Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis: Suzanne Scott & Camilo Diaz Pino (Part I)

/Camilo Díaz Pino

My personal relationship to popular politics far precedes my scholarly engagement with Cultural Studies proper. I was born during the waning years of Pinochet’s regime in Chile, and my parents moved us away from the country shortly before the return of formal democracy. While they didn’t take as many open risks as some of their friends, both of them were active in their opposition to the regime at the time, and like all Chileans who lived through that period, their lives and ongoing behavior have been shaped by the cultural traumas of state terror. Much of the damage done to Chile’s social body during the dictatorship hinged on the regime’s concerted efforts to incapacitate popular collective political action — damage we can likewise now see in the United States, though it occurred very differently here. In Chile during the 1970s and 80s this was done most visibly and notoriously through violent political repression, but also insidiously through neoliberal policies that sought to disintegrate any and all institutional frameworks that fell outside of (or subverted) governmental or business hierarchies. My mother, Walescka Pino-Ojeda, has for her part dedicated most of her academic career to analyzing this very phenomena and its aftermath.

In the years since the re-establishment of formal democracy, Chile has often been hailed as a success story both for its implementation of neoliberal state structures, and later its creation of governmental policies seeking truth and reconciliation for past atrocities by the junta. This was an uneasy compromise; a kind of Third Way liberalism for the traumatized. The inherent structural contradiction of these two processes (attempting to create social unity within mechanisms that were created in part to paralyze the populace away from social-political action) came to a head with an outbreak anti-neoliberal popular protests in the 2010s. These waves of (still ongoing) activism were, at the time, novel in their ability to both mobilize a critical mass of Chileans from across the demographic spectrum, as well as successfully occupy and negotiate public spaces and forums. Perhaps predictably, these have largely been led by the first generations of Chileans to be raised outside the bounds of active state terrorism.

I see my own work as an academic now as an extension of the cultural activism and critical subaltern memory-keeping that these waves of direct political action both correspond with and contribute to. This work shares a direct continuity with the cultural production, scholarship, and political action undertaken by several interconnected underground networks during the dictatorship. These networks were themselves also largely transnational, fueled both ideologically by de-colonial Tricontinentalism, and tactically by the broader lived realities of the CIA-backed dictatorships and US-sponsored state terror that was ongoing in Latin America during the 1970s and 80s.

Now working in the United States, my engagement with participatory politics focuses on the ways in which popular subjects and cultural landscapes have been shaped by such transnational flows of exchange. I’m particularly interested in the ways in which these are affected by often overlooked avenues of cultural intermingling — those taking place in popular media circulation, but also those skirting the edges of power, travelling trans-peripherally, rather than from (or through) centers of global political power. As such, my work has concentrated on both the popular impact of Asian (Japanese, Korean, Turkish and now Indian) culture in the Latin American popular consciousness, as well as the ways in which these are forming an emergent imaginary of activism and the consolidation of new social-political agendas.

Like many scholars, I’ve taken a growing interest in the seemingly sudden awakening of an organized left in the United States during the Obama administration (and heightening in visibility in the aftermath of Trump’s election). Part of my attention here is on how these movements reflect (and in some cases have been informed by) similar modes of activism that started roughly a decade prior in places like Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador and Chile. I’m particularly interested in the recent emergence of social media based networks of global exchange established between activists working within the U.S. and those who have for years been active in confronting state-sanctioned violence elsewhere.

An anecdote from the height of the Black Lives Matter protests comes to mind, in which I saw a flurry of tactical advice given by Palestinian activists to BLM protesters. This focussed mainly on avoiding containment tactics and protecting participants from riot weaponry. For me, moments such as these evidence a true breaching of our old state-centered models of center-periphery dynamics and politics. In this exchange, these Palestinian activists were conceptualizing the BLM movement quite pointedly as integrating a wider network of post-colonial struggle. This globalist vision indeed recalls Che Guevara’s Tricontinental theory, but also extends it towards a conception of peripheral identity that doesn’t see the U.S. as a monolith of external oppression, but as a state that, like the so-called third world, depends structurally on a “internal” exclusions and exploitations as well.

Suzanne Scott

For better or for worse, I ended up doing the bulk of the work on my book, Fake Geek Girls: Fandom, Gender, and the Convergence Culture Industry, during the first years of Donald Trump’s presidency. You can see the traces of this throughout the book, most actively in the introduction, “Make Fandom Great Again,” which modifies Trump’s campaign slogan to make explicit connections between sexist, racist, and xenophobic strains of nostalgia in fan culture over the past decade and the rise of the alt-right and our current political moment. Much of my interest, then, is in the gender politics of participation, and how these are either tacitly endorsed by industry (in the form of various legal and ideological “terms and conditions” that attempt to standardize fan culture in order to better capitalize on it) or by intra-fannish boundary policing practices that restrict who can claim an authentic fan identity and privilege a conception of fandom as a preserve for white, cishet men.

