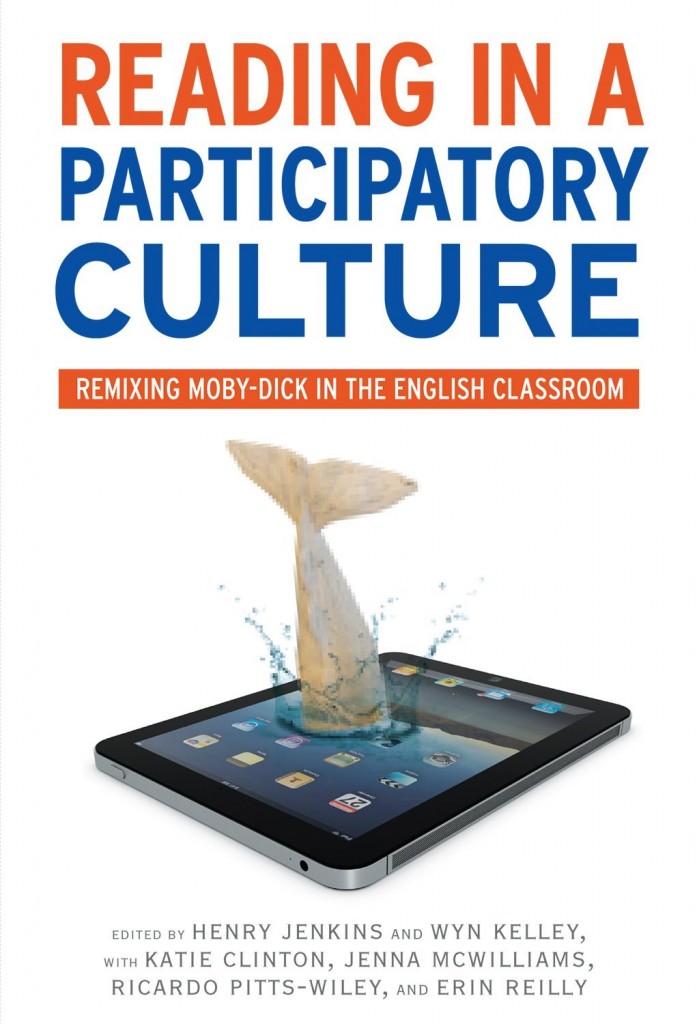

There She Blows! Reading in a Participatory Culture and Flows of Reading Launch Today

/

Today marks the release of not one but two closely related New Media Literacies publications. The first is a new print book, Reading in a Participatory Culture: Remixing Moby-Dick for the Literature Classroom, which is being published by Teacher's College Press in collaboration with the National Writing Project. I have not seen the completed book yet myself, but we are told that they will starting shipping copies as of Feb. 22.

The second is Flows of Reading, a digital book, which I have developed with Erin Reilly,the Creative Director of the Annenberg Innovation Lab, and Ritesh Mehta, a PhD candidate in the Annenberg School of Journalism and Communication here at USC. Flows of Reading is online and freely accessible, so check it out here.

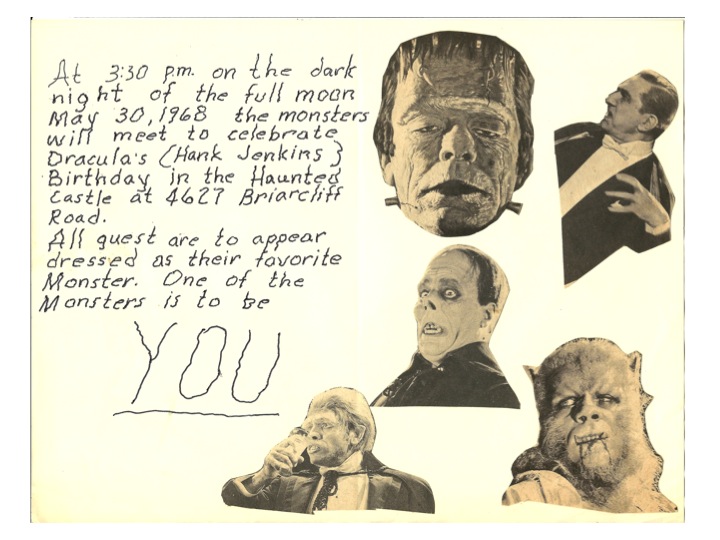

This project started back when I was at MIT and these two release represent the culmination of more than six years of work. We tell part of the story in the opening chapter of the book, which you can read here. Here's an excerpt:

