Let Us Now Praise Famous Monsters: A Conversation (Part One)

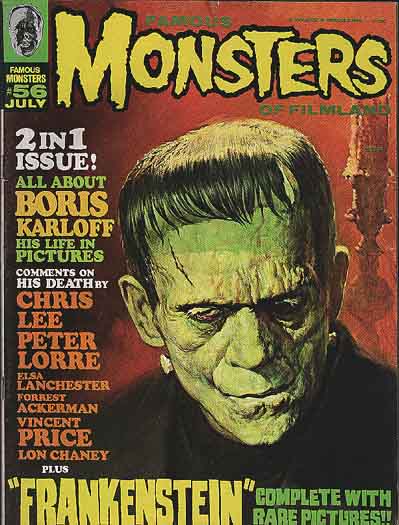

/This December, a new academic publication, The Journal of Fandom Studies (senior editor: Katherine Larsen), debuted, which should be of interest to some of my regular readers. The very first issue focuses on Famous Monsters of Filmland and its editor, Forest K. Ackerman. So much work in fan studies has dealt with science fiction fandoms, yet there's much we do not know about the "monster fan culture" of the 1960s and 1970s. As this issue suggests, digging into old monster magazines gives us a rich glimpse into the participatory culture of the period, including a range of material practices (such as model building, make-up and costume production, and Super 8 filmmaking) that have so far received limited attention by academics. Monster fan culture gives us a glimpse into what was at the time a predominantly male fan community, though, as we will see, there's also some important dimensions of female fan history to be reclaimed from the margins of this publication. And, we soon discover that Ackerman was not only a model for today's "fan boy auteur" but he also had a strong commitment to the politics of diversity and social acceptance, not exactly values we associate with American popular culture of the period.

I was honored to be asked to be a respondent for this issue, and in doing so, I ended up writing a heavily autobiographical essay about my own memories of being a preteenage monster fan during the 1960s. I am sharing the opening of my essay below in hopes that it may entice you to track down this issue. I invited the editor of this special issue, Matt Yockey, and the other contributors to participate in an informal online conversation, exploring their own relationships with the topic, and also suggesting some of the ways their work might help us to further broaden the domain of fan research.

I was honored to be asked to be a respondent for this issue, and in doing so, I ended up writing a heavily autobiographical essay about my own memories of being a preteenage monster fan during the 1960s. I am sharing the opening of my essay below in hopes that it may entice you to track down this issue. I invited the editor of this special issue, Matt Yockey, and the other contributors to participate in an informal online conversation, exploring their own relationships with the topic, and also suggesting some of the ways their work might help us to further broaden the domain of fan research.

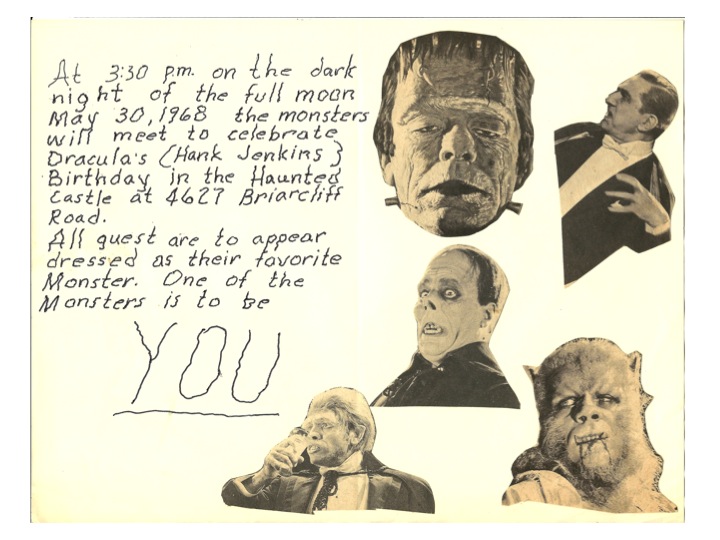

I cherish this invitation to my tenth birthday which my mother carefully and lovingly packed away with other artifacts of my childhood. The text, written in a quivering scrawl associated with old horror film posters, was accompanied by photographs of Boris Karloff’s Monster, Bela Lugosi’s Dracula, Lon Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera, Frederic March’s Hyde, and oddly, given my own strong preference for Lon Chaney Jr., Oliver Reed’s werewolf. The pictures had been cut from the pages of Famous Monsters of Filmland, almost certainly by my mother’s hands, given how precise the borders are, and then, attached with Elmer’s Glue, under my instructions, onto typing paper. The invitations were reproduced using a crude home photocopier machine my father used for his work, and then mailed to the other boys in the neighborhood.

