While new platforms make possible new communication strategies, different candidates, then as now, make different choices about how to deploy those media towards their own goals. Thus, we have seen Obama and Trump deploy social media in different ways. What differences did you find in the way that the candidates deployed, say, the Stereopticon to reach their desired publics? What different notions of civic participation animated those strategies?

The Republicans wholeheartedly embraced the stereopticon. Judge John L. Wheeler’s pioneering illustrated lecture The Tariff Illustrated (1888), which advocated for a protective tariff—the Republicans’ central campaign issue, is really the first political or campaign documentary…a direct progenitor of Robert Greenwald’s Uncovered: The War on Iraq (2003) and Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004). Republicans largely credited Wheeler’s lecture for Benjamin Harrison’s defeat of President Grover Cleveland. Targeting the swing state of New York, it was reportedly seen by 174,000 people while Harrison carried the state by 15,000 votes. Four years later Republicans utilized an updated version delivered by at least five different lecturers as a central campaign weapon. While doubling the number of audience members, they much less success as Cleveland won the rematch. Republicans used the stereopticon lecture yet again in 1896 in the Chicago area where it had not previously been used (Illinois was then considerd the key swing state). Moreover, stereopticon lectures proved very effective in the lead up to the 1900 election with appropriately new subject matter—programs on the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars––advocating for McKinley’s imperialistic stance.

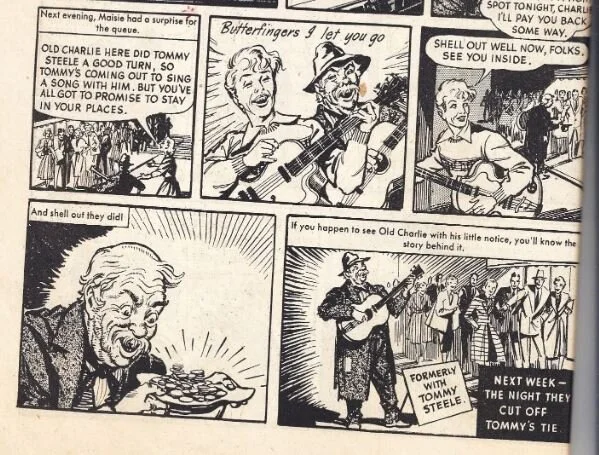

The Democrats were much less interested because they believed they had the major newspapers on their side—which was true until it wasn’t, specifically in 1896 and 1900. But in 1892, many of the Democratic newspapers were prepared to counter Republican efforts and offered mocking critiques of the updated The Tariff Illustrated (1892). Nevertheless, there was no Democratic equivalent. Democrats like Republicans did use the stereopticon as a form of outdoor advertising. In the evening they would project slogans onto outdoor screens, for instance, attacking the Republican’s protective tariff with “Protectionism is the art of taxing the many for the benefit of the few.” Political cartoons were also commonly shown. This had the virtue and limitation of reaching city strollers of all political stripes. However, their value was modest–- part of the campaign milieu that included campaign buttons, banners and posters.

We have watched the role of the Internet deepen with each election cycle as it reaches a broader cross-section of voters, as candidates learn how to use it, and as it gains visibility in relation to more established mass media outlets. Was the same thing happening in the elections of the 1890s in terms of the different roles these media play in subsequent campaign cycles?

While I would agree with the first part of your statement, “We have watched the role of the internet deepen with each election cycle as it reaches a broader cross-section of voters,” I am not sure that I entirely agree that candidates as a group have learned how to use it more effectively over time. Obama’s campaigns knew how to creatively mobilize YouTube and video steaming but it was so new they had to figure it out for themselves. But YouTube did not play a significant role in 2016. Hillary Clinton and her campaign staff never learned how to use the media of any variety with above average effectiveness. Romney was done in by the iPhone which surreptitiously recorded confidential talk to potential rightwing donors. The early 2020 Democratic presidential primary debates repeat many of the same problems evident in their Republican counterparts four years earlier. I am not sure that future candidates will learn from Trump and become skillful masters of Twitter. Alexandra Octavio Cortez is the only Democrat who seems to have comparable talents though to quite different ends. It’s too early to guess if she will run for president and if that will be her preeminent media weapon.

