Lsst time, I shared some of my current thinking about the challenges of designing an "open-laptop exam" and the new approach we have sought to apply to my lecture-hall scale class on new media and culture this term. Today, I share the actual syllabus for the course and the ways we have set it up for the students.

A key thing to notice here is that we introduced the notion of new forms of learning from the very first day of class, making it part of the course content and not simply part of the course mechanics. We have also introduced assignments -- such as one around Wikipedia -- which focus students on how networked communities do work together to achieve shared goals, again in anticipation of what happens when we move into a more collective mode for the second part of the class. Our goal has been to be as explicit and transparent as possible about each element of the class design and to link it to the larger concepts this class seeks to explore. It might be harder to be this reflexive about the process in a different kind of subject.

Second, I designed the requirements to give students an increased sense of control over their performance in the first half of the class, when they are functioning primarily as individuals, by having multiple paths to success, and we have also designed the discussion sections and topics across the term to have an emphasis on the investigative process, so that when we turn to collective problem solving in the second part, they will already have worked in teams of various sizes to think through basic issues around digital culture which have a strong applied dimension. I plan to share some samples of these small group activities later in the term. So keep an eye on this blog.

I am reluctant to say too much about the class itself while it is still in process. But I will say that so far, we all seem to be having fun with this new approach and the students seem, if anything, less anxious than they had been under more traditional assignment structures. But, we are still in the more familiar, individualized portion of the class, and I do not yet know what happens when we make the shift at the mid-term, just a few weeks from now.

COMMUNICATION & TECHNOLOGY

ANNENBERG COMM 202 - FALL 2012

Monday & Wednesday, 2:00pm - 3:20pm

ASC G26 (The Auditorium)

INSTRUCTOR:

Professor Henry Jenkins

TEACHING ASSISTANTS:

Rhea Vichot

Andrew Schrock

Meryl Alper

CLASS OVERVIEW

This class is intended as an introduction to issues of media, technology, culture, and communication as read through the lens of contemporary debates concerning the Web and digital culture more generally. Each class session will explore a central question that has emerged from popular and academic responses to the ways our society has dealt with introduction of the Internet, with readings drawn from a range of sources including journalistic and scholarly writings and major policy statements and white papers.

We will start with a focus on your own experiences as part of a generation that has grown up in a world where digital media use -- and opportunities to participate in networked communication -- have been widespread. We will explore what impact these experiences have had on your styles of learning, your sense of privacy, and your social interactions with your peers.

From there, we will broaden our consideration to think about the process of media change, drawing examples from both the history of the Internet and from the history of earlier communications technologies (from the printing press to the telephone, photography, the phonograph, film, and television). In this unit, we will consider what factors shape the embrace or rejection of new technologies, whether change is even across segments of society or across different parts of the world, and whether new media has encouraged greater interests in forms of cultural and civic participation.

In the third section of the class, we will sharpen our focus to deal with specific sites of media change, especially those concerning the intersection between old and new media, including those concerning advertising, cultural production and distribution, news, and political debate. Here, we will consider two core concepts – “Web 2.0” and “Piracy,” both of which represent points of conflict between the interests of media companies and their publics.

COURSE DESIGN & LEARNING OUTCOMES

The design of this course has been very much shaped by its content. Research is suggesting some fundamental shifts in the way knowledge is produced in the digital era, having to do with the access of participants to small and large scale networks which collaborate and debate information together. As a consequence, this course progresses from students seeking to identify your own strengths as learners and participants within a digital culture towards students making contributions to a larger collective intelligence process.

For the first half of the course, then, you will be graded individually while during the second part, you will function as part of knowledge communities (small scale teams) which will be graded collectively based on their effectiveness at responding to more complex challenges. For the first part of the course, you will be expected to do each of the readings and be ready to share what you understood from them. For the second part, more reading is assigned each day than could be done by an individual student with the expectations that the teams will divide the labor appropriately to insure that each group has mastered the material. The teams will be able to rehearse their collaborative skills through discussion group activities across the term, each of which are designed to apply the course concepts to specific aspects of contemporary digital culture.