At first glance, playwright, youth organizer, and community activist Ricardo Pitts-Wiley might seem like a peculiar inspiration for a book about digital media and participatory culture. Although Pitts-Wiley is enthusiastic about the potential of new media, much of his work is distinctly low-tech. He writes and produces remixed versions of such classics as Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein for a traditional venue: the community stage.

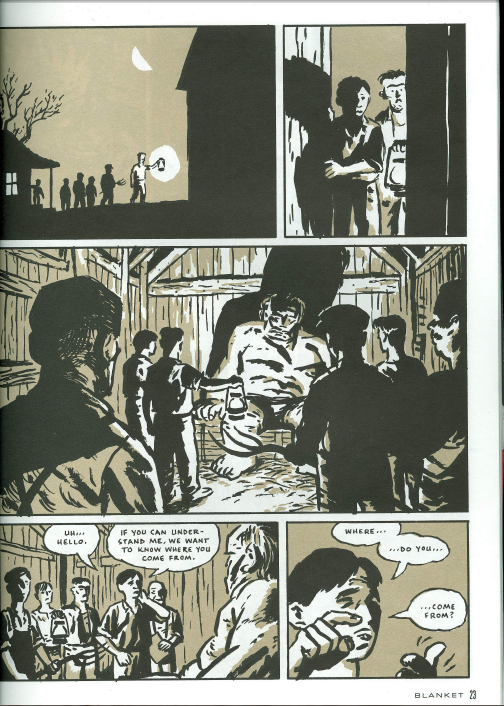

But something magical—something participatory—happens on that stage. First, his plays’ universal themes are seasoned with immediacy, with issues that resonate with his community. His play Moby-Dick: Then and Now, for example, intermingles the themes of Captain Ahab’s obsessions, his fatalism, his willingness to place his crew in peril, with contemporary urban gang culture. In Pitts-Wiley’s retelling, Ahab becomes Alba, a teenaged girl whose brother has been killed by a “WhiteThing” a mysterious figure for the international cocaine cartel; she devotes her life to finding, and killing, those responsible for her brother’s death.

In Moby-Dick: Then and Now, Pitts-Wiley chose not simply to revise the story, but to incorporate aspects of Melville’s version in counterpoint with Alba’s quest for vengeance. As the young actors pace the stage, telling their story in contemporary garb, lingo, and swagger, a literal scaffold above their heads holds a second set of actors who give life to Melville’s original tale. The “then” half of the cast are generally older and whiter than the adolescent, mixed-race “now” actors. The play’s meaning lies in the juxtaposition between these two very different worlds, a juxtaposition sometimes showing commonalities, sometimes contrasts.

Reading in a Participatory Culture reflects an equally dramatic meeting between worlds. Project New Media Literacies emerged from the MacArthur Foundation’s ground-breaking commitment to create a field around digital media and learning. The Foundation sought researchers who would investigate how young people learned outside of the formal educational setting–through their game play, their fannish participation, “hanging out, messing around, and geeking out” (Ito et al. 2010). The goal was to bring insights drawn from these sites of informal learning to the institutions—schools, museums, and libraries–that impact young people’s lives. Right now, many young people are deprived of those most effective learning tools and practices as they step inside the technology-free zone characterizing many schools, while other young people, who lack access to these experiences outside of school, are doubly deprived because schools are not helping them to catch up to their more highly connected peers.

