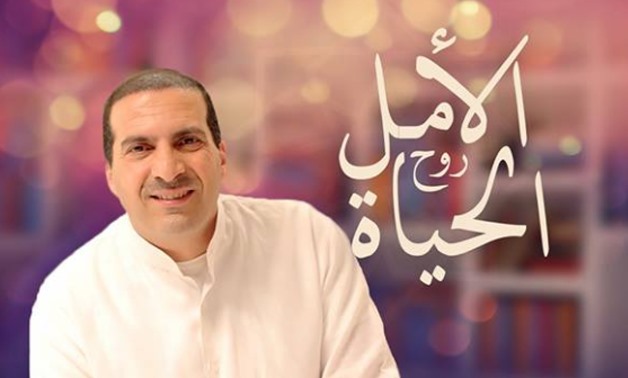

Outside Al Hossary Mosque in Greater Cairo, crowded young, mostly affluent, Egyptians. Their bodies blocked the entrance to the mosque, while their double-parked cars congested its street (a common sight in overcrowded Cairo). It was short after sunset, the time for the then-popular Muslim televangelist, Amr Khaled, weekly lesson. His lesson was about sincerity, which he intercepted with jokes, storytelling and a teary supplication towards the end. It was the start of the millennium, when Amr Khaled seemed to be attracting a strong following of young Egyptians desperate for enchantment in what seemed like a country ruled with an iron fist, when Mubarak was still in power (apparently, it is now ruled with a “steel-fist”). Khaled’s lively lessons and animated character stood in contrast with the traditional cloak-wearing, state-approved Azhar clerks on one hand, and the Jilbab-wearing, arguably state-approved, fundamentalist Salafis on the other. With his shaven face, tieless suite, and wide smile, Khaled looked more like themselves. He enlivened the same stories they monotonically heard as children with detail and personified the Prophet and his companions—from which Muslims draw their life-style—through affective rhetoric. He was soon named by the Times asone of the most 100 influential people in 2007. This arguably put him in a perilous situation with the Egyptian government that was historically weary of religious figures turning popular. Amr Khaled was therefore judicious in steering away from politics. Nevertheless, in the minds of his adoring fans, this left room for speculation as to a possible double meaning in some of his lessons, and/or choice of stories. Soon, there was a wave of religiosity sweeping Egyptian society especially among upper middle-class Egyptians; gradually, many young men and women started practicing religion publicly. They observed their daily prayers and frequented the mosques, especially Ramdan’s night prayers, while many young females started wearing the headscarf.

I was one of Khaled’s young fans, a late-adapter nevertheless (if we can liken Khaled to a new technology). Skeptical of religious rhetoric at the time, I was afraid that someone would make me feel guilty about my wavy hair, tight top and jeans. As a Muslim woman I am required to dress modestly and cover my hair. It was not until, I indulged myself in Islamic philosophy and the writings of Al Ghazali, that I decided to cover my hair during my last year of university against the objection of my family. I was proud to have worn it without the influence of religious figures, or family. At which point, I started listening to Khaled, and was surprised at how he did not limit a woman’s expression of religiosity to the way she dressed as some fundamentalist Salafis liked to do. In fact, very few of his lessons touched upon the physical appearance of the Muslim, whereas most focused on their piety and interactions with society. His words about sincerity, his animated storytelling and teary supplications are still vivid in my memory. I remember them now with bitterness. I, like many of his fans, was struck by what many would describe as Khaled’s transformation.

Following the January 25thuprisings, Egyptian media was rampant with hostile accusations of treason against young protesters who were scrambling for voices of support. To the youth’ dismay, Amr Khaled, whom they brought to fame, stayed silent on the subject. He was not alone in that; many popular religious figures followed suit, or worse, attacked the protests as un-Islamic or unpatriotic. Khaled did not speak, until it was apparent that Mubarak would resign and eventually concede. His statements remained ostensibly impartial, urging “everyone” to exercise temperament. However, with so many victims to state brutality, staying on the side-lines was no longer acceptable to his young fan base, of which many participated in the uprising. His popularity, however, did not sharply sink, until a video surfaced for him following the 2013 military coup where he was addressing Egyptian soldiers and providing them with religiously-framed arguments for blindly following commands. To many in my generation, this was the last straw.