PARTICIPATION

Because this class is structured around inquiry and dialogue, students will be expected to attend class sessions and respond to questions from the instructor. We will be calling on students individually across the semester, so you need to come to class prepared to contribute, and we will be keeping records of who volunteers and how well you respond to the questions they are asked. This course is as much about teaching new ways of thinking as it is about conveying specific bits of content, so you need to be able to sharpen your ability to contribute to some of the central debates impacting contemporary culture.

READINGS

All course materials can be found on Blackboard. Many of these materials were originally published in digital formats, some of which take advantages of the specific affordances of the web, so students are strongly encouraged to read them online, and be selective about what materials they chose to print out in order to be environmentally conscious.

LAPTOP POLICY

You are expected to bring and use laptops, tablets, or other wireless devices during the class. While you are discouraged from doing non-class related activities that might distract you or your other students from the learning process, we will be actively deploying online resources throughout our discussion.

ASSIGNMENTS & GRADING

All assignments are due to your TA at the beginning of your discussion section. Your TA will explain the format and method for turning in your assignments in the first week’s discussion section. All assignments should include a list of citations (see Academic Integrity Policy below). You will receive graded feedback on your papers and graded scores on your exams. Students will automatically lose one point for each day the paper is late, unless arrangements have been made prior to the due date with your TA.

Fifty percent (50%) of the class grade will be based on individual performance (prior to the midterm exam) and fifty percent (50%) will be based on collective performance (after the midterm exam). Your final semester grade will be an average of the two letter grades derived from both columns below.

Semester Breakdown

First Half (8 Weeks) - Individual1. Participation in online forum (7 points + 3 additional)

2. Participation in class (10 points)

3. Attendance + participation in discussion section (7 points + 3 additional)

4. Autobiographical essay (5 points)

5. Reporting on Wikipedia (10 points)

6. Midterm Exam (20 points)

TOTAL POSSIBLE: 65 points

Second Half (7 Weeks) - Teams7. Collective Problem Solving (5 points per week for 4 weeks, 20 points total)

8. Collective Participation (10 points)

9. Final Exam (30 points)

10. Individual Reflection (5 points)

TOTAL POSSIBLE: 65 points

A+: 58 points or moreA: 55-57 pointsA-: 50-54 points

B+: 48-49 points

B: 45-47 points

B-: 40-44 pointsC: 35-39 points

D: 30-34 points

F: Under 30 points

First Half: Individual Performance

In the individual performance section, you may choose from a range of different mechanisms for acquiring points and thus demonstrating your mastery over the course materials. This formula allows you to play to your strengths as a learner and to focus your energy in ways which allow you to best demonstrate what you know.

1. Participation in online forum (Up to 10 points)

Every week, you will be expected to use Blackboard's Forum to share a core question or thought that emerges from the assigned readings. These questions can be a paragraph or so and informal, but they are intended to help the instructors better understand how the students are relating to the class materials and content. You will get a Check if you make a substantive comment, which poses questions about the core premise of the readings, which uses outside examples to expand our understanding of the core concept, or otherwise shows creative and critical engagement with the course content. In rare cases, you may receive a plus if your work goes well beyond what is typical for the class on a given assignment. You will not receive any points if the work turned in is perfunctory. You will be expected to post seven times prior to the midterm exam, so most students will receive 7 points on this assignment, but you may receive up to 10 points in cases of exceptional performance.

2. Participation in Class (Up to 10 points)

Our regular meeting sessions will be a mixture of lecture, screening, and discussion. You are expected to attend and be prepared to participate, and the instructor will be calling periodically on each student throughout the term. You will receive points based on your ability to meaningfully contribute, whether voluntarily or when called upon.

3. Attendance and Participation in Discussion Sessions (Up to 10 points) The Discussion Session is a central element in the class and attendance is mandatory. Regular attendance at all sessions will gain 7 points; students may acquire up to 3 additional points if they actively participate in the class discussions. Students lose one point for each class session they miss.

