Inventing the Digital Medium: An Interview with Janet Murray (Part One)

/I first met Janet Murray when I arrived at MIT almost 25 years ago. At the time, she was working on her book, Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace, while I was working on Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. Murray, along with the members of the Narrative Intelligence Reading Group, was an early guide for me to the emerging realm of digital culture and helped to shape my thinking in ways that I will never be able to fully acknowledge. A few years later, Murray and I worked together, along with Ben Singer and Ellen Draper, to create The Virtual Screening Room, the prototype for a fully interactive digital textbook for studying film analysis. In many ways, what we constructed together using Hypercard was more advanced than anything we've seen so far coming out of the realm of e-books, with hundreds of clips on command from almost as many movies to illustrate core concepts in film editing.

Shortly afterwords, she left MIT for Georgia Tech, while with William Uricchio, I took over the leadership of our newly created Comparative Media Studies Program. We've remained in touch through the years, with Murray always proving to be a wonderful thinking partner, sometimes affirming, sometimes challenging my own thinking, and always overseeing cutting edge projects which stretched the affordances of digital media in the service of expanding human expression or more fully realizing its pedagogical potential. We've both found ourselves under attack for being "narratologists" in the famous "Ludologist" debates, and sharpened our own thinking about games as a medium in the process. I was delighted (well, for many reasons) when the British magazine, Prospect, identified both of us as among the top thinkers for the digital future.

Murray recently released her long-awaited new book, Inventing the Medium: Principals of Interaction Design as a Cultural Practice. On one level, the book is a textbook designed to help designers in training develop a fuller, more robust understanding of digital media, one which builds productively on principles she first outlined in Hamlet on the Holodeck, but which also reflects on the past decade plus of developments as many once cutting edge practices have now become normalized and routinized within digital media. This book captures some of the thinking she did as the chair of her program at Georgia Tech, which remains one of the most forward thinking about new media platforms and practices.

On another level, the book is a theory of media -- especially of media change -- with a strong emphasis on the intersections between technology and culture. I was delightful to see how much more deeply Murray had read and thought about media theory since the first book, and in the process, she is pushing all of us to think more deeply about what it might mean to consider the digital as its own medium rather than as a delivery system for multiple media or what it might mean to think about the local choices made in digital design as contributing to a larger evolution of that medium. Murray's writing has shifted in a more technical direction than her first book, which was very much an argument for why humanists should engage with new media production and critique, but she remains very much a humanist at heart, who sees digital media as making vital contributions to our contemporary culture. Inventing the Medium is an epic accomplishment, one which we will all be mining for years to come.

In this interview, Murray reflects about the larger conceptual framing of the book, what it has to say about the nature of media change and the role of design in constructing contemporary culture. Her thoughtful and engaging responses to my questions should provoke further reflections about the state of the art in digital design.

Your earlier book, Hamlet on the Holodeck, has been described as an experiment in speculative poetics, in that you were reading early signs of what kind of affordances digital media would offer for human expression. Inventing the Medium now has several decades of experiments and innovations to draw on. How did this change the way you approached this project?