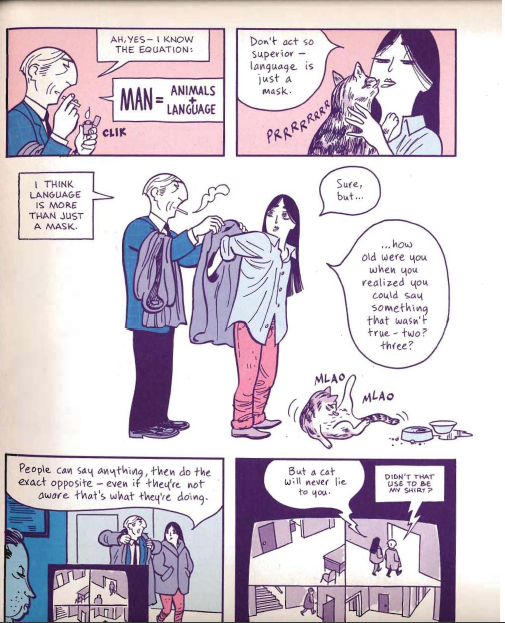

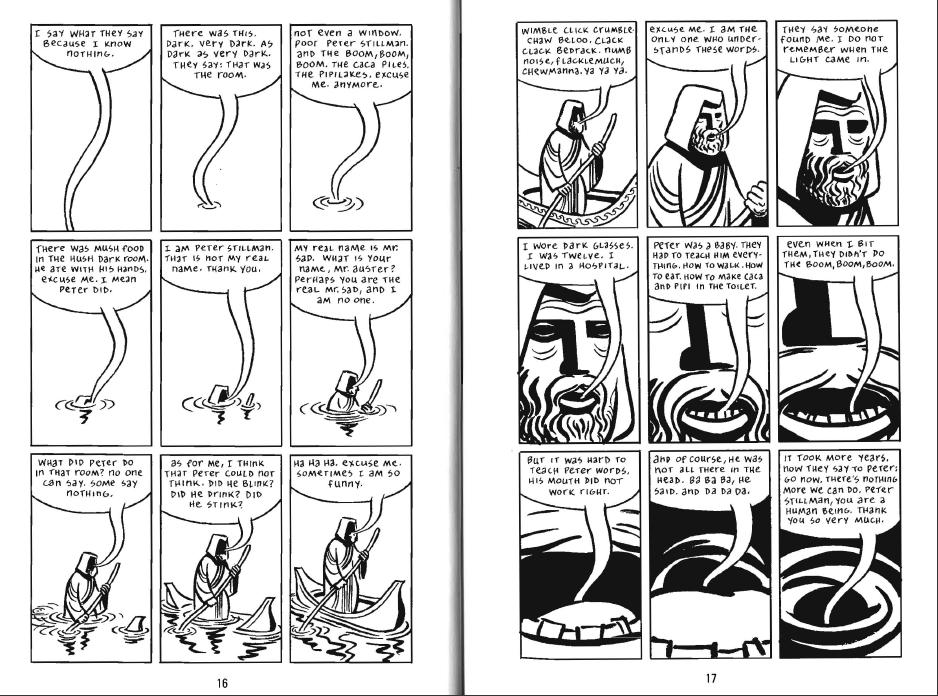

I dug the invitation out of storage recently when I returned from seeing “The Art of Tim Burton” exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Amidst concept art and film props, the exhibit devoted a room to his juvenaila, including a childhood sketch of the Creature of the Black Lagoon (mostly likely drawn from the Aurora monster model) and stop motion home movies (inspired by Ray Harryhausen). I was most taken with a collage (image 2), which mixes Burton’s own hand-drawn renderings of Frankenstein’s Monster, the Phantom of the Opera, and various space aliens, with pictures, including Lugosi’s Dracula, King Kong, and this time, appropriately, Lon Chaney Jr.’s Wolfman, almost certainly cut from Famous Monsters. Burton chose Lugosi, his face partially wrapped by his cape, where-as I went with an image where the vampire’s hands are clutched, ready to strike an unsuspecting victim, but both were part of the image bank we shared with so many other boys and girls, around the country, growing up in the mid-1960s.

