:

During the prototyping stage, they narrowed in on some basic concepts and hooks that would persist throughout the entire project: gum, police, impressing crowds, popping bubbles, and tagging NPCs with gum. Once they'd established the basic context, Nick Ristuccia designed several different mockups. Perhaps the most impressive was the live-action version of GumBeat that they ran; students sneaking through the lab, lifting sodas and smuggling them back to their lab. The use of a physical, tangible, active test session gave them access to a lot of mechanics that survived the development process and persist in the game you can download today. This was followed by numerous board and paper versions of the game, allowing them to experiment with different mechanics and verbs....

One of the successes of the game was the establishment of several different goals for players. The narrative has a a single driving goal and a short epilogue, but the way multiple gameplay systems combine enables a few open-ended challenges. Feel free to collect not just 10 but 20 or even all 30 citizens; try to max out the city's happiness (no, I don't know exactly what that means, philosophically, but roll with it), or trick the police officers into assaulting each other as supposed chiclet activists. As The Only Haven You Can Trust notes, these kinds of varied goal structures can be a powerful hook in a game's design, and I believe this sort of gameplay is definitely a result of the kind of player-focused testing strategy that PanopXis maintained as a core principle of development.

We are hoping that the game will help spark more reflections about what it means to create a "serious game" and how "serious" serious games need to be. We hope it will get people thinking about game mechanics as embodying social systems through their procedural logic, to channel Ian Bogost for a moment. And we hope that such conversations may lead you to check out the other games to come out of GAMBIT this summer. I'm sure I'm going to be talking about some of the others here before much longer.