Project New Media Literacies—first at MIT and now at USC–has brought together a multidisciplinary team of media researchers, designers, and educators to develop new curricular and pedagogical models that could contribute to this larger project. Our work has been informed by Henry Jenkins’ background as a media scholar focused on fan communities and popular culture and by the applied expertise of Erin Reilly, who had previously helped to create Zoey’s Room, a widely acclaimed on-line learning community that employs participatory practices to get young women more engaged with science and technology. Our team brought together educational researchers, such as Katie Clinton, who studied under James Paul Gee, and Jenna McWilliams, who had an MFA in creative writing and teaching experience in rhetoric and composition, with people like Anna Van Someren, who had done community-based media education through the YWCA and who had worked as a professional videomaker. Flourish Klink, who had helped to organize the influential Fan Fiction Alley website, which provides beta reading for amateur writers to hone their skills, and Lana Swartz who had been a classroom teacher working with special need children, also joined the research group. And our development and field testing of curricular resources involved us in collaborating both with other academic researchers, such as Howard Gardner’s Good Play Project at Harvard, with whom we developed a casebook on ethics and new media, and Dan Hickey, an expert on participatory assessment at Indiana University. We also worked with youth-focused organizations such as Global Kids, with classroom teachers such as Judith Nierenberg and Lynn Sykes in Massachusetts, and Becky Rupert in Indiana, who were rethinking and reworking our materials for their instructional purposes, and with scholars such as Wyn Kelley who had long sought new ways to make Melville’s works come alive in classrooms around the country.

