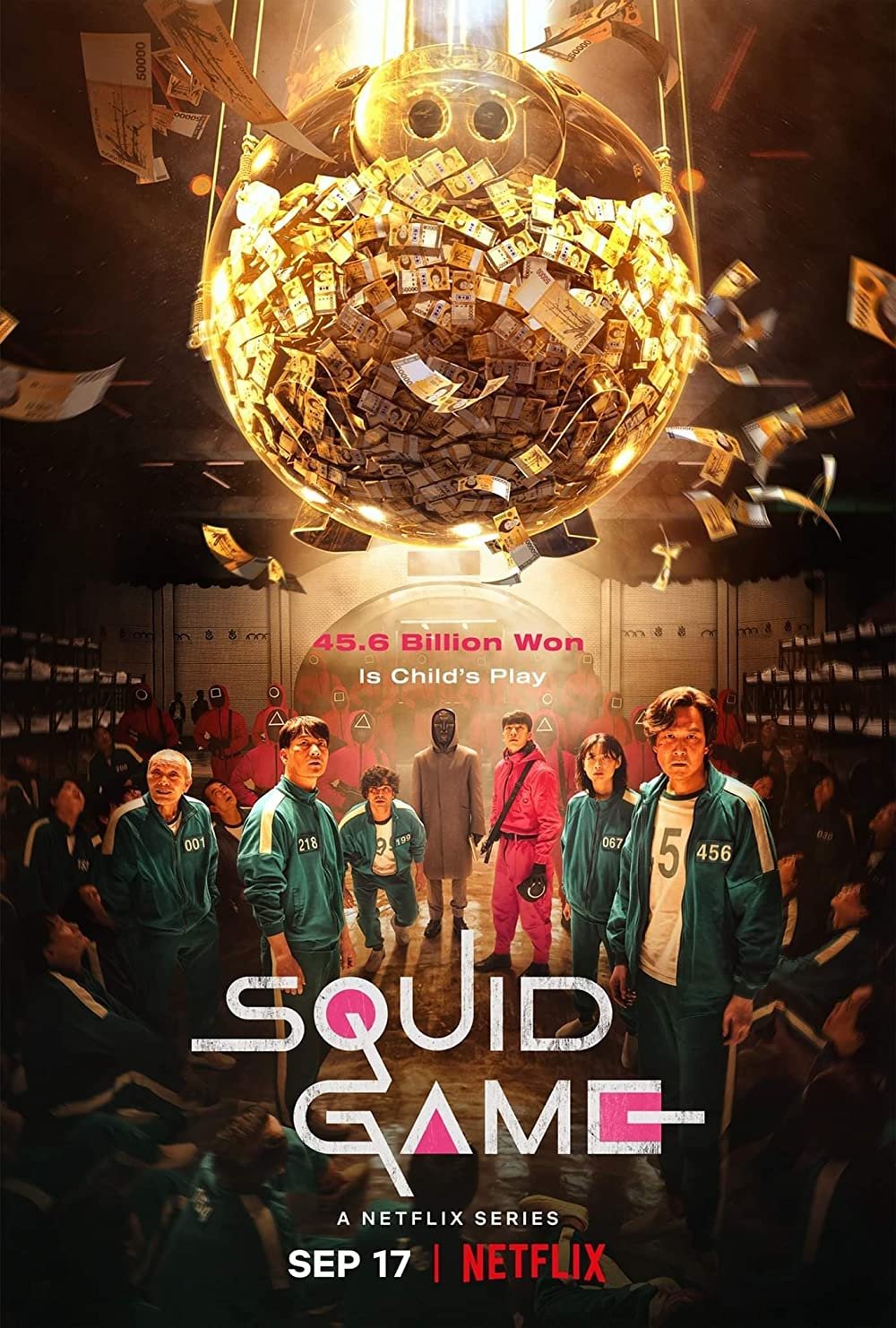

The Joy Kill Club: On Squid Game (2021), a Roundtable-Monologue by a Korean Female Aca-Fan (Part One)

/This week, we take a break from the Global Fandom Jamboree to catch up on Squid Game, which became the top rated streaming program in more than 60 countries around the planet, and has inspired rich discussions where-ever it has been viewed. Do Own Kim, one of my PhD students, shared her mixed feelings about the series and its success with me, and I asked if I might, in turn, share these Korean reflections on the series with my readers.