In my research on cultural resistance post-Arab spring, I examinehowthe energies of the Arab Spring have transformed to the participatory, ephemeral and relatively ambiguous spaces of humor, music and creative digital arts. Unable to publicly criticize cultural and political authorities, young Egyptians reveled in their ephemeral digital triumphs over the low hanging fruits of authority, its cultural productions. Amr Khaled, with his watered-down rhetoric, turned from a religious heart-throb to yet another state-media talking head. The prudence that worked for him pre the uprisings, worked against him following the military coup, after countless victims were lost to police brutality. Hence, it came as no surprise that the once admired figure of Khaled on one hand, and the once revered self-proclaimed Salafi Sheikhs on the other, became the object of ridicule in memes and parody videos of online youth. While some may see those parodies as signs of dystopic cynicism, I see them as a sign of maturing sensibilities that reject any attempts at misleading them into previous complacency. Not surprisingly, this was also paralleled by a rejection of favorite childhood entertainment figures, such as Mohammed Sobhy, for their moralistic rhetoric and state support.

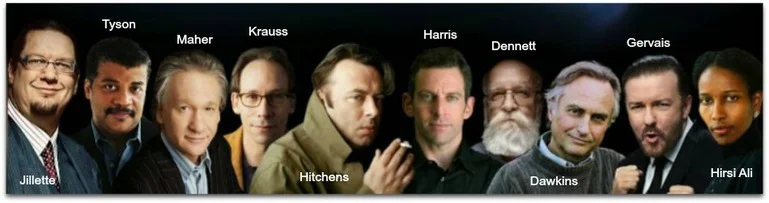

However, this rejection of religious figures should not be mistaken for a rejection of religion altogether; to say so would be disregarding a central aspect of life in the Middle East. It, however, signaled that those young adults were now consuming religion in a much more critical fashion. As someone trained in cultural and post-colonial studies, I continually emphasize that part of the acclaim that the Arab Spring uprisings received from western media analysts and commentators was not only inspired by its promises of political reforms, but also—what some viewed—as a promise of subsequent social reformations to an inherently flawed ‘other’. Such discussions of religious reformations, trying to replicate the Christian reformations, are both patronizing and counterproductive and have little to do with the societies these populations live in, as Shadi Hamid from the Brookings Institute once asserted. An uprising against an old order does not necessarily translate to an uprising against its heritage and tradition; it could rather simply imply a rejection of one appropriation of that tradition but not the other.

While traditional religious spaces may have been viewed as part of the institutions social movements were trying to resist, this resistance may have only been to the state-abiding aspect of these institutions; other aspects such as the religious rituals or promotion of social justice and advocacy may continue to be sources of inspiration to some of the activists. In my research, I have seen youth both emphasizing continuity with tradition side by side to, discontinuity or resistance to some of its state-abiding aspects. So their relationship to tradition, and childhood texts is better described as a negotiation, a site of struggle over the role of religion in their social and political lives; this relationship still exists, however, on their own negotiated terms, ones that do not sacralize individuals all while respecting difference.

Last Ramadan, marked in my opinion a sad, yet telling, ending to the phenomenon of Amr Khaled, when he appeared in an adfor army-produced chicken, emphasizing the need to consume healthy food products, aka army produced ones, to enable proper worshiping in the month of Ramadan. The criticism on social media was predominantly sarcastic. To young adults, the irony was self-evident, yet one mixed with disappointment over what could have been a possible meeting point between tradition and change.I can now see Egyptian and Arab youth weaving this connection in their participatory spaces, breaking the sanctity of individuals on one hand, all while rediscovering what brings them together as Egyptians, Arabs or Muslims.