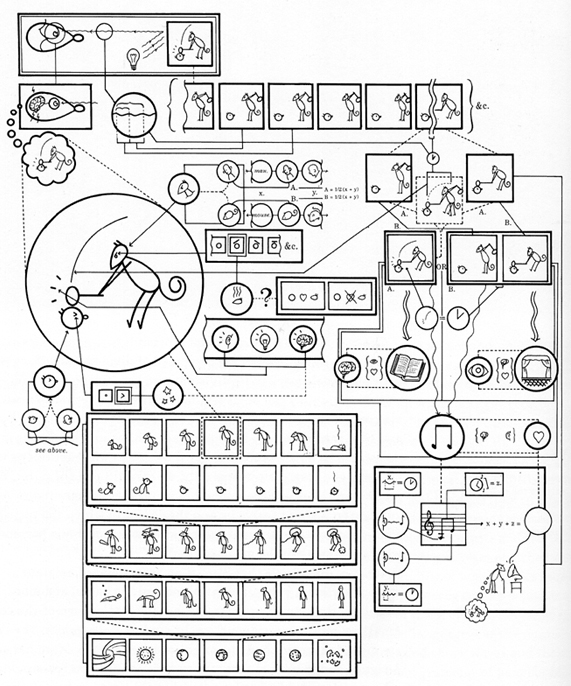

When I sat down to write Hamlet on the Holodeck (HoH) I challenged myself to prove what I believed from the day my students at MIT showed me Eliza and Zork - that this was the beginning of a new medium of expression that could be as rich as print or film. To do that, I had to step back and say what were the equivalents of the material affordances that made film a new medium and not just a way of recording plays or acting out novels. So I came up with the formulations in Chapter 3 of HoH which is probably the most widely read part of that book - that the equivalent of cutting the film and changing the focus of the lens, etc. for cinema was the procedural, participatory, encyclopedic, and spatial affordances of the computer as a medium of representation.

At that point my interest was just in talking about these 4 properties as affordances for storytelling, but it immediately became clear to me in my work as an interaction designer, leading educational computing and (what would now be called) "digital humanities" projects that talking about these affordances and the aesthetics of interactivity and immersion that come out of them was a great way of focusing design teams and conceptualizing key design choices.

So the new book picks up that focus on the design process itself, and it looks beyond narrative to see the design of any digital artifact - any device, web page, app, archive, based on electronic bits and running code - as part of a common enterprise that I call "Inventing the Medium."

So the new book grows out of the previous one, but it also reflects the very different experience I've had since moving to Georgia Tech in 1999 where I served as Director of Graduate Studies (2000-2010) and where I established and continue to teach courses in interaction design, game design as a cultural practice,,and interactive television for students go on to work for all the major players in digital media from Apple and Ideo to Disney Imagineering, Electronic Arts, and Zinga, to Turner Broadcasting, Showtime, DirectTV, and AOL to Google, Amazon, and IBM and so on. Working in this community of diverse creative abilities, brought me much closer to the concrete design challenges of commercial world than my work at MIT. And my contact with all those companies, as well as my work with the American Film Institute as a Mentor and Trustee throughout the heady changes of the 2000s gave me a first-hand look at how productive change can be nurtured or thwarted within a community of practice. . .

So the short answer to your question is, my core ideas from 1997 have proven quite useful despite the profound disruptions and exhilarating inventions of the past 15 years because my experience at MIT from the 1980s through 1990s anticipated a lot of the challenges that hit the wider society later. And the principles I'm always trying to teach my students and that I did my best to put down in Inventing the Medium (ITM) should last over the next several decades of change, because they are not about how to design for any particular platform, but about how to approach the digital design process itself so that decisions you make today will align with the trends of lasting innovation and solutions that you arrive at in the context of today's gizmos can teach you something and inform choices that you will make as a designer in the unknown future environment.

You describe this book as documenting "the collective cultural task of inventing the underlying medium." In what sense is this a cultural as well as a technological project? To what degree do you think designers are aware of their impact on the future of a medium as opposed to the pragmatic issues of designing an App?

In my own teaching I encourage designers to have a kind of double consciousness, sort of short-term and long-term. The short-term consciousness involves serving the immediate users - and the more specifically we can think about them the better - and honoring the constraints of the immediate task, which can mean using a specific platform or limiting functionality in some way. But another part of their mind has to be fixed on the horizon, on the immediate work as part of a larger cultural task, that draws on media conventions from the past that have made for coherent communication, and that creates a foundation of conventions that will make for ever greater coherence going forward.

I have identified design in this book as a cultural project but I think there can be a whole bookshelf or Kindle folder full of books elaborating on that idea, and taking other aspects of our understanding of human culture as starting points for understanding digital design. For me, the key cultural task is the creation of media conventions - the equivalent of the headline, the byline, the chapter division, the cinematic establishing shot or 180 degree rule - the organizing conventions that allow us to build greater complexity and expressivity into the rituals by which we share our understanding of the world and our empathy for one another.

