Through the work of the New Media Literacies Project, we make a core distinction between the digital divide (which has to do with access to technologies -- especially networked computers and mobile telephones) and the participation gap (which has to do with access to skills and competencies required to meaningfully engage with networked culture). While there is clearly a relationship between the two, we've seen great value in decoupling them -- recognizing that one can have access to the technology without having the support structure around it which would enable you to meaningfully participate in the online world and suggesting that even schools which have little or no access to the technology might still help to foster core literacies which would allow their students some leg-up when and if they were able to gain access to networked computing. We've taken as a challenge the design of activities for low-tech and even no-tech contexts, trying to reassure teachers that ultimately it is about new conceptual models and cultural relations as much or more than it is about new technologies.

That's why I am so excited to share the following story with you. It was written by Laurel Felt, a student in USC's Annenberg School, who took my New Media Literacies class last year and has since joined our core research team. I will let her tell her own story in her own way and won't step on her punchlines here, but I hope that all of those schools and teachers who use lack of access to state of the art technology as an excuse for not changing how they teach and what students learn will read this story and perhaps think about their own situation in different terms.

Along the way, Felt builds on her research in my class to explore potential intersections between the frameworks which have emerged from the Emotional Literacy movement and those we've identified through MacArthur's Digital Media and Learning initiatives.

Take it away, Laurel.

High Tech? Low Tech? No Tech?

by Laurel Felt

We'd lost electricity... AGAIN.