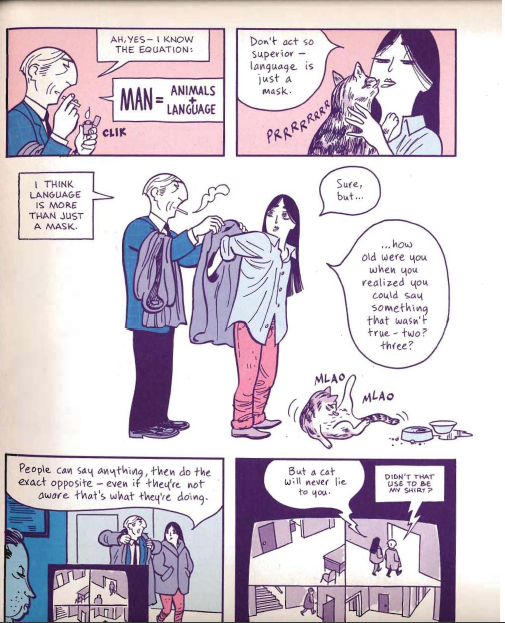

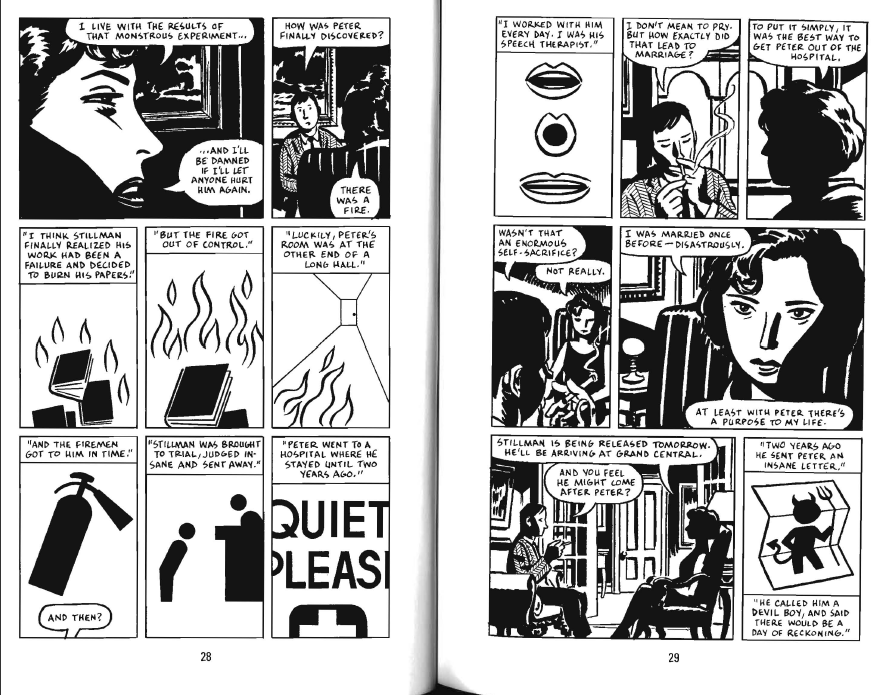

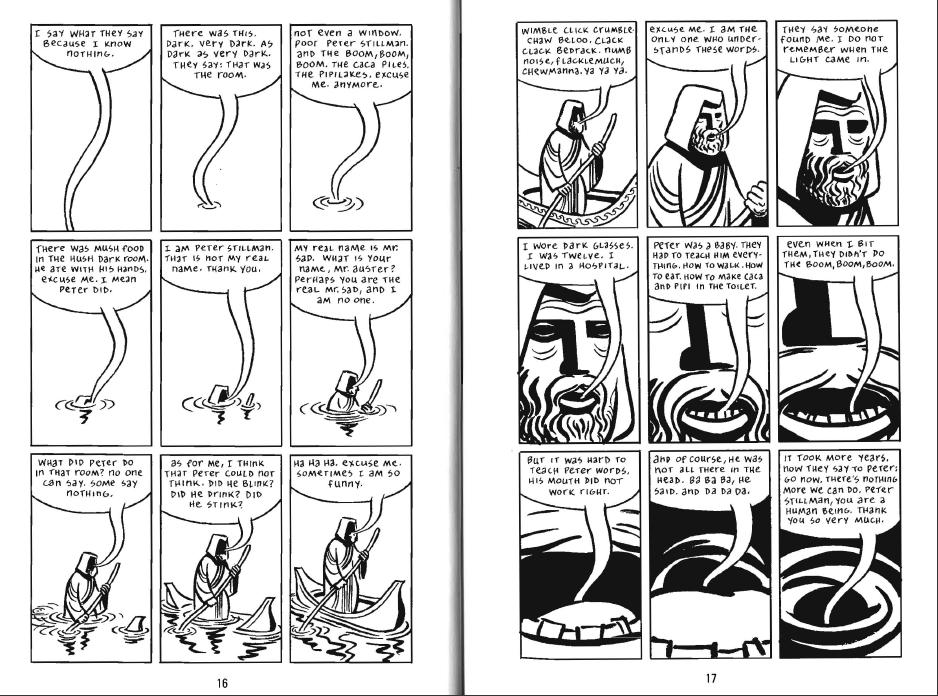

Reading in a Participatory Culture is targeted primarily at educators (inside and outside formal schooling structures) who want to share with their students a love for reading and for the creative process and who recognize the value of adopting a more participatory model of pedagogy. Our approach starts with a reconsideration of what it means to read, recognizing that we read in different ways for different goals and with different outcomes depending on what motivates us to engage with a given text. Literary scholar Wyn Kelley, Theater director/playwrite Ricardo Pitts-Wiley, actor Rudy Cabrera, and myself, writing as a fan and media scholar, each describe our complex and evolving relations with Moby-Dick, and encourage teachers and students to reflect more about their own experiences as readers. We use the idea of remix as a central concept running through the book, exploring how Pitts-Wiley remixed Moby-Dick, how Herman Melville remixed many elements of 19th century whaling culture, how other artists have remixed Melville's work through the years, and what it might mean for students and fans to engage creatively rather than simply critically with literary and media texts. Along the way, we provide a fuller explanation and assessment of what worked as we moved towards a more participatory culture oriented approach to teaching classic literary texts in the high school classroom.