The cultural task I have in mind is meaning-making. I think this is the same task that babies undertake and early humans must have undertaken in clapping hands in imitation of one another, in pointing to something to direct attention to it, in intentionally clapping hands in synchrony with another person. These are the the radical cultural primitives, and language, drawing, writing, print, photography, and now computation are all ways of expanding our ability to clap, to point, to think together and synchronize our minds and our behaviors.

You draw on some of the same core concepts here as in Hamlet on the Holodeck. Which ones have had to be rethought the most to reflect the actual changes which have taken place?

Well if I were writing HoH again I would have to make changes, and I intend to do something like that for my next book - sort of a Return to the Holodeck (!) But Inventing the Medium is really a matter of taking the same ideas deeper, and so I see it as continuous with HoH.. The main change is that just as I had to think deeply about the affordances of the medium for HoH in order to think about interactive storytelling as a special case of digital affordances, for ITM which focuses on digital affordances as the basis of a design process, I had to think much more deeply about what a medium is. In HoH I took "medium" for granted. For ITM I had to think about whether what I was claiming about a medium was true for other media. I actually had another 50,000 words about this that I had to cut out and condense into parts of the Introduction, Chapter 1, and the last chapter on the Game Model, because it slowed down the main argument about design too much to go into it. But I am writing more about that in other places. I gave a talk about it for the MECCSA in the UK and I'm going to be writing that up for an article in Convergence.

I have two main insights about what a medium is that I can state briefly here. One is that any medium is composed of three parts: Inscription, transmission, and representation. (I define all this in the book and summarize it in the Glossary which is also reproduced on my blog ) . The other is that the most productive paradigm for designers in thinking about a medium, to my mind, is the paradigm of focused attention.

And actually this paradigm, come to think of it, came indirectly from one of the most dramatic reactions to HoH, which was the hostility (which you received as well) from the ludologists who were trying to set off a place for Game Studies separate from what they thought of as the "hegemony" of "narratology." I found it very useful to my thinking that they foregrounded games as its own communicative and representational genre. This led me to think about the place of games in human culture, and I realized in reading Michael Tomasello and Merlyn Donald, neither of whom talk about games explicitly, that the experience of focused attention and "theory of mind" that the cognitive folks think of as distinguishing us from our primate cousins, is really the pleasure we find in synchronizing our behavior with one another - which is the essence of games.

For me it was a particularly illuminating moment when I read in Merlyn Donald's work the statement of how much human culture could accomplish without first inventing language. This was amazing to me as a hyperverbal person of course. But then it was illuminating to my thinking about what a medium is. And it led me to think of focused attention as the key to the design of a new medium.

Janet H. Murray is an internationally recognized designer and media theorist, and Ivan Allen College Dean's Professor of Digital Media at Georgia Tech where she also directs the Experimental Television Laboratory. She holds a PhD in English from Harvard University and was a pioneer of digital humanities applications at MIT in the 1980s and 1990s, moving to Georgia Tech in 1999, and serving as Director of Graduate Studies in Digital Media from 2000-2010 during which time she led the redesign of the MS curriculum and the founding of one of the first PhDs in the field. She is the author of Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace (Free Press, 1997; MIT Press 1998), which has been translated into 5 languages, and is widely used as a roadmap to emerging broadband art, information, and entertainment environments, and Inventing the Medium: Principles of Interaction Design as a Cultural Practice (MIT Press, 2011). At Georgia Tech, her interactive design projects include a digital edition of the Warner Brothers classic, Casablanca, funded by NEH and in collaboration with the American Film Institute; the Interactive Toolkit for Engineering LearningProject, funded by NSF; and a series of prototypes for the convergence of television and computation, created in collaboration with PBS, ABC , MTV, Turner, Intel, Alcatel-Lucent, and other networks and media companies. Murray is an emerita Trustee of the AFI and a current board member of the George Foster Peabody Award. In December 2010 Murray was named one of the "Top Ten Brains of the Digital Future" by Prospect Magazine.