Historical perspective can remind us that the more things change the more they stay the same. Tariffs have become as much of an issue today as they were in the 1880s and 1890s. Who knew? Moreover, there was an obvious if painful analogy between 1884 campaign and the 2016 fracas. A damming letter to Republican candidate James Blaine was made public. At the bottom was a note: “Burn this letter.” His Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland was said to have fathered a child out of wedlock. The Democratic chant was “Burn, Burn, Burn this letter.” The Republican counterpart was “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa?” The candidate who had mail that needed destruction lost to the person with a problematic sexual history. Could history repeat itself in 2016? Indeed, it did: Hillary’s erased emails outdid Trump’s sexual shenanigans. Snail mail and email seem to have made little difference.

As a student of political history, I knew about William McKinley’s back porch campaign, but I did not know the various ways he used new communication technology -- not only cinema but the telephone -- to reach out to voters across the country. Tell us more.

McKinley was the Republican’s premiere orator but he believed he was no match for Democrat William Jennings Bryan. The last thing he wanted to have happen was to go around the country giving speeches with Bryan in his wake. So, he decided to act presidential, stay home and conduct a front porch campaign from his home in Canton, Ohio, even as Bryan toured the country by railroad giving numerous speeches. The difference was striking but also complementary. Bryan used the railroad to get to the people, while the people used the railroad to get to McKinley. They both ended up giving numerous speeches—far, far more than Cleveland or Harrison ever did. Still there were serious drawbacks to McKinley strategy. Presidential candidates were expected to make strategic appearances at key rallies organized in large cities. With Illinois expected to be the crucial swing state in 1896, a huge McKinley rally was organized for Chicago on Chicago Day. Republicans tried to make it an official city holiday. They failed, but employers were encouraged to give their employees the day off if they attended the festivities. McKinley was under immense pressure to make an exception and to attend, but he knew that if he made one exception, he would have to make many more. So, he declined. The techies of 1896 then came up with at least two ingenious solutions. First, with the long-distance phone lines recently installed between New York and Chicago and with McKinley plugged into this new communication system, they installed telephone receivers by the reviewing stand where he should have been located. When loyal Republicans marched by, they were encouraged to shout into the receivers and have their words heard by McKinley in Canton—and his vice-presidential candidate in New York. It was as if McKinley was in Chicago—or more accurately that their voices magically joined McKinley in Canton. The idea was a success and quickly repeated in other major cities such as Pittsburgh and New York.

Motion pictures did the reverse. Abner McKinley brought the Biograph team to Canton where they filmed McKinley in front of his home apparently receiving a telegram. When McKinley at Home was first shown at Oscar Hammerstein’s Olympia Music Hall on October 12th, it was as if McKinley and his home had been magically transported to a theater filled with prominent Republicans and other supporters. Vice presidential candidate Garett Hobart, was expected to be present and shout out a “Hi, Bill” to his running mate. (The elderly Hobart, however, had apparently had enough with new technology when he listened in on the Chicago rally via telephone and did not bother to appear.) In any case, a virtual McKinley was able to stand in for the candidate himself. Moreover, his virtual-self made regular appearances at the Olympia and then Koster & Bial’s Music Hall, where pro-McKinley rallies continues for the next month. New York City actually went for McKinley. New media didn’t just solve a problem, they added something more. The Republicans evidently knew how to innovate. Surely they would find a way to get the United States out of a protracted four-year depression.

Early accounts have tended to treat McKinley at Home as an isolated text. But building on your earlier work which looked at exhibitors as constructing an assemblage of short films you make the case that it should be read in relation to other films shown on the same program. Can you speak a bit more here about the way the McKinley film fit within a larger flow of ideas?