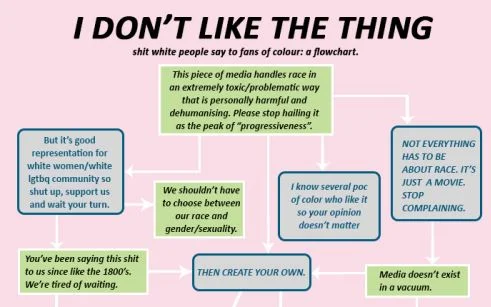

With that said, I vividly remember the reactions that rolled in when it was revealed that over 50% of white women voted for Trump in 2016, which ranged from performative shock to knowing dismay. I was in the latter camp. Even growing up in one of the most liberal areas of California, being upper middle class I had plenty of friends whose parents (quietly) voted Republican for the benefit of their own wallets and at the expense of a wide array of social justice issues that didn’t directly impact their daily lives. While we recognize that sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, sizeism, and xenophobia exist within fandom and participatory cultures more generally, too often we align this exclusively with the bigoted behavior of small collectives of white, straight men. Not without good reason, in many cases, but one ramification of this is that our conversations about “toxicity” in geek culture tend to be inherently limited to discussions of “toxic masculinity” that rarely take into account the roles that white women play in propping up systems of power that they also might benefit from.

In other words, if we are to talk about the potentialities of “participatory politics,” I think we also need to grapple with those who might be hindering real change (however unintentionally) or the ways in which our valorization of “resistance” narratives also produce blind spots in our consideration of white, female fans. As a woman and as a fan scholar, I understand how easy it is to intellectually and emotionally invest in celebratory accounts of the feminist and potentially activist valences of female fan culture (even when they are coded as or problematically presumed to be white and straight), and I also get on a very visceral level why many would be reticent to have that conversation. I also want to be clear that I’m not saying anything here that scholars like Rukmini Pande, Kristen Warner, Benjamin Woo, Rebecca Wanzo, Zina Hutton, Dominique Deirdre Johnson, or Mel Stanfill (to name just a few) haven’t already said about fan spaces. But, increasingly, I find myself interrogating the spectrum of white female fan culture, which can range from activists and allies to white feminists and TERFs to female fans who are as expressly racist and homophobic and invested in maintaining patriarchal power as their male counterparts. One current project I’m working on in this vein is an analysis of the overwhelmingly white female fans who advocated for the reinstatement geek culture commentator Chris Hardwick in the wake of sexual assault accusations in 2018, through an analysis of fan activist hashtags on social media and petitions like this one.

I close my book with a discussion of “fan fragility,” which obviously plays off of Robin DiAngelo’s discussion of white fragility, or the defensive moves that tend to manifest when white people are confronted about racism and their own institutionalized privilege. Anastasia Salter and Bridget Blodgett discuss a similar phenomenon in their book Toxic Geek Masculinity (which, sadly, due to publishing schedules I didn’t get to engage in depth), but I deploy the term pointedly to be able to address both instances of racism and misogyny within fan culture that we tend to conceptually associate with white men, but also engage the other end of the spectrum in which white women within both fan culture and fan studies might respond defensively. To put this another way, while we can and should look to the long histories of activism within fan culture for inspiration on how to best cultivate a progressive participatory politics, I also think we need to look at the other side of the coin, when activist intent is limited or fails to be meaningfully inclusive. Many folks are currently doing work on the more “reactionary” strains of participation within fan culture, but what I would actively like to discuss as part of this conversation about the potentiality of participatory politics is how best to hold ourselves accountable in the work that we do.

___________

Suzanne Scott is an Assistant Professor in the Radio-Television-Film department at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Fake Geek Girls: Fandom, Gender, and the Convergence Culture Industry (NYU Press, 2019) and the co-editor of the Routledge Companion to Media Fandom (2018).

Camilo Diaz Pino holds a Ph.D. in Communication Arts with a focus on Media and Cultural Studies from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His research concentrates on global media circulation, cultures of media production and re-mediation, and dynamics of intercultural cultural transformation across global peripheries and emergent media production cultures. He is presently an Assistant Professor of Media and Culture at West Chester University of Pennsylvania