Nabil Echchaibi

University of Colorado Boulder

I began my work on religion immediately after 9/11, that fateful event that has ushered in a perpetual state of emergency and fear about Islam and Muslims. I was writing my dissertation on second and third-generation French and Germans of North African descent and how they navigated the political philosophies of assimilation and integration in their countries through media production. Up until this moment, these minorities had confronted a relentless form of cultural and institutional racism in which religion didn’t figure so prominently. French North Africans, for example, were referred to as “les Maghrébins” or “les arabes”, terms that were replaced overnight with the ominous label of “les musulmans”. This new ascendancy of militant Islam in the West precipitated a public scrutiny of Islam and exacerbated anxieties about the motives of Muslim minorities. Questions multiplied and quickly turned into paranoid interrogations of the loyalty of Muslims and the compatibility of Islam with modernity.

Suddenly, Muslims were called to provide theological answers to questions about jihad, niqab, hijab, sharia, and suicide bombing amidst a media climate of deep semantic and cultural confusion about the meaning of these words and their relevance in a Western secular democracy.

I became interested in the sources Muslims both in the West and in the Middle East were urgently consulting to confront the suspicious tenor of these allegations. Although these emerging questions about Islam pertained as much to politics and Western foreign policy as they did to religion, Muslims turned to various forms of popular religion to ask their own questions and challenge the narrow premise of fixed binaries and regressive traditions. Oil monarchies of the Gulf flooded satellite television with religious programming, some of which inaugurated innovative forms of preaching and religious entertainment in the form of reality television, game shows, and music videos. The political ramifications of this Islamic revivalism through networks manipulated by Saudi Arabia was hard to miss, but I was also intrigued by the novelty of this style and the large following it commanded around the world.

Popular preachers like Amr Khaled, a former accountant, pioneered a creative breed of religious programming with an effective mix of religion and entrepreneurship. He later adapted Donald Trump’s The Apprenticeto a program about Islamic charity. Moez Masood, a former advertising producer, created a slick twenty-part television series in which he toured the streets of London, Cairo, Jeddah, Al Madinah and Istanbul interviewing Muslims about spirituality, romance, homosexuality, drugs and veiling. And two British Muslims launched a record label company that specialized in devotional music and Islamic entertainment. Critics of this popularized form of preaching called it “air-conditioned Islam’ or “Islam light”, accusing its producers of simply mimicking or importing the religious performance genre that helped popularize American evangelical Christianity through the adoption of modern media and popular culture. I began, instead, to explore the aesthetics and rhetorical import of this televised and digitized Islam in a way that did not dissociate it from the rich history of sermonizing in the Islamic tradition. To me, this phenomenon had more to do with a historical tension within Islam over religious knowledge and its transmission, which made many Western accounts of these preachers too shallow and predictable. Television and the Internet only complicated an oral/aural/visual tension in the devotional experience of Muslims and I wanted to capture that continuity.

The point of my research was not to argue that there was nothing new in these emerging forms of mediated Islam. Rather, I wanted our analysis to also adopt a historical approach which contextualized the complex theological, ethical, and cultural dimensions of mediation and circulation within Islam. This part of my research has largely benefitted from the work of Talal Asad, Saba Mahmood, Mahmood Mamdani, and others who argued, persuasively, for an intimate engagement with the intellectual and political history of Islam in order to recognize the vitality of Muslim efforts to re-articulate their religious traditions and adapt them to their modern condition. This is not simply a return to a bounded notion of tradition, although it is for some, but a negotiation of traditions to make sense of the world.

Drawing on postcolonialism and decolonial critiques, my recent work focuses on emerging material expressions of an Islamic strand of cosmopolitanism that is deeply invested in this effort of sensemaking. I call this ‘Islamopolitanism’, a combination of popular religion and an intellectual engagement with what it means to be modern and Muslim today. Specifically, I ask how our analysis of new Muslim digital spaces and aesthetic formations can reveal emergent cultures of Muslim cosmopolitanism, a cultural sensibility and a way of dwelling in the world intimately born of the complex tensions between religious universalism and particularism, cultural mixity and purity, and authentic piety and neoliberal commodification. I argue that this form of Islamopolitanism is primarily rooted in a cultural aesthetic rather than a political conviction. Its proponents call for a remix of Islamic culture that arguably resists the nativist visions in the dominant narratives of Muslim identities.