4. Autobiographical essay (Up to 5 points)

The opening sessions of the class explore the debates around the issue of how new media technologies and practices have shaped the current generation of students with some writers speaking of “digital natives” who have become very adept at navigating the online world and others dismissing the “dumbest generation” for its lack of familiarity with more traditional kinds of print literacy. You should respond to one of the essays we’ve read or videos we’ve watched in class which stakes out a position on this issue. You will draft a short (5 page) essay exploring their own relationship to new communication technologies and practices. There are many valid ways of approaching this assignment. You might describe a particular program you use regularly and how it impacts your day to day activities. You might trace your evolving relations to computers. You might describe a specific activity that is important to you and talk about the range of technologies you deploy in the pursuit of these interests. In each case, the paper is going to be evaluated based on the ways you deploy your personal experience to construct an argument about the nature of new communication technologies and practices and their impact on everyday life. The more specific you can be at pointing to uses of these technologies, the better. You do not need to make sweeping arguments about "Today's Society" but you do need to argue how particular technologies and practices impacted specific aspects of your own experience. For some sample essays that achieve our goals for this assignment, see:

Henry Jenkins, "Love Online" http://www.technologyreview.com/web/12979/

Hillary Kolos, "Bouncing Off the Walls" http://henryjenkins.org/2009/05/bouncing_off_the_walls_playing.html

Flourish Klink, "The Radical Idea That Children Are People" http://henryjenkins.org/2009/06/the_radical_idea_that_children.html

5. Reporting on Wikipedia (Up to 10 points)

Identify a Wikipedia entry that has undergone substantial revision. Review the process by which the entry was written and the debates which have surrounded its revision. Write a five-page essay discussing what you learn about the process by which Wikipedia entries are produced and vetted. How does the discussion and debate around the entry draw on the core principles of the Wikipedia community? Again, this paper is intended to combine research and analysis. You will be evaluated based on the amount of research performed, on the quality of the analysis you offer, on how you build off concepts from the readings and the lectures to help frame your analysis (including, ideally, direct references to specific readings), and on how well you understanding the nature of the new communications environment.

6. Midterm Exam (Up to 20 points)

The exam will be open-notes. It may include a mix of identification terms, short answer, and essay questions. The terms and essay questions will be selected from a list circulated in advance. The Midterm Exam will cover material from the first two units.

Revisions & Extra Credit

You will be allowed to revise ONE of the two essays to be considered for a higher grade. The paper must be turned in no later than two weeks after the original paper was returned. The grade will only be raised if the revisions substantively address one or more of the criteria for the paper's evaluation. Students who simply correct cosmetic or grammatical errors identified by the grader will not receive a higher score.

Second Half: Collective Performance

Following the midterm, students will be divided into teams organized around their discussion session. The teams will be assessed based on their collective performance on the assignments. The class is designed so most, if not all, of the synchronous work of the teams is done within regular course meeting times, minimizing the need for outside meetings. Teams are encouraged to experiment with tools such as Googledocs, Skype, and social media in order to coordinate their efforts beyond the regular sessions.

1. Collective Problem Solving (Up to 5 points per week, for a total of 20 points)

Each week, the teams will be asked to use the discussion section time to work through problem sets as a group, pooling your knowledge from the class and beyond in order to answer complex questions which you would not be able to address as individuals. The TA will function as a coach helping the team develop strategies for dividing up the problem and developing a coherent response in the hour devoted to the discussion session. Students teams can acquire up to 5 points each week based on the thoroughness, originality, clarity, and accuracy of their responses to the problems. We will work through four problem sets together in discussion section before students are asked to coordinate and collaborate in responding to the exam. You are expected to attend and participate actively in these sessions; you will not receive any point earned by the group in an activity on which you were absent from class.

2. Collective Participation (Up to 10 points)

Each team will gather a collective score based on their regular attendance and participation in the lecture and discussion sections. While the instructors called on individual students by name throughout the first part of the term, we will now be calling on teams. Each team should determine its own name and develop strategies for delegating responsibilities for answering questions. Teams can acquire up to 10 points based on their participation and class attendance.