The Joy Kill Club: On Squid Game (2021), a Roundtable-Monologue by a Korean Female Aca-fan

By Do Own (Donna) Kim

Netflix’s Squid Game (Hwang, 2021) became a global hit. I am a Korean woman, a media fan, and a communication PhD Candidate at the University of Southern California, USA. As an aca-fan, it is both extremely joyous and painful when a media text enthralls my mind. Like a summer crush, I must swoon, ache, and share before the heat passes. So here is my confession, originally confided to Prof. Henry Jenkins via email. Many spoilers.--------------------

I think Squid Game was a rich text and a generous reader in me can write a long eulogy on it as a critical spectacle on the disparities in, and caused by, the paradoxical promise of equity within capitalism. Then, a killjoy reader in me would respond by pointing out that it indeed was a spectacle, and perhaps one at the expense of those who the show claimed to advocate for, and one that nihilistically pointed at our helplessness towards it. At the same time, the generous reader can pounce back at that criticism by arguing that the show reaches its critical potency when we include the fourth screen: by equating the audience as the VIPs in the show. We too were observers of the violence who bet on and rooted for our champion(s), possibly with our own glass of evening drink. This disruptive reflection implies that it is the viewers who ultimately can uproot this game. After all, in a capitalistic society, isn't it all on the demand and supply graph? To this, the killjoy reader would respond with a piece of "real life" that contradicts this critical potential: how the director simply deflected the feminist "controversy" by claiming that he "had no intention of demeaning, hating women" but just wanted to emphasize what humans would do in dire situations and at the apex of indulgence. In the Korean society, feminist readings are still considered as uncomfortable oddities or indeed “killjoys”. Just like the marginalized Squid Game participants, such a reading becomes disqualified by the game maker: the director.

Here is the full conversation. This is a conversation between my two selves: a generous reader and a killjoy reader. This is a methodological exercise, as well as an honest reflection of the busy excitement that overtook my mind.

Generous Reader: G

Killjoy Reader: K

G: It was a fun show. It also seemed to have tried their best to represent as many minorities as they can, such as labor union (the main character's backstory about working at Double Dragon Motors is highly reminiscent of the Ssangyong Motors labor strike), women, youth, the elderly, people with disabilities, international folks, non-East Asian people of color, North Korean refugees, etc. At least in comparison to what’s typical in Korean media. It has its faults but has given some, and mostly positive, narratives to these characters. Unlike much Korean media, Squid Games gives them names and voices. And the series suggest not only how the Korean society's capitalistic system has been affecting these people’s lives but also offering no escape from the reproduction of the same patterns.Squid Game offers only an empty promise of "equality" (not equity) for the disadvantaged.

K: But how did the show use these marginalized groups towards its narrative? As a Korean critic suggested (Text in Korean. Google Translate seems ok), if we were to pick one group that the show championed, ultimately this show was an ode to Korean middle-aged Men, a redemption arc for the "innocent/naive" [soonjin] patriarchs. What the show fails to delve into is how Gi-hun, the soonjin father, was born into the role of the protagonist, both narratively and socially. It overlooks who have been sacrificed either to make Gi-hun’s journey more arduous as a protagonist’s quest should be or to further legitimize the protagonist's status as the hero. Let's first talk about gender. The presence of Sae-byeok (the North Korean refugee character) and ironically Mi-nyeo (“the whore") would improve the results, but a simple Bechdel test would make the narrative build even more evident. What led to Gi-hun’s downfall, i.e., conglomerate greed and labor in Korea, is an issue that direly needs more attention, but what was coupled with it and ultimately excused? The non-demanding, selfless love and sacrifice of old mothers. The seemingly "heartless" ex-wife and her "better" new husband, the "rich dad" (let's not delve into how he showed up to his ex's house and shouted at her, as well as how he reacted to the new “richer” husband’s plea to leave his family at peace). The daughter that repeatedly gets overlooked and deprioritized from the very beginning of the story to the very end, which includes the daughter's own beginning—her birth. Or simply erased, until when the protagonist's well-meaning nature or inner conflicts need to be reminded. The death of the story's strongest female character, who awakened the hero just in time for his noble, bloody “fight" with the hero’s negative parallel, Sang-woo (the smartie). Of course she does so only after she had delegated her purpose to the hero. At the end of Season 1, Gi-hun chooses to re-join the Squid Game to "break the chain" instead of going to LA to visit his daughter: the hero's ultimate sacrifice. But at the expense of whom? Traditionally in Korea, it was socially acceptable to say that "men should do big things (dream big; do important, non-domestic things).” Gi-hun has always chased big things. He is still the hero.

G: Wouldn't that make the protagonist an imperfect hero instead? One that further emphasizes the cruelty of Squid Games that we are all playing. All are suffering, and the fact that you are finding the protagonist's action paradoxical perhaps itself evinces the critical resources the narrative provides for the audience. Behind what may seem like a glamorization, there are such criticisms towards those who may blindly relate to the protagonist, though not without empathy. The only way to stop playing Squid Game is to not participate or to vote together against it. But we are already in it, so perhaps the most agentic choice that we can make is to play it with the goal of dismantling it. This requires sacrifice in which we should think about the collective over the individual. Although it is unfortunate that the domestic life and women’s struggles was chosen as what could be relegated to the “personal,” Gi-hun’s arc can still empower those who may have felt powerless against capitalist oppressors. The oppressors which constantly discourage and threaten people from coming together, indeed at times holding people's private life, domestic peace, and individual purposes as captives.