It is precisely this epistemic disobedience against the duality problematic of modernity and tradition that is still absent in our accounts of Muslim lived experiences. Moroccan postcolonial thinker and novelist Abdelkebir Khatibi insisted on demystifying both Western and Arabo-Islamic logocentrism in favor of a double critique that springs from tradition but only to create new ideas, new questions, and new ways of knowing. I invoke Khatibi’s postcolonialism in my research because it resists narratives of melancholy, victimhood, shame, malaise, loss, or existential uprootedness. Instead, his invitation was to find a discourse of possibility, an epistemology of suspicion, an idiom of Muslim syncretism, and a path toward intellectual independence.

Other Muslim thinkers call for a similar open engagement with the particularism of Muslim cultures, local intellectual and political histories, and religious doctrines to deliver Muslims from the long grip of the slogans and the blackmail of Western modernity. In his provocative thesis that postcolonialism has ended, Hamid Dabashi argues that we have reached a moment of epistemic exhaustion that marks the “implosion of the ‘West’ as a catalyst of knowledge and power production.” The Arab uprisings of 2011 were, according to Dabashi, only the beginning of this new defiance. Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne, who advocates for decolonizing the history of philosophy, also calls on Muslims to keep Islam an open project, a doctrine in movement ready to drop all forms of identitarian chauvinism and to listen and absorb other voices inside and outside its tradition.

Islamopolitanism is an open-ended project that shares these sensibilities and aspirations. I explore the work of performance artists, activists, devotional musicians, and authors who have developed sites, aesthetics, and cultural tastes to interrogate the mediation of Islam and the making of Muslim subjectivities beyond the limitations of traditional Islam and secular modernity. My aim here is also to expand the object of study in Islam beyond simply the visibly pious adherents of this faith. In fact, what are we studying precisely or who do we focus on when we label our research as work on Islam? My own approach is concerned with unpacking the complexity as well as elusiveness of the Muslim subject. As Achille Mbembe and Sarah Nuttal remind us in their writing about cities of the South and their dwellers as subjects ‘en fuite’ (on the run), I want to theorize Muslims as subjects en fuite- in the sense that they “always outpace the capacity of analysts to name them.”