Biograph was a fully integrated company (production-distribution-exhibition) that had full control over the programs it produced, and its creative personnel knew how to make use of that centralized control. We somehow have this view that those involved in cinema were naïve and struggling to find their way—that they just assembled films into some kind of random order because they didn’t know better. In short, editing had yet to be invented and cinema of the 1890s was all about the isolated image as a kind of attraction. In fact, when it came to audio-visual programs, post-production was in the hands of the exhibitor and there was plenty of experience in this area. The Biograph company thus presented a carefully calculated and powerful pro-McKinley motion picture program which made a series of calculated and impressive analogies. McKinley’s image was wrapped in a series of quintessential images of America. These included the legendary actor Joseph Jefferson in a scene from Rip Van Winkle and two scenes of Niagara Falls. There was also a good all-American racial “joke” as an African American woman washes her baby, who despite her best efforts does not become any whiter. All this led up to a McKinley parade in Canton and culminated with McKinley at Home. During a press screening, McKinley at Home was shown last but it was upstaged by The Empire State Express. So, in a strategic move Empire State Express was shown last. It showed America’s famed express train—a technological marvel in itself, depicted dynamically as it raced towards and past the camera and so viewers. But the train, like the Empire State (New York) was also racing ahead for McKinley. Thus, a series of associations or substitutions—American grandeur, American railway technology, Biograph’s superior motion picture technology, and McKinley as a future mythic president. I see this as a prescient form of montage of attractions not simply at cinema of attractions. The onrushing express is like the final shot of Potemkin—the prow of an onrushing battleship.

What did or did not work about William Jennings Bryant’s attempts to expand the reach of his famous oratorical skills using the phonograph?

If motion pictures were seen as the new media dominated by Republicans, the phonograph was viewed as the new media technology ideally suited for Bryan’s talents. In fact, there were numerous technological problems and limitations to phonographic reproduction and production--as well as the brief playtime of a recording—that belied such an assumption. Because Bryan had achieved a special status as an orator and won the Democratic nomination with his “Cross of Gold” speech, people certainly wanted to hear him and were ready to go to phonograph parlors to do so. Although many did hear a small selection of Bryan’s speeches in phonograph parlors during the 1896 campaign, the orator was not Bryan. Correspondingly, they could hear a few excerpts of McKinley’s speeches, but they were not spoken by McKinley. Speakers specifically trained and paid by the phonograph companies provided the voices. Visitors to phonograph parlors often made quick comparisons, sampling recordings for both candidates. Remember, however, that the phonograph companies were generally pro-McKinley. Some reports suggest that Bryan’s speeches may have been subtly burlesqued in their re-presentation. It seems completely credible, though this might have been in the partisan minds of pro-McKinley journalists.

Given this assumed affinity between Bryan and the phonograph, it is not entirely surprising that in 1900 when Bryan had more time to prepare a campaign, the Democratic National Committee arranged to have the candidate and a number of high profile Democrats record master cylinders from which 250 duplicates were to be made. It was widely “expected that the Bryan Speech as ground out by the phonograph will play an important part in the campaign.” In fact, the master cylinders were apparently flawed and the duplicates unusable. A series of lawsuits followed—which the Bryan campaign lost. High hopes came to naught.

How important do you think these early experiments with mediated communication were to the candidates, their campaigns, and their outcomes? Were the uses of cinema, recorded sound, and these other technologies an interesting side show or did they help to shape the outcomes of these elections?