Burton and I were born a little over two months apart, though his Burbank and my suburban Atlanta were on the opposite ends of the country. What we shared -- with a good chunk of our generation -- was a series of powerful cultural influences, as described in the LACMA exhibit’s accompanying coffee table book:

“He revered the legendary Vincent Price and identified with such maestros of classic horror as Lon Chaney Sr. and Jr., Boris Karloff, Peter Lore, and Bela Lugosi....He was swept up by the magic of the stop-motion animation of Ray Harryhausen’s animated sequences and the unique color pallete of Basil Gogo’s illustrations on the covers of Famous Monsters of Filmland magazines (one of the few publications he avidly read).” (Frey, Gallo, and Kempf, 2009, p. 8)

For all our self perceptions of eccentricity, Tim Burton and I had more or less the same childhood. We read the same magazines, watched the same movies, admired the same artists, and fetishized the same images. As Bob Rehak writes in this issue, “Facilitated by Famous Monsters and shared by a subculture of baby boomers in their preteen and teenaged years, the constructive activities of 60s horror fandom laid both a generational and physical groundwork for today’s transformative, franchised, materialized media culture.”...

I read these historical accounts from the perspective of someone who, unlike the other authors, was part of the 1960s monster culture they are seeking to reconstruct. This is not to say my account is somehow more “authentic” or “unmediated” than theirs. As Erica Rand (1995) has suggested, we selectively rewrite our personal narratives about our childhoods to reflect our adult conceptions of ourselves, creating an aura of personal inevitability rather than reflecting the contingency of emerging identities. What we and our parents chose to box and save are not necessarily any more a part of who we are than those many things that were tossed in the trash. The LACMA curators were no doubt drawn to those childhood artworks suggesting the gothic sensibility we associated with Burton’s films; I am drawn to childhood artifacts which reflect my subsequent academic interests in film history and fan culture. All of these accounts involve acts of interpretation and speculation, whether recovering the perspectives of Ackerman’s young fans from the photographs and letters in Famous Monsters or reconstructing my ten year old self from fading memories and yellowing party invites. So, I am writing this first person account to add another layer to our understanding of the period’s fan sensitivities and subjectivities.

As a starting point, we might add collage art to the mix of creative and performative activities, including model-making, super 8 filmmaking, costuming and make-up, that grew up around Famous Monsters. Cutting out and gluing down pictures to create a birthday party invitation may seem pretty banal -- not as transgresive as writing a homoerotic fan story or as transformative as posting a political remix video on YouTube. But, these material practices embody a similar expectation that consumers have the opportunity and right to meaningfully reshape their culture.

The fact that my parents sanctioned this bit of appropriation and remixing tells us something about Famous Monsters’ cultural status: my parents would not have allowed me to cut pictures from books or encyclopedias, they would happily allow me to cut pictures from old catalogs or newspapers, and magazines fell into a space in between -- National Geographic or Hightlights (no), Famous Monsters (yes). The growing accessability of photocopying (first prototyped in 1959 and introduced to home consumers in the mid-1960s) supported the easy reproduction of such images, paving the way for the DIY zine culture Stephen Duncombe (1997) documented. Such cut and paste collages would become characteristic of the 1980s punk and 1990s riot grrl zines, for example. These practices also extend a much older history of children’s scrapbooking, a practice, as historians (Tucker, Ott, and Buckler, 2006; Garvey, 2004) note, that has often mixed personal (family photographs, drawings) and mass produced images (magazines and newspaper clippings).