Here's a few early responses to the book:

"In Reading in a Participatory Culture, Media Studies meets the Great White Whale in the English Classroom. This book is one of the most exciting and breathtaking works on English education ever written. At the same time it is must reading for anyone interested in digital media, digital culture, and learning in the 21st Century." — James Paul Gee, Mary Lou Fulton Presidential Professor of Literacy Studies, Arizona State University, and author of The Anti-Education Era

''An inspirational approach to democratizing the cultural canon and restoring classrooms to expansive educational purposes grounded in a participatory ethos. It explains in clear, accessible, and practically informative terms the New Media Literacies philosophy of reading and writing to prepare today's students for the world they must build -- together, collaboratively -- tomorrow. Reading in a Participatory Culture provides rich descriptions of experiences and perspectives of readers and writers, teachers, and learners who understand Moby-Dick as itself an instance of cultural remix and, in turn, a living creation to be remixed by all who take delight in it -- especially those who can come to take delight in it by being introduced to it as part of their education.'' -- Colin Lankshear, Adjunct Professor, James Cook University, Australia

Flows of Reading takes this process to the next level. We have created a rich environment designed to encourage close critical engagement not only with Moby-Dick but a range of other texts, including the children's picture book, Flotsam; Harry Potter; Hunger Games; and Lord of the Rings. We want to demonstrate that the book's approach can be applied to many different kinds of texts and may revitalize how we teach a diversity of forms of human expression. We look at many different adaptions and remixes of Moby-Dick from the films featuring Gregory Peck and Patrick Stewart as Ahab to MC Lar's music video, "Ahab" and Pitts-Wiley's Moby-Dick: Then and Now stage production to works that evoke Moby-Dick less directly, including Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan and Battlestar Galacitca's "Scar."

We share videos produced by the Project New Media Literacies team dealing not only with Moby-Dick but a range of cultural practices, including cosplay, animation, graffiti, and remix in music, but we also share many other clips, including a great series of videos on fan bidding produced by the Organization for Transformative Works and others produced by the Harry Potter Alliance. Altogether, there are more than 200 media elements incorporated into Flows of Reading.

We share classroom activities which were part of the original curriculum and we share "challenges" produced using our new PLAYground platform. The PLAYground platform is designed to allow teachers and students alike to produce and share multimedia "challenges" and to remix each other's work for new purposes and contexts. Think of it as Scratch for culture rather than code. In this case, it allows us to take the participatory pedagogy approach to the next level: this is not simply a book or a multimedia experience teacher's consume; it is a community of readers within which they can participate and we are creating a space where they can make their own contributions to this project.

This digital book was built using Scaler, a project of the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture at USC, and we are sharing the clips through Critical Commons, another USC initiative, which is intend to promote fair use of our shared culture for academic and creative purposes. We see this project as one which fuses traditional approaches to literature instruction with ideas drawn from Cultural Studies and Media Literacy, and we hope that the project provokes others to think about what can be learned at the intersection between high and popular culture.

And we also are using this project to explore how a classic work by a "dead white male writer" can contribute to multicultural education. Pitts-Wiley argues that Moby-Dick is already a multicultural work: as he explains, "everyone was already on that boat!" but we also show many different strategies for bringing alternative perspectives to bear on the book -- from a discussion of how artists and critics have responded to the absence of well-developed female characters in Moby-Dick to an exploration of contemporary Maori culture inspired by what Melville tells us about Quequeg's background. Along the way, we consider everything from the history of white appropriation of black music to the ways that Japanese and American subcultures build community and identity through cross-cultural borrowings.

Finally, we have some sections which deal directly with the representation of violence in literary and popular culture texts, recognizing that anxieties about media violence are concerns that teachers regularly must confront in their classrooms. We hope that you will check out Flows of Reading and even more so, we hope that it offers practical models and resources that educators may use to remodel how they teach Moby-Dick and other texts in their curriculum.

This project remains a work in progress. There are still some elements we hope to add or fix in the coming weeks, but it is now open to business, thanks to the hard work of Erin Reilly, Ritesh Mehta, and the other members of their team. (See the acknowledgements section in the digital book itself.)

Check it out. Participate. Spread the word. Share your insights with us.