That is a good question and of course there are no easy answers. Mediated communication modes—particularly if we include the newspapers—were crucial to the outcome of these elections. Cleveland’s narrow victory in 1884—thanks to New York’s many Democratic newspapers––proved that. He lost some of that support in 1888 and lost New York State. Certainly McKinley lopsided victory in 1896 was partially due to the fact that all the traditionally Democratic newspapers refused to support Bryan and in effect became pro-McKinley. The stereopticon was certainly a factor in 1888 with The Tariff Illustrated and quite possibly in 1900 with the many celebratory accounts of military victory securing an overseas empire. When going into a campaign, political operatives never know the precise layout of the upcoming battlefield and are looking for every possible advantage. Media was always an important part of the equation. On the other hand, Bill Clinton’s tagline that “It’s the economy, stupid” bears weight. Cleveland may have won the 1892 election because the country was beginning to enter a Depression. It was unlikely that any Democrat could have won the 1896 election given the previous four years of economic devastation. And the rebounding economy of 1900 certainly was crucial to McKinley’s fortunes.

Media, and in the long 1890s particularly new media, shaped the gestalt or, to use Raymond Williams; term, “structures of feeling” of the campaigns. The Republican party’s use of motion pictures and the telephone–-along with the bicycle––gave them a pro-active aura of being up-to-date and if I can use these words––cool and hip. Bryan’s problems with the phonograph did the opposite, calling into question his competence and reinforcing his aura as something of a rube or country hick. This goes beyond immediate cause and effect and takes into account deeper and more subtle influences.

One person who should not be lost in all of this is Theodore Roosevelt. I don’t think anyone had carefully researched and assessed the ways media played a crucial role in his rise to power, but Politicking and Emergent Media covers that ground in ways that readers should find interesting.

Your book doesn’t just deal with the campaigns, but also how the public learned the outcome of the elections. How Americans would have engaged with unfolding election results during the 1890s?

Today we often gather around our TV sets—of computer screens--to watch election returns with friends and family. In the second half of the 19th and first decades of the 20th century, crowds gather at newspaper headquarters to follow the returns since the papers were plugged into the telegraph system that reported the votes in almost real time. In big cities, this reporting of results became competitive. Who could get them first and who could display them in the most entertaining way. At first these returns were posted on bulletin boards. Increasingly they were projected on a screen using the stereopticon. While waiting for a new set of figures to arrive, cartoons, slogans or other miscellaneous materials were projected. Bands might provide music. In 1896 motion pictures were often screened between updates. It was undoubted the first time that many people got to see films for free.

Across the book, you are also conducting a conversation about the disciplinary shift from Cinema Studies (where you situated your earlier work) and Media Studies, Dare I say Comparative Media Studies (where you situate this current project.) Yet, clearly, earlier writers of film history were interested in film’s relationship with painting, photography and various forms of popular theater. In what ways does the new focus on thinking across media break from that earlier tradition? What do you think your project gained from embracing those conceptual shifts?

Thank you for that question. I think we have to remember that Film Studies emerged in the context of a great truism or cliché: “cinema is the art form of the 20th century.” If that was the case, much needed to be done. Filmmakers—major and minor—needed to be studied and assessed. Film works needed to be restored and presented to the public. We needed to understand the history of this art form on a level of detail and sophistication which had not really begun to happen. In this context, I realized that beginnings are important and since little was really known in terms of the formative years of motion pictures, that this was in particular need of being studied. Also I quickly discovered that the questions and answers that came out of such investigations were not necessarily the ones that we would have expected. They made me really think about the very different ways cinema had been cinema over the course of its history. At the same time, this pre-Griffith period was a period before film was considered an art—either at the time or by our contemporaries. So in that respect the study of early cinema was already moving in a media studies direction.