3. Exam (Up to 30 Points)

Student groups will be given three questions at the beginning of lecture on Monday, December 3 and will be responsible for completing them by the end of lecture on Wednesday, December 5. It is expected that groups will use the Monday lecture slot to start planning (and possibly writing) their answers and the Wednesday lecture slot to finalize their answers. Groups are allowed (indeed encouraged) to work on the exams in-between the two lectures. The questions on the exam will resemble the questions groups will have worked on in section except that they will require that answers synthesize material from throughout the second half of the semester (though you are welcome to include material from the first half of the semester and/or outside sources). A collective score (up to 30 points) will be given to each team based on the thoroughness, originality, clarity, and accuracy of their responses. (Note: Students are allowed to *consult* with members from groups other than their own while working on the exam, but they must acknowledge all consultation, and groups must write original answers with cited sources. More specifics on permissible and impermissible collaboration will be provided with the exam).

4. Individual Reflection

For the remaining 5 points of the collective performance grade, students have two options. Individuals can choose either option and this is the only portion of the collective performance grade that students will be graded on individually. The instructors would prefer you choose the first option, but you will not be penalized for choosing the second option.

Option 1: Adam Kahn, a doctoral student at Annenberg, studies group collaboration and is interested in using COMM 202 in a research study he is conducting. For Option 1, all you have to do is fill out a few (no more than 4), brief (no more than 10 minute) surveys throughout the semester. These surveys are ungraded...by completing all of the surveys he administers, you will receive the full 5 points (you must complete all of them though to receive any points). To protect your confidentiality and grades, Professor Jenkins and the TAs will never see your responses to the survey. On the surveys, you will be identified only by your USC ID number. This will allow Adam to let the teaching staff know at the end of the semester that you have completed the surveys, but at the same time protect your anonymity, as Adam has no way to translate a USC ID number into your name. By participating in the surveys, you are also allowing Adam to associate your grades (again, identified only by USC ID number) with your survey responses.

Option 2: If you do not want to participate in the research study, you can write a 5 page paper comparing your experiences taking tests as an individual with taking tests as a group.

ATTENDANCE POLICY

Attendance at all lectures and discussion sections is expected and has been built into the grading of the class. In lecture, we will not take attendance per se, but if you are called upon and are not able to answer because you missed class, you will not receive points for that session. Flexibility for dealing with emergencies is built into this mechanics since there are multiple ways to gain the number of points required to make an A in the class.

For those assignments which require/allow collaboration, students are required to disclose all people who contributed to their process and identify all outside sources they drew upon in developing their answers. Failure to do so will be considered academic dishonesty.

SEMESTER SCHEDULE & READINGS

PART 1: LIVING AND LEARNING IN A NETWORKED CULTURE

Week 1, Day 1

Monday, August 27

Are You a Digital Native?

• No readings.

Week 2, Day 2

Wednesday, August 29

Is Google Making Us Stupid?

• Nancy Baym, "Making New Media Make Sense," Personal Connection in the Digital

Age (New York: Polity, 2010),

pp. 22-49.

• Nicholas Carr, "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" The Atlantic, August 2008. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/6868/

• Clay Shirky, “Does the Internet Make You Smarter?,” The Wall Street Journal, June 4 2010,

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704025304575284973472694334.html

Week 1 Discussion Section

Course Mechanics; Autobiographical Essays

Week 2, Day 3

Monday September 3

NOTE: NO CLASS. Today is Labor Day.

Week 2, Day 4

Wednesday, September 5

How Are Educators Responding to the Challenges of a Networked Culture?

• Screen: New Learners of the 21st Century

• Ilana Gershon, “Fifty Ways to Leave Your Lover,” The Breakup 2.0: Disconnecting over New Media (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010), pp. 16-49.

