Aca-Fandom and Beyond: Alex Juhasz, Jay Bushman, and Derek Johnson (Part Two)

/On August 9th, strewn across three time zones, Jay Bushman, Alex Juhasz, and Derek Kompare picked up where their previous segment ended, and pondered the implications of the concept of fandom via Skype chat. Derek Kompare (10:04 am):

My point at the end of our last conversation was to come in on this idea that there's more (much more) to the equation than "producers" and "fans." You and Jay were explicating some of these complex roles.

Alex Juhasz (10:07 am):

Where do you see yourself and your work along this spectrum?

Derek Kompare (10:09 am):

I came into this career via fandom (literally, as a fan of SF media, alternative music, etc.), but I see myself now as studying the broader formations of culture. That is, what larger structures and forces produce the entire concept of "media," "media consumption," and (yes) "fandom."

Alex Juhasz (10:10 am):

As a fan whose moved on, up, out, deeper, over (which word or is there another?) how did you find the tone and content of our earlier conversation, given that neither Jay nor I identify as either fan or acafan?

Derek Kompare (10:14 am):

I wouldn't say I've moved so much in any direction (I'm wary of discourses of transcendence; we're all already "dirty"!), but just have a more ambivalent relationship to it all. I still love being a fan, and the idea of fandom, but I'm more critical of the PRACTICES of fandom (and the relationships they entail). You and Jay hit on this massive blind spot in a lot of acafan discourse: what about people and forms that DON'T immediately identify with these terms? What does acafan do for them? I'd argue, not much! And thus we need a more useful concept.

Alex Juhasz (10:18 am):

I think that Jay and I agreed that: a situated, engaged practice (as makers or scholars) within a community of which one is a member or player that is facilitated by technology and is interested in a subjective, affective analysis of these activities links us both to acafandom even though the objects and feelings we both engage with might differ from those stereotypically connected to this sub-field.

Also, we both used the word "play" a lot, as Henry noted in his comments to us on our first exchange. "Play" helped me to name the life-affirming, community-producing, self-empowerment that can come from collective, situated, cultural production (including analysis). Of course this is also "serious"--when I am engaging with others in these lived and felt practice against, say, an illicit war or a deadly virus; or when my methods include the use of "theory" or perhaps the production of avant-garde and thus "hi-brow" texts.

Derek Kompare (10:29 am):

Is "life-affirming, community-producing, self-empowerment" always "play"? Is emotional affect always reducible to "fandom"? While I can certainly see the appeal and rationality of this conception on several planes (politically, emotionally, even physically), I worry that it risks cleaving away things that are NOT "play" and affect that is NOT "fandom."

To put on the curmudgeonly pol econ hat (which I hate wearing, but it's still in my closet): these terms also merge quite nicely with 21st century capitalism, in which consumption and pleasure are symbiotic. As much as I hate to go there, these discourses (including the ever-controversial "gamification") give me pause.

What about "citizenship"? What about "love"? What about following a particular religious faith? These things could be described as "fandom," but to me that's selling them way short, and reducing their possibilities to mere market transactions.

Alex Juhasz (10:39 am):

Given that I am not a fan, I heartily agree. I suppose I was trying to generous (to you, and other acafans in this dialogue). I study and make alternative culture in some (probably already regulated and predictable) defiance to corporate capitalism. Hence, I want to make from scratch, and using different vocabularies and systems, the culture I want to see given that I can't leave the one I am in and the languages and products it uses are often familiar and therefore useful. And when I do this with others against a war or about AIDS, mourning, and death, I do start from anger, or love, or a highly-educated analysis but in the activity itself we all live outside corporate capitalism's will to mollify us with its stuff. That's why I'm curious about how you make sense of your own fandom of corporate things.

Derek Kompare (10:47 am):

The genius of corporate culture is that its output can be so, so attractive and compelling. I don't just mean "seductive" in a conspiratorial way: I mean genuinely intriguing. The people who make the culture that comes out under corporate labels (e.g., DC Comics writers, JJ Abrams, Lady Gaga, the Dallas Mavericks) are artists in the broad sense of the word: talented people creating engaging material. I see that creative work, per se (i.e., the actual creative labor, regardless of content), as no different than any other cultural work, including oppositional work such as what Alex is involved with. So my fandom starts from the recognition of this talent.

However, since it is corporate culture, it gets complicated very quickly, and can never be totally separate from that. Of course what we all do (including the scholarly life) can never be completely separate from corporate culture anyway...

Alex Juhasz (10:50 am):

Understood. But without the means behind whatever talent we do or do not have, alternative producers and fans make objects which somehow pale, therefore putting the focus on process rather than product.

And of course, alternative production is entirely situated within capitalism, we simply try to find crevices where we can name different rules of engagement and different values (as is true for academia as well).

[Jay jumped in when he could due to his schedule]

Jay Bushman (10:53 am):

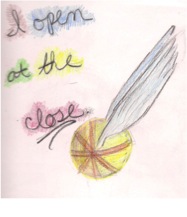

At the risk of a tangent, I liked the mention of religion above. My parents like to say that my religion growing up was "Jedi," so immersed was I in Star Wars fandom. On a functional level, it's not that ridiculous -- I'd guess that more people of my age group in the US had their morals and ethics shaped by the idea of the Force than the idea of the Holy Ghost. We joke sometimes that the Bible was the original piece of transmedia.

Alex Juhasz (10:54 am):

I just used the word "values." No tangent.