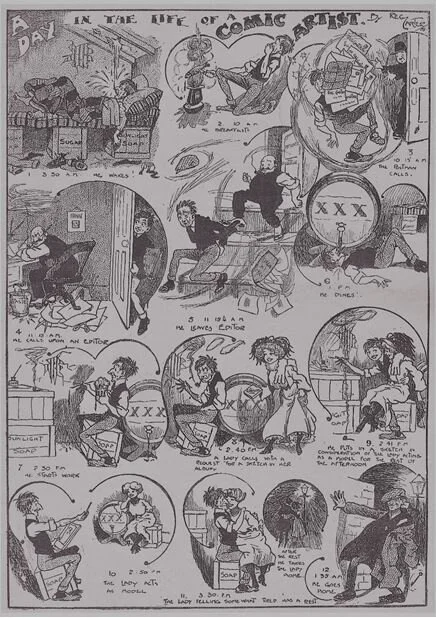

The first fifteen years of my sustained, in-depth investigation into American early cinema (1976 to 1991) were focused on mapping out its history on multiple levels. In this, I obviously was not alone but part of a generation of scholars often associated with the 1978 Brighton Conference. We sought to understand the changing nature of film style as well as the dialectics between modes of production and representation. The American motion picture industry was shaped in many ways by a series of legal battles around patents and copyright. I was particularly interested in figuring out the rapid shifts in cinema practices. We certainly attended to the ways cinema interacted with and appropriated elements from various popular cultural forms in terms of subject matter but also in areas such as exhibition (vaudeville, illustrated lectures and more). We were interested in intertextuality and then increasingly in intermediality. Cinema, however, was always the starting point. Obviously, I wrote about Biograph, McKinley and the way cinema had played an active role in American politics only a few months after commercially successful projected motion pictures appeared in the US. However, because it was always in terms of a history of cinema, such investigations often stopped short.

When people talk about the death of cinema, it is not that cinema died but it ceased to be this dominant art form. With the fading of art cinema, some might argue that it even became a minor art form produced for a modest group of educated cognoscenti; but even if one wants to include major Hollywood blockbusters, its hegemony was broken. Television, video games, the Internet and social media: media studies was really a necessary engagement with a new and very different cultural realm. Although I came to Politicking and Emergent Media through my interest in early cinema, I wanted to decenter cinema and re-situate it in a much broader media landscape. At the same time, a much broader media landscape created problems of focus and shape. Concentrating on U.S. presidential political campaigns proved a clever and effective solution. It enabled me to ask a whole series of new and interesting questions. One of the fundamental questions I had to pursue: what was the relevant media formation for this undertaking. I realized that newspapers were a central component, which quickly put me somewhat at odds with the Amsterdam model of Thomas Elsaesser. It was also essential to include public oratory and pageantry, which did not depend on technologies of reproducibility which extends the range of media that Lisa Gitelman and others had been investigating. The result was a more open-ended investigation with many surprises.

One modest example: I had been interested in the stereopticon but again as part of a history of screen practice as a way to understand cinema’s rapid emergence as a sophisticated cultural force after 1896. So, it required a conceptual adjustment to realize that the stereopticon was arguably a more pervasive and politically influential media form than cinema in 1899-1900, at least when it came to presenting narratives of US imperial conquest. Comparing the role of the phonograph to motion pictures was straight forward but the role of the telephone—and in a different way the bicycle—was completely unexpected. For me it produced a richer and more interesting story—a story that resonates with the contemporary moment but always in unexpected ways. There is no question that Republicans were the party of big business and US imperial expansion but they were also generally more progressive on environmental issues and women’s suffrage. What surprised and intrigued me the most in the course of this undertaking was that Republicans, particularly in the decisive 1896 election, presented themselves implicitly and explicitly as the party of technological innovation and hope, conveying an optimism about the future that would reaffirm Republican dominance in the political realm until the Great Depression.

_____

Charles Musser is a Professor of Film and Media Studies, American Studies and Theater Studies at Yale University where he teaches courses on the history of film and media as well as documentary (both production and critical studies). He recently completed a new feature-length documentary Our Family Album (2018), an essay film on Love, War and the Power of Photography. Its literary counterpart, Our Family Album: Essay-Script-Annotations-images is being published by John Libbey and will be distributed by Indiana University Press in late 2019.