.Henry Jenkins et al, Confronting the Challenges of a Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century (MacArthur Foundation, 2006), http://digitallearning.macfound.org/atf/cf/%7B7E45C7E0-A3E0-4B89-AC9C-E807E1B0AE4E%7D/JENKINS_WHITE_PAPER.PDF

Week 2 Discussion Section: Would You Break Up Online?

Week 3, Day 5

Monday, September 10

What Does Learning Look Like in a Networked Culture?

•Henry Jenkins, “Spoiling Survivor,” Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: New York University Press, 2006), pp. 25-58

Week 3, Day 6

Wednesday, September 12

Do Youth Still Care About Privacy?

• danah boyd and Alice Marwick, “Social Steganography: Privacy in Networked Publics,” Presented at International Communications Association, May 28 2011, http://www.danah.org/papers/2011/Steganography-ICAVersion.pdf

Week 3 Discussion Section: Facebook and Privacy

NOTE: Paper 1 is due.

Week 4, Day 7

Monday, September 17

Is the Web Making Us Lonely?

• Stephen Marche, “Is Facebook Making Us Lonely?,” The Atlantic, May 2012, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/05/is-facebook-making-us-lonely/8930/

• Eric Klinenberg, “Facebook Isn’t Making Us Lonely,” Slate, April 19 2012, http://www.slate.com/articles/life/culturebox/2012/04/is_facebook_making_us_lonely_no_the_atlantic_cover_story_is_wrong_.html

• Sherry Turkle, “Does Technology Serve Human Purposes?,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, August 22, 24, 26 2011, http://henryjenkins.org/2011/08/an_interview_with_sherry_turkl.html, http://henryjenkins.org/2011/08/does_this_technology_serve_hum.html, http://henryjenkins.org/2011/08/does_this_technology_serve_hum_1.html

Week 4, Day 8

Wednesday, September 19

Should Schools Ban Wikipedia?

• Henry Jenkins, “What Wikipedia Can Teach Us About the New Media Literacies,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, June 26 2007, http://henryjenkins.org/2007/06/what_wikipedia_can_teach_us_ab.html; June 27, 2007, http://henryjenkins.org/2007/06/what_wikipedia_can_teach_us_ab_1.html

• Andrew Lih, "Community at Work (The Piranha Effect)," The Wikipedia Revolution (New York: Hyperion, 2009), pp. 81-132.

• Quora. “What does Jimmy Wales think when a university professor states not to cite Wikipedia as a source?” http://www.quora.com/Jimmy-Wales-1/What-does-Jimmy-Wales-think-when-a-university-professor-states-not-to-cite-Wikipedia-as-a-source

Week 4 Discussion Section: Wikipedia Mechanics

Week 5, Day 9

Monday, September 24

What Are We Using Mobile Media For? (Guest Lecture: Meryl Alper)

• “Pew Internet and American Life Project: Mobile” (2012) https://ca.edubirdie.com/blog/pew-internet-mobile Research highlights related to mobile technology in the US

• Jill Palzkill Woelfer and David G. Hendry (2011). Homeless young people and technology: Ordinary interactions, extraordinary circumstances. interactions, 18(6), 70-73.

• Chris Danielsen, Anne Taylor, and Wesley Majerus. (2011). Design and public policy considerations for accessible e-book readers. interactions, 18(1), 67-70.

PART 2: UNDERSTANDING MEDIA CHANGE

Week 5, Day 10

Wednesday, September 26

How Have Earlier Cultures Dealt with Media Change?

• Lynn Spigel, "Television in the Family Circle," Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992). pp. 36-72.

Week 5 Discussion Section: Advertising New Media

Week 6, Day 11

Monday, October 1

Why Do Interfaces Matter? (Guest Lecture: Adam Kahn)

• Vannevar Bush. “As We May Think,” Atlantic Monthly, July 1945, 101-108.

Week 6, Day 12

Wednesday, October 3

What Roles have Hackers Played in Defining Digital Culture? (Guest Lecture: Andrew Schrock)

• Doug Thomas, “(Not) Hackers: Subculture, Style and Media Incorporation,” Hacker culture (pp. 141–171). (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), pp. 147-171.