The overlap between Burton and my respective choices reflects the degree to which Famous Monsters helped define a canon of works its most hardcore readers were expected to know. The images we selected were shared culture (in that Burton and I draw on almost identical repertoires) and personal culture (in that Burton and I would have no doubt had different personal preferences -- my strong identification with Dracula, his fascination with Vincent Price and giant Japanese monsters). The magazine helped to set a syllabus of sorts for my adolescent efforts to educate myself about the history of American movies (and still informs my dvd collecting). I can draw a direct link from Famous Monsters to my decision to focus my Seventh Grade term paper, several years later, on the history of American movies. My father used to joke that I had been rewriting that term paper throughout my educational and professional life. My graduation from an elementary school monster movie buff to an undergraduate film snob was mirrored by the fact that George Ellis, the fright host for the Atlanta market, also owned the Film Forum, one of the city’s two major retro houses.

As Kevin Heffernan (2004) documents in Ghouls, Gimmicks and Gold, the Universal monster movies had been part of the large package of “Shock Theater” Screen Gems sold to television stations in the 1950s and still in active use on second tier local stations in the 1960s. After school, my friends would race home to check out which movies were playing, staying in doors if it was one featured in Famous Monsters, and otherwise going outside, often to play act those very same monster movies. At ten, we were not allowed to stay up for the “Friday Night Frights”, except in the summer time or over Christmas break, and then, often, with the carefully negotiated stipulation (shared by many of the neighborhood households) that we could stay awake only until we got to see the monster in action. This rule, designed to avoid conflicts over bedtimes, actually resulted in endless quiblings over whether a shadow or a movement in the branches really counted or in the case of The Wolfman, whether Lawrence Talbott counted as a monster before the moon turned full. As David Bordwell (2011) has noted, the tendency of vintage film audiences to show up when they could and watch through until the point where they entered the theater surely complicates claims about narrative structure and closure. Something similar could be said of my childhood viewing practices, which put such a strong emphasis on the monster’s first appearance and meant that we almost never saw any form of containment. Much like the superheroes, who occupied our imagination around the same time, the neighborhood kids could have told you the primary “powers” and vulnerabilities of each monster (Dracula could transform into bats or fog and command wolf packs; he could be destroyed by a stake to the heart, by cutting off his head, by being exposed to sunlight), but not the plot of any particular film.

Our love for “classic” horror movies gave us a certain distinction among our classmates, many of whom raced home from school to watch Dark Shadows. We had a running battle around the school lunch table over the relative merits of Lugosi’s Dracula (never Christopher Lee’s) and Dark Shadow’s Barnabas Collins. Tom Patterson, sometimes friend, sometimes rival, held his own monster birthday party a few months later, adopting the persona of Collins, as much to cross my tastes as anything else. Ackerman’s magazine fostered a immediate and personal link between his young readers and the grand old men who had helped to create the monster movies decades earlier. When I learned that Lon Chaney Jr. was struggling with cancer, I sent him a hand drawn get well card and received a photograph of the Wolf Man, signed with his own quivering hand....

Famous Monsters contained a wealth of information about these old films and the people who made them, but it was above all a picture magazine, and our favorites often reflected what we imagined from those images. I had seen few of the movies represented on the birthday invitation. For example, I had not seen the original Universal Dracula by age ten; I knew the character almost entirely from the magazine, the Aurora monster models, and my Famous Monsters Speak record. Several years later, I saw the 1930 Bela Lugosi film and found it surprisingly dull. I was even more frustrated (and bored) by my aborted attempt to read Bram Stoker’s novel. The blood curdling account of Dracula in Famous Monsters, much like The Princess Bride, contained only the “good parts”. So, the Dracula I loved and admired was largely a product of my own imagination, what I extrapulated from and mapped onto the stills Ackerman published.

Matthew, perhaps you can get us started by sharing how this special issue focused on Famous Monsters of Filmland came about.

Matt: This project began to percolate in the fall of 2007. I had just moved to southern California and visited Ackerman at the “mini-Ackermansion” during one of his Saturday open houses. I lingered after the official visiting hours were over and found that, with just me as his audience, Ackerman wanted to talk about his life - not just his work on FM or his life as a fan, but his family history, his relationship with his brother, etc. This first conversation quickly evolved into regular visits with prepared questions. Over the course of six months I accumulated about 20 hours of recorded conversation. At the same time I began to purchase 1960s-era issues of FM on Ebay with the idea of writing something scholarly about FM, as this was a subject near to my heart and which had been almost completely overlooked in academia. Around this time, I met you for the first time and seeing an Aurora model kit in your office felt like a bit of serendipity. This led to the SCMS panel with you, Mark, and Natasha, which was received so positively that finding a home to publish this work seemed the logical and inevitable next step. In another bit of serendipity, these essays crossed paths with Katherine Larsen, who was very receptive to the idea of an FM-theme for the debut issue of The Journal of Fandom Studies.