Derek Kompare (10:56 am):

The Jedi example is a great one of the complexity of corporate culture. Many people might find it blasphemous to link the Bible and Star Wars, but the affect is clearly there. Again, "fandom" risks bracketing it all off into a kind of happy/fun, harmless space, when there's always more to it (not only in terms of, say, corporate capitalism, but also, in this example, spiritual investment).

Alex Juhasz (10:59 am):

How does Henry's suggestion of the word "serious" help here?

Jay Bushman (11:00 am):

The corporate culture question is also at the root of the whole transmedia terminology debate. Lurking behind all the questions about marketing vs. storytelling vs. franchising is the split between large corporate entities and small indie producers. The example of The Matrix that Henry is fond of using to describe transmedia is far away from anything transmedia that I've been involved with.

I've always found "serious" an odd and unsatisfying term -- as if something cannot be fun and engaging and also be important at the same time.

Alex Juhasz (11:03 am):

Because you make smaller, indie things, yes? Do they also need to make money?

Jay Bushman (11:04 am):

Up until 6 months ago, I was a completely indie producer, and my projects were intentionally designed to not have a revenue generating requirement. I'm swimming in different waters now, and it has been an educational process.

Derek Kompare (11:05 am):

Agreed on "serious." We're limited by language here, which puts "serious" and "fun" on a binary, rather than on a scale, or (better) a wide plane.

Jay Bushman (11:05 am):

Re: Serious -- I view Moby-Dick as a comedy. But hey, what do I know?

Alex Juhasz (11:06 am):

I've never made anything that needs to make money because I am a Professor and am supported in this way, or I get grants or donations or I make things for super cheap. But there's no outside capitalism: just quickly evaporating places within it (like Academia).

Derek Kompare (11:09 am):

The things we make are still commodities, though, at least in part. They may not make money directly, but they are broadly "marketable" (i.e., as lines in a vita or resume, works to build up our name recognition, etc.). Kind of a tangent, but even art and academia are part of the whole system, as it's always been.

Jay Bushman (11:09 am):

I worked corporate jobs for years to support myself, while making my projects on the side. But there's a limit to the scope and scale that can be produced that way.

Alex Juhasz (11:10 am):

And aca's get paid by the University while fans do the same work (play?) and do not.

Derek Kompare (11:11 am):

Those "limits" are certainly fascinating, though. Every medium has those places, which often result in really interesting stuff (as well as a lot of crap!). As SF writer Paul Cornell said, there's no shame in producing work that only a handful of people understand or appreciate.

Great point about support systems, Alex. Again, another very valid reason to have reservations about "acafan."

Alex Juhasz (11:12 am):

Virality goes against most of what I believe in, and yet its pull is a religion of its own.

I want to start a new religion of anti-virality, non-spreadability, and local joy, but who am I kidding!

Derek Kompare (11:13 am):

"Non-spreadability"! I love it!

Alex Juhasz (11:14 am):

It was fun and serious too. Nice meeting you both.

Jay Bushman (11:14 am):

Nice to meet you too, Alex!

Derek Kompare (11:14 am):

Great to meet both of you as well!

Jay Bushman is a transmedia story designer. Writing under the name "The Loose-Fish Project," he's produced a series of Twitter-based interactive story events around subjects including Star Wars, H.P. Lovecraft and famous ghosts. Jay is also the author of The Good Captain, a Twitter-based adaptation of Herman Melville's "Benito Cereno," and Spoon River Metblog, a modernization of "Spoon River Anthology" in the form of a group blog. His essay "Cloudmaker Days: A Memoir of the A.I. Game" appeared in Well Played 2.0: Video Games, Value and Meaning from ETC Press. Jay is currently a writer/designer at Fourth Wall Studios and the co-coordinator of Transmedia Los Angeles.

Dr. Alexandra Juhasz is Professor of Media Studies at Pitzer College. She makes and studies committed media practices that contribute to political change and individual and community growth. She is the author of AIDS TV: Identity, Community and Alternative Video (Duke University Press, 1995), Women of Vision: Histories in Feminist Film and Video (University of Minnesota Press, 2001), F is for Phony: Fake Documentary and Truth's Undoing, co-edited with Jesse Lerner (Minnesota, 2005), and Media Praxis: A Radical Web-Site Integrating Theory, Practice and Politics, She has published extensively on documentary film and video. Dr. Juhasz is also the producer of educational videotapes on feminist issues from AIDS to teen pregnancy. She recently completed the feature documentaries SCALE: Measuring Might in the Media Age (2008), Video Remains (2005), and Dear Gabe (2003) as well as Women of Vision: 18 Histories in Feminist Film and Video (1998) and the shorts, RELEASED: 5 Short Videos about Women and Film (2000) and Naming Prairie (2001), a Sundance Film Festival, 2002, official selection. She is the producer of the feature films, The Watermelon Woman (Cheryl Dunye, 1997) and The Owls (Dunye, 2010). Her current work is on and about YouTube: www.aljean.wordpress.com. Her born-digital on-line "video-book" about YouTube, Learning from YouTube, is available from MIT Press (Winter 2011).

An annual attendee of both the SCMS conference and the San Diego Comic-Con, Derek Kompare is an Associate Professor in the Division of Film and Media Arts at Southern Methodist University. His research and writing is primarily focused on how media forms develop, and can be found in the books Rerun Nation: How Repeats Invented American Television (2005) and CSI (2010), several anthology and journal articles, and online at Antenna, Flow, In Media Res and (occasionally) his own blog.