• Heather Brooke, “Inside the Secret World of Hackers,” The Guardian, August 24 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2011/aug/24/inside-secret-world-of-hackers

Week 6 Discussion Section: Hacking and Culture Jamming

NOTE: Paper 2 is due.

Week 7, Day 13

Monday, October 8

Why Does It Matter What We Call the “Web”?

• David Thorburn, “Web of Paradox,” The American Prospect, December 19 2001, http://prospect.org/article/essay-web-paradox

• Handout: Key Statements about the Nature of the Web

Week 7, Day 14

Wednesday, October 10

What Roles Does Participation Play in Contemporary Culture?

• Henry Jenkins, "Nine Propositions Towards a Cultural Theory of YouTube," Confessions of an Aca-Fan, May 28 2007. http://www.henryjenkins.org/2007/05/9_%20propositions_towards_a_cultu.html

.Lawrence Lessig, “REMIX: How Creativity Is Being Strangled By the Law,” in Michael Mandiberg (ed.) The Social Media Reader (New York: New York University Press, 2012), pp. 155-169.

Week 7 Discussion Section: YouTube’s Many Communities

Week 8, Day 15

Monday, October 15

What Can Science Fiction Teach Us About the History of Technology?

• Rebecca Onion, “Reclaiming the Machine: An Introductory Look at Steampunk in Everyday Practice,” Neo-Victorian Studies, Autumn 2008, http://www.neovictorianstudies.com/past_issues/Autumn2008/NVS%201-1%20R-Onion.pdf

Week 8, Day 16

Wednesday, October 17

Has Networked Culture Gone Global? (Guest Lecture: Alex Leavitt)

• Toshie Takahashi, “MySpace or Mixi? Japanese engagement with SNS (social networking sites) in the global age.” New Media & Society, May 2010 vol. 12 no. 3, 453-475. http://nms.sagepub.com/content/12/3/453

• Shaojung Wang, “China’s Internet lexicon: The symbolic meaning and commoditization of Grass Mud Horse in the harmonious society.” First Monday, January 2012, vol. 17 no. 1. http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/3758/3134

Week 8 Discussion Section: Review for Midterm

Week 9, Day 17

Monday, October 22

Midterm Exam

PART 3: THE WORLD WE LIVE IN

Week 9, Day 18

Wednesday, October 24

What Roles Do New Media Play in American Politics?

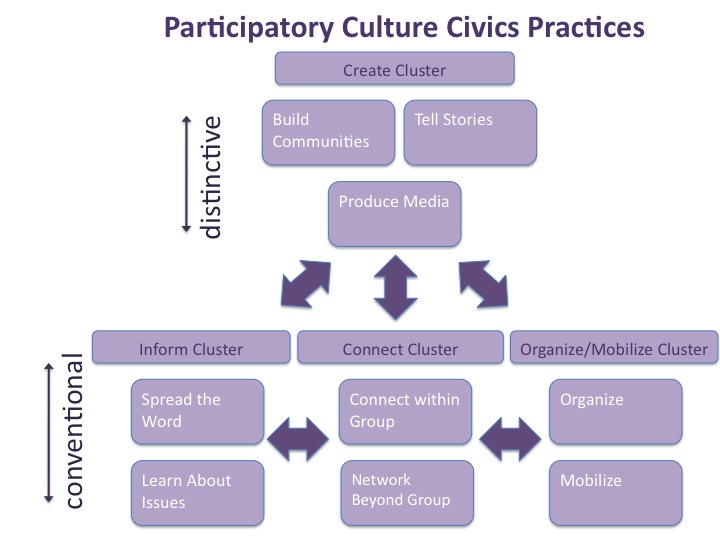

• Cathy Cohen and Joe Kahne, “Participatory Politics New Media and Youth Political Action,” Youth and Participatory Politics Network, 2011, http://ypp.dmlcentral.net/sites/all/files/publications/YPP_Survey_Report_FULL.pdf

• Ryan Lizza, “Battleplans: How Obama Won,” The New Yorker, November 17, 2008, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/11/17/081117fa_fact_lizza

• Daniel Kreiss, “Developing Technologies of Control: Producing Political Participation in Online Electorial Campaigning,” Paper presented on September 21, 2011 at the Oxford Internet Institute “A Decade in Internet Time” conference http://danielkreiss.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/kreiss_controltechnologies.pdf

Week 9 Discussion Session: Working Together in Teams

Week 10, Day 19

Monday, October 29

How Does Media Spread?

• Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green, “Why Media Spreads,” Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2013).

• danah boyd, “The Power of Youth: How Invisible Children Orchestrated Kony 2012,” Huffington Post, March 14, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/danah-boyd/post_3126_b_1345782.html

• Ethan Zuckerman, “Unpacking Kony 2012,” My Heart’s in Accra, March 8, 2012, http://www.ethanzuckerman.com/blog/2012/03/08/unpacking-kony-2012/

• James Gleick, “What Defines a Meme?” Smithsonian.com, May 2012, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/What-Defines-a-Meme.html

• Ilya Vedrashko, “A Site That Went Viral and the Numbers Behind It,” Hill Holliday Blog, http://www.hhcc.com/blog/2010/07/a-site-that-went-viral-and-the-numbers-behind-it/

Week 10, Day 20

Wednesday, October 31

How Generative are Online Communities? (Guest Lecture: Rhea Vichot)

• Mark McLelland, “‘Race’ on the Japanese internet: discussing Korea and Koreans on ‘2-channeru.’” New Media & Society, 2008, 10(6), 811 - 829.

• Gabriella Coleman, “Anonymous: From Lulz to Collective Action,” 2011, http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/tne/pieces/anonymous-lulz-collective-action

• Whitney Phillips, “The House That Fox Built: Anonymous, Spectacle and Cycles of Amplification,” Television and New Media, forthcoming.

http://hastac.org/blogs/whitneyphillips/2012/05/20/4chan-article-published-house-fox-built-anonymous-spectacle-and-cyc

• Michele Knobel & Colin Lankshear, “Online Memes, Affinities, and Cultural Production.” In M. Knobel and C Lankshear (Eds.), 2007, A Media Literacies Sampler. 199 - 228.

Week 10 Discussion Section: Tracking Viral Success

Week 11, Day 21

Monday, November 5

Have There Been Twitter Revolutions?

• Ethan Zuckerman, “The Cute Cat Theory Talk at eTech,” My Heart’s in Accra, March 8, 2008, http://www.ethanzuckerman.com/blog/2008/03/08/the-cute-cat-theory-talk-at-etech/

• Malcolm Gladwell, “Small Change,” The New Yorker, October 4, 2010, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell

• Evgeny Morozov, “Think Again: The Internet,” Foreign Policy, May/June 2010, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2010/04/26/think_again_the_internet

Week 11, Day 22

Wednesday, November 7

What is Web 2.0?

• Tim O'Reilly, "What is Web 2.0," O'Reilly Media, September 30, 2005, http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

• Jeff Howe, "The Rise of Crowdsourcing," Wired, June 2006, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/14.06/crowds.html

• Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green, “What Went Wrong with Web 2.0?,” Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2013).

• Geert Lovink, “Capturing Web 2.0 Before Its Disappearance,” Networks Without a Cause: A Critique of Social Media (London: Polity, 2012), pp.1-23.

Week 11 Discussion Section: Kickstarter as a Web 2.0 Company

Week 12, Day 23

Monday, November 12

What Will Be the Future of Advertising?

• Cory Doctorow, "The Branding of Billy Bailey," A Place So Foreign and Eight More

(San Francisco: Running Press, 2003), pp. 86-98.