An example that shows how Gi-hun "earned" his redemption is the contrast between the way the show depicted Gi-hun and Deok-su's (the thug) gambling. Deok-su’s gambling habits were exploitative and purely out of greed. And this exploitative greed continued in how he played Squid Game (e.g., during the marble game). On the other hand, Gi-hun had no other means but to turn towards gambling after his union lost their fight against the big company—whether it be race horses, the claw machine, the flip challenge, or how he gambled by siding with the marginalized during Squid Game out of good faith, etc. He meant well; yes, there was human weakness but also the genuine desire to treat his mother and daughter better. What options do the disadvantaged have? He never returned to the race tracks after winning the game. Gi-hun in episode 3 says "I'm sorry but I'm not in the position to help anyone" when the cop (Jun-ho) asks for Gi-hun’s help in finding his brother. Later he turns into a person who tries to help everyone despite his position. We should also not forget this cop's heroism, although in his case it was partially personally motivated. While to a degree he had to overlook injustices during his undercover at Squid Game, he risked everything to both learn more about his brother's disappearance and to help the world know about Squid Game.

K: But did those who had to suffer from Gi-hun's gambling also resort to gambling? His mother, for instance, labored on without a shop while being sick. The moms fed their respective sons, Gi-hun and Sang-woo, with honest work.

While staying on the topic of gender, how was Squid Game? It, perhaps as a self-mockery, continued to police people based on the facade of equality. The game switched off the lights during the glass bridge stage when the glassmaker, after decades of blue-collar work, was able to use his expertise and experience towards winning. The types of games themselves were gender-biased. In episode 3, characters talk about the nostalgia in the game structure, trying to guess what may come next. This nostalgia is one that is based on the middle-aged Korean Men's (or director’s) childhood where their "moms used to cook dinner,” and the "wives [were] very busy preparing boxed lunches every morning.” Gendered domestic labor is romanticized. In fact, Gi-hun earlier also casually says to Il-nam (the old man or Gganbu) that Il-nam should rather be at home being served warm dinner by his son's wife. Il-nam quips back by asking Gi-hun whether he has done that for his parents, which is a conversation that further adds to Gi-hun's narrative incompetence as a Son and a Father. It is a gibe at Gi-hun’s position which comes at the expense of the hypothetical wife. Gi-hun also explicitly says that Squid Game is reminiscent of the games that they used to play during childhood. Nostalgia is first mentioned without distinguishing genders, then is followed by a clarification that boys used to play the flip game (Squid Game invitation game) and various tag games (I'd like to note that some of these “male" games were indeed played by girls as well). Then he says that girls tended to play some other games, such as rubber rope game [gomujool]. The show later mentions that female characters may be useful for team strategies because of their gendered knowledge about girls’ games, but none of the games that are designated as for girls appear on Squid Game. Ultimately, the games, including the final game—i.e., squid game, tended to be boys’ games that privileged gendered childhood knowledge and physical strength. That is, for instance even if Sae-byeok survived until the end, would she have been able to win? Would she have known the game as a woman, as a North Korean refugee, a younger person? The squid game was depicted as "the most violent game among children's games.” Even if she knew the game, would she have been able to win against the physical strength that the two men so viscerally flaunt during the last game? She was depicted as resourceful and strong, but with the aid of her pocket knife, a tool.

Speaking of tools, Mi-nyeo ("the whore") brought her leisurely pleasures of small transactional value (cigarettes) and unexpected use (lighter) by hiding them in her "womanly pocket,” the only character shown to use their “bodily pocket(s).” This scene highlighted her unsavory tendencies and short-sighted greed, rather than simply her resourcefulness and cunning. She uses her sexualized body as a tool from this moment on. She shouts "sexual harassment" to one of the masked game staffs to help Sae-byeok’s ceiling adventure, of course not necessarily for pure goodness like Gi-hun. Sex crime is a serious issue in Korea ([a] [b] [c] c.f., Global Gender Gap Report) and unfortunately, many men still claim that they are at the risk of false accusation and exploitative "flower snakes" (gold diggers) who intentionally use their sex to exploit men. Mi-nyeo constantly emphasizes that she is not old, casually repeating the word Oppa (the word for older brother for woman. Also colloquially used by women to call men who are older than themselves, although at times with misogynistic connotations that are linked with lower positioning of women, subservience, and appeal to cuteness), always trying to side with the strong (eligible men), only screaming for female solidarity when she got cornered.