Kayla Renée Wheeler

Grand Valley State University

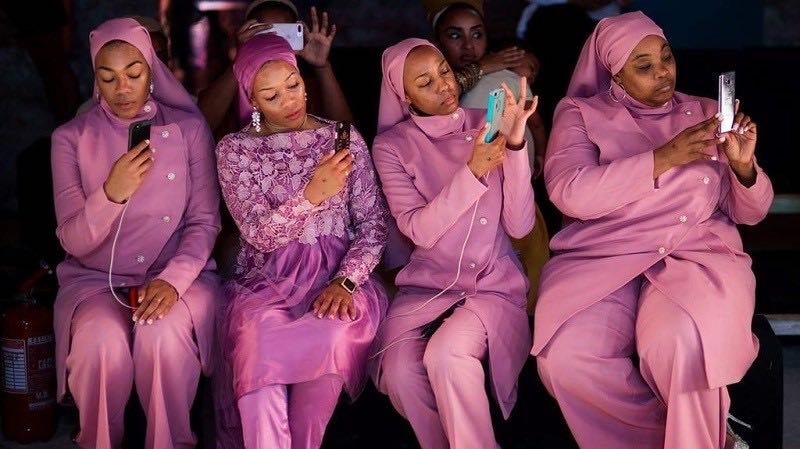

Throughout jumaah at the Annual Muslim Convention, I awkwardly tugged at my khimar. Unlike the times I had spent doing fieldwork in predominantly Arab and South Asian mosques, I wasn’t worried about making sure my neck and flyaway hairs were covered. Instead, I was repositioning my khimar to make my slicked down baby hairs visible and to show off my dangly earrings. I wanted to fit in. I was surrounded by Black women in every possible head covering imaginable: berets, kufis, turbans, hoodjabs, and Shayla khimars. Their wax print and bogolan maxi skirts made them appear to float elegantly down the rows, their layering techniques would have made Bonnie Cashin jealous. They were performing what anthropologist Su’ad Abdul Khabeer calls, Muslim cool, a form of embodied resistance that privileges Blackness. I had finally found home.

My experience at the Annual Muslim Convention was one of the few times where my loosely tied khimar and 3/4-length sleeve shirt had not been met with side eyes from Muslim aunties. None of the aunties at the convention chastised me for not dressing modestly or “Muslim” enough, something that often happens in the small college town mosques that I visit across the U.S. These critical aunties, who are quick to call my outfits inappropriate and even haram, are invested in what I call “hegemonic Islam,” which is Sunni-centric and privileges Arab expressions of Islam as the most authentic based on the belief that geographic or cultural proximity to Prophet Muhammad’s native land dictates one’s religiosity. Hegemonic Islam is naturalized as “true Islam” and marginalizes those who do not fit within its framework. It proves problematic for African-American Muslims who can only trace their natal history to the Americas. Hegemonic Islam is inherently anti-Black because it devalues practices and beliefs created within African-American Islam.

I developed the term, hegemonic Islam, in my dissertation, which explores how Black Muslim women use YouTube fashion and beauty tutorials to create alternative images of the ideal Muslim woman. I traced the development of hegemonic Islam back to postcolonial movements in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) beginning in the 1960s, during which Muslims critiqued Western political and cultural dominance across the world. Many sought to create an alternative shared identity for Muslims that would transcend social class and geography. One way this shared identity was expressed was through dress. Regionally specific clothes and styles, such as the abaya and thobe, were transformed into the only authentic Muslim dress. This new shared identity created a new social hierarchy, where Arab Muslim cultural practices are placed at the top and African-American Muslim practices are at the bottom. Wearing clothes that had once been specific to the MENA region became a sign of one’s commitment to Islam, instead of the materialist West. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer calls this pious respectability, where it is assumed that the more “religious” a Muslim becomes, the more they will shift aesthetically towards MENA. I am interested in exploring how Black Muslim women have used fashion to reimagine pious respectability and resist hegemonic Islam.

In my book, I explore how Black Muslim women in the United States have historically used fashion to construct alternative femininities that disrupt Eurocentric beauty norms and create transnational networks of belonging based on a shared identity as Black Muslims. Through my research, I explore how the Nation of Islam (NOI) and Imam W. Deen Mohammed community’s (IWDMC) emphasis on racial uplift via entrepreneurship and patronizing Black businesses have been essential to building what I call the Afro-Islamic Diaspora fashion industry. These organizations host charity fashion shows, house bazaars at annual conventions, and build women’s only spaces where women and girls can learn how to sew and design, providing women with the opportunity to monetize their talents and promote Black self-determination.

I situate my work within Islamic fashion studies. The field is underdeveloped because scholars have historically understood fashion to be a product of the Christian West, originating in the Renaissance during the rise of early capitalism when people moved to urban areas and sought ways to individuate themselves. These fashion origin stories create a binary between the West as a site of modernity and the East as being stuck in the past, which replicates Orientalist tropes. This leads to scholars viewing Muslim women’s covering practices as static and geographically bound, but that is not reflective of what is happening on the ground. What fabrics, colors, and silhouettes are considered trendy is constantly shifting. Five years ago, Khaleeji hijabs were “in”, now it’s turbans. It has been important for me to avoid looking for motivations as to why Muslim women cover—they are often numerous and fluid. Instead, I am interested in examining what clothes communicate to others, what bodies are produced through dress choices, how definitions of modesty are constructed, and how objects become “Islamic”. This approach prevents me from fetishizing Muslim women and their clothing.