• Daniele Sacks, “The Future of Advertising,” Fast Company, November 17, 2010, http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/151/mayhem-on-madison-avenue.html

• Campfire, True Blood - http://vimeo.com/8268162

• Weiden & Kennedy, Old Spice - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kg0booW1uOQ

• Burger King, Whopper Sacrifice - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxXxhEjnJA0

• Barbarian Group, Subservient Chicken (Burger King) -http://vimeo.com/16742192

• Hill Holiday, Mad Men + Newsweek - http://vimeo.com/44876203

Week 12, Day 24

Wednesday, November 14

Are Pirates a Threat to Media Industries?

• Nancy Baym, "The New Shape of Online Community: The Example of Swedish Independent Music Fandom," First Monday, May 16, 2007, http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1978/1853/

• William W. Fischer, "The Promise of New Technology,” Promises to Keep: Technology, Law and the Future of Entertainment (San Francisco: Stanford U. Press, 2004), pp. 11-37.

.Cory Doctorow, “Music: The Internet’s Original Sin,” Locus Online, July 4, 2012, http://www.locusmag.com/Perspectives/2012/07/cory-doctorow-music-the-internets-original-sin/

• “Artist Revenue Streams, The Future of Music Coalition, http://money.futureofmusic.org/

• “Piracy Online,” RIAA, http://www.riaa.com/physicalpiracy.php?content_selector=What-is-Online-Piracy

Week 12 Discussion Section: Curation Policies

Week 13, Day 25

Monday, November 19

Are Video Games Art?

• Roger Ebert, “Video Games Can Never Be Art,” Chicago Sun Times, April 16, 2010, http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/2010/04/video_games_can_never_be_art.html

• Mike Snyder, “Are Video Games Art? Draw Your Own Conclusion,” USA Today, March 12, 2012, http://www.usatoday.com/life/lifestyle/story/2012-03-12/video-games-smithsonian/53502696/1

• Ian Bogost, “Art,” How to Do Things With Video Games (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), pp. 9-17.

• The Art of Video Games, Smithsonian American Art Museum, http://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/archive/2012/games/

Wednesday November 21 NOTE: NO CLASS. Today is part of Thanksgiving holiday.

Week 14, Day 27

Monday November 26

Is Print Culture Dying?

• Sven Birkerts, “Resisting the Kindle,” The Atlantic, March 2009, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/03/resisting-the-kindle/7345/

• Matthew Battles, “In Defense of the Kindle,” The Atlantic, March 2009, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/03/in-defense-of-the-kindle/7346/

• Ken Auletta, “Publish and Perish,” The New Yorker, April 26, 2010, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/04/26/100426fa_fact_auletta

• Ted Striphas, “The Past and Future Histories of Books,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, March 19 2012, http://henryjenkins.org/2012/03/the_late_age_of_print_an_inter.html

Week 14, Day 28

Wednesday, November 28

Has Networked Communication Changed the Ways We Tell Stories?

• Henry Jenkins, "Transmedia Storytelling 101," Confessions of an Aca-Fan, March 22, 2007, http://henryjenkins.org/2007/03/transmedia_storytelling_101.html

• Henry Jenkins, "Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling," Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: New York University Press, 2006), pp. 93-130.

• Nick DeMartino, "Why Transmedia Is Catching On Now," Future of Film Blog, Parts 1 (July 5, 2011), 2 (July 6, 2011), 3 (July 7, 2011).

http://www.tribecafilm.com/tribecaonline/future-of-film/Why-Transmedia-is-Catching-On-Part-1.html,

http://www.tribecafilm.com/tribecaonline/future-of-film/Why-Transmedia-is-Catching-On-Part-2.html,

http:/www.tribecafilm.com/tribecaonline/future-of-film/Why-Transmedia-is-Catching-On-Part-3.html

Week 14 Discussion Section: Mapping a Transmedia Story?

Week 15, Day 29

Monday, December 3

Planning Strategy for the Exam

Week 15, Day 30

Wednesday, December 5

Complet

This article is translated to Serbo-Croatian language by Anja Skrba from Webhostinggeeks.com.

For a Polish translation, see http://www.pkwteile.de/wissen/wprowadzenie-do-technologii-komunikacyjnych