As I note in my essay, there’s a certain generational difference in experience represented within this group. I was a first generation Famous Monsters fan reading the magazine growing up in the 1960s, where-as most of you are quite a bit younger. How did each of you first encounter the magazine?

Matt: I have a vivid memory of being 4 years old in 1970 and seeing FM #80 at the local supermarket. The cover image was from Beneath the Planet of the Apes and I was absolutely transfixed. My aunt, whom I was with, refused to buy it for me and I had to wait a painfully long time before I actually purchased my first issue (#95 in late 1972). I loved FM but could only afford an issue every so often. I would look longingly at the gallery of back issue covers in each issue and wish I could have them all. It was a longing matched by my desire to see many of the films featured in every issue. Reading FM directed my weekly investigation of the latest issue of TV Guide to see if any of these films were going to be broadcast on the local station that had a Friday night horror show.

Bob: Matt and I are the same age, and my first encounter with Famous Monsters and subsequent experience of Monster Culture are similar to his. I came across FM at an Ann Arbor comic book store called the Eye of Agamotto, on a rack with other Warren publications such as horror comics Creepy and Eerie, and “mature” content like National Lampoon and Heavy Metal. At 9 or 10 I was too young to be drawn to those magazines, but FM, which my parents indulged me in buying, formed the nexus of my love of monster movies new and old, which I took in both at film society screenings on the University of Michigan campus, and on TV through creature features with hosts like “The Ghoul” on WKBD-50 and WJBK’s Sir Graves Ghastly. While I don’t remember the first issue of FM I owned, I do recall the first issue whose cover I found too frightening to look at directly: #111, October 1974, which bore a Basil Gogos portrait of Linda Blair in Dick Smith’s Exorcist makeup.

Mark: I’m a couple of years younger than Matt and Bob, and I didn’t really like FM that much or read it regularly, although I do have a strong memory of reading an issue while in the hospital (the negative associations are hard to shake). At the risk of sounding like a snobby little kid, I didn’t like FM’s irreverent tone and all the pun-based captions, although I did wear a T-shirt printed with an FM cover on the first day of third grade. Right before the class recited the Pledge of Allegiance, the teacher looked over at me and said “everyone put your hands over your monsters” (not surprisingly, he was one of my favorite teachers). Around that age, I was more drawn to books like Ed Naha’s Horrors from Screen to Scream and William Everson’s Classics of the Horror Film than to FM. My parents--my dad in particular--were very indulgent of my monster-mania, and would take me to see age-inappropriate films and let me stay up late on the weekends to watch old movies. I grew up in Omaha, where the local NBC affiliate broadcast Dr. Sanguinary’s Creature Feature every Saturday. I recall being absolutely livid when it was preempted by the appearance of Saturday Night Live.

I think in terms of generational difference in reception, by the time we were old enough to be interested in monster culture and horror films, there were simply more options to explore: more publications, more books, more toys, more ways to actually see some of the films. Undoubtedly, FM paved the way for this, but it may also be the reason my own response to FM was so cool. Interestingly, my partner, who is roughly a generation older than I am, has a big stash of FMs from when he was a kid.

Mark Hain is a PhD candidate in the Department of Communication and Culture at Indiana University, and is currently working on his dissertation, which is a historical reception study looking at star image and how audiences interpret and find use for these images, with a specific focus on Theda Bara.

Bob Rehak is an Assistant Professor in the Film and Media Studies Program at Swarthmore College. His research interests include special effects and the material practices of fandom.

Natashia Ritsma is a PhD candidate in the Department of Communication and Culture at Indiana University. Her research interests focus on documentary, experimental and educational film and television.

Matt Yockey is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Theater and Film at the University of Toledo. His research interest is on the reception of Hollywood genre films.