She hastily exchanges sex for her protection, which the director described as a scene to show what people could do in extreme circumstances. But was it the only option? Was she, a woman, the only person who was in an extreme situation? It's difficult to retort if the show claims that this was to show her unique short-sightedness, but as a woman, I couldn’t stop thinking that her action seemed like an extremely endangering option or not even a realistic option, especially in a place where even the dead bodies of a woman can get group-raped (suggested via masked organ harvesters' conversations). The print on the lighter she uses suggests that she might have been a sex worker (“Pretty women rest stop [mi-nyeo hyugesil]”); this additionally adds to the narrative trope. Mi-nyeo, as someone who sells her body, is a degenerate whore, a scoundrel, a villain. Unlike Gi-hun’s arc, her redemption is based on personal revenge, not goodness in favor of the collective. Is this the only possible route for "the whores"?

What is more concerning is its resemblance to a Korean historical figure Non-gae, who during the 1500s war killed a Japanese general by seducing him and then commited suicide by jumping from a cliff with her hands clenched to his body. I think it is an unfair stretch to say that this was what the director drew on, and I don’t believe so. It is not the intention nor the potentially defamatory parallel that disturb me. It's with how incapacitating it feels as a (Korean) woman to see yet another narrative where sex and self-sacrifice are depicted as important tools that a woman can, and potentially only a woman can contribute to one's personal gain and/or the greater good.

Was Mi-nyeo a dynamic character or a generic one that was used as an object to advance the narrative, (as the director claimed) to emphasize the direness of the situation or human nature? I personally believe there were too many unnecessary inserts that used gendered violence and tropes to emphasize the theme of the show. During the marble game, did we need to hear the “witty” wordplay between Deok-su and his follower thug about who knows better about how to shove something into a hole? We already knew their characters at this point. Did we need to know that the masked organ harvesters raped a "dead" female participant(s)? Violence was already well-established. If this was a way to propel the cop arc, was it the only way to tell us that the "zombie" was not the cop’s brother? Did we need constant inserts of the women-animal-furniture during the VIP scene? A generous way to put this would be to say that it was a visually-interested homage to Clockwork Orange (1971), one which oxymoronically co-existed with Squid Game’s noble protagonist.

What role did Ji-yeong (the domestic sexual abuse survivor or "the other young woman") serve? The potential in the camaraderie between women or more broadly marginalized people, the potential of non-violent options, the potential of learning about people’s lives, where did these “feminine” alternatives ultimately lead to? Both of the women's deaths. These alternatives weren't enough, and someone had to die. Moreover, her sudden introduction to the narrative and the lack of a fully fleshed-out backstory that focuses only on her added to the impression that she was a supplemental character for Sae-byeok’s story or a character to fulfill a representative space for sexual and domestic victimhood (perhaps as a "saint/Madonna/child" because she, unlike Mi-nyeo, turned out to be a pure victim despite her initial negative mannerisms). And perhaps also, or ultimately, the two faces of religions—more specifically Christianity. I'm not religious myself and there definitely are religion-related societal problems in Korea, but I didn't personally love this one-dimensional portrayal of faith; insufficiently contextualized atheistic ridicule can also be discriminative. Another reason I question Ji-young’s narrative purpose regarding religions is because there is a narrative closure to the criticism on Christianity when Gi-hun wakes up to a caricature of a person shouting "Believe in Jesus! Hell to Non-Believers!" after winning the game.

While watching Squid Game, I thought of some of the survival or society-building genre media that I have read in the past. Many of them, such as Suicide Island, contain sharp social commentaries but often not without relying on some of these “convenient” narrative conventions, particularly regarding women (c.f., in episode 2, people who start pleading for the game to be stopped are mostly women, with one woman saying “I have a child”). I long for the day that I can be immersed in a survival genre pop fiction world without being attacked by violent as-ifs that hides behind the phrase “human nature.”

Do Own (Donna) Kim is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and a Korea Foundation for Advanced Studies fellowship alum. Donna studies digital cultures and mediated social interactions. Her research interests are at the intersections of cultural studies, technology studies, and computer-mediated communication/human-machine communication. She focuses on practices, boundary-crossings, and Others in human-technology assemblages. She enjoys mixed methodological and interdisciplinary collaborations. Her research has been published in peer-reviewed journals such as New Media & Society, International Journal of Communication, and Mass Communication and Society. She is currently affiliated with the research groups Civic Paths, MASTS (Media as Sociotechnical Systems), and ThatGameGroup.

Prior to joining Annenberg, Donna received her B.A. degrees in Media & Communication and English Language & Literature from Korea University in 2015. She studied at Nagoya University for a year as an exchange student in 2013-14. Donna has lived in five different countries including South Korea, China, Canada, US, and Japan. Her cross-cultural experiences and her advertisement/PR internship at Cheil Worldwide inspired her to pursue her interest in digital communication.

Website: https://www.doowndonnakim.com/

Twitter: @DoownDonnaKim