It has been interesting watching the rise of modest fashion within the mainstream Western fashion industry. 2015 seems to have been a major turning point in the industry. Not only did high-end brands like Tommy Hilfiger, Dolce & Gabbana, and Monsoon begin selling Ramadan collections, many of which were only available in the Gulf region, more affordable brands like Nike, Uniqlo, and Macy’s have created permanent lines. In general, the fashion industry has embraced longer hemlines and higher necklines. On a personal note, it’s been so exciting to ditch my collection of cardigans and leggings that I used to use to make outfit more modest because so many brands now cater to my tastes. While the move from body con dresses to maxi shift dresses could be a result of the cyclical nature of fashion, I think it’s also a recognition of Muslims’ growing global buying power. The fashion industry is finally seeing Muslims as consumers.

From my research, I’ve learned that the mainstream Western fashion industry’s embrace of Muslims as consumers has had negative consequences. Independent Muslim designers are being pushed out by fast fashion brands that can make their products quickly and at significantly cheaper prices. Many of the clothes sold by fast fashion brands like H&M are produced by Brown Muslim women in Indonesia and Bangladesh who work in unsafe work environments at low wages. Mainstream fashion advertisers have slowly begun to use Muslim models who regularly cover in their marketing campaigns. However, these models are primarily young, thin, visibly able-bodied, light-skinned, and non-Black. I cannot deny the importance of positive representation of Islam for young Muslim children’s self-esteem, especially considering the rise of anti-Muslim, which disproportionately affects visibly Muslim women. However, these advertisements reproduce the image of Islam as a “Brown” religion, contributing to the marginalization of Black Muslims. They also uphold Eurocentric beauty standards, leaving many Muslim women outside the realm of fashion.

The new focus on modesty in the mainstream Western fashion industry is mirrored by an uptick in scholarship about Muslim women’s dress that focuses on Muslim women outside of MENA. While I have been happy to see the decline of veil historiographies, which dominated the field of Muslim dress studies in the 1980s and 1990s, I am disappointed that the scholarship still privileges women living in Muslim-majority countries, including Turkey, Indonesia, and Iran. When Muslims living as religious minorities are discussed, race and racial difference are often ignored. The United States provides a unique case study because there is no racial or ethnic majority among Muslims, but there is a clear racial hierarchy in terms of defining Muslim authenticity. Despite Black Muslim women, specifically African-American women associated with the Nation of Islam and the Imam W. Deen Mohammed community, making it “cool” to cover as early as the 1920s and creating and building a fifty-year old fashion industry, they’ve largely been ignored by scholars. I hope to correct that.

Yomna Elsayed holds a PhD in communication from the University of Southern California. In her research, she examines the interplay of popular culture, social change and cultural resistance. Her dissertation examined how popular culture mechanisms, such as humor, music and creative digital arts, can be utilized tosustain social movements all while facilitating dialogue at times of ideological polarization and state repression.

Nabil Echchaibi is chair of the department of media studies and associate director of the Center for Media, Religion and Culture at the University of Colorado Boulder. His research and teaching interests include religion, popular culture, postcolonial and decolonial theory, and Islamic modernity. His work has appeared in various journals and book volumes. His opinion columns have been published in the Guardian, Forbes Magazine,Salon, Al Jazeera, the Huffington Post, Religion Dispatchesand Open Democracy.

Kayla Renée Wheeler is an Assistant Professor of African American Studies and Digital Studies at Grand Valley State University. Currently, she is writing a book on contemporary Black Muslim dress practices in the United States. The book explores how, for Black Muslim women, fashion acts a site of intrareligious and intra-racial dialogue over what it means to be Black, Muslim, and woman in the United States. She is the curator of the Black Islam Syllabus, which highlights the histories and contributions of Black Muslims. She is also the author of Mapping Malcolm’s Boston: Exploring the City that Made Malcolm X, which traces Malcolm X’s life in Boston from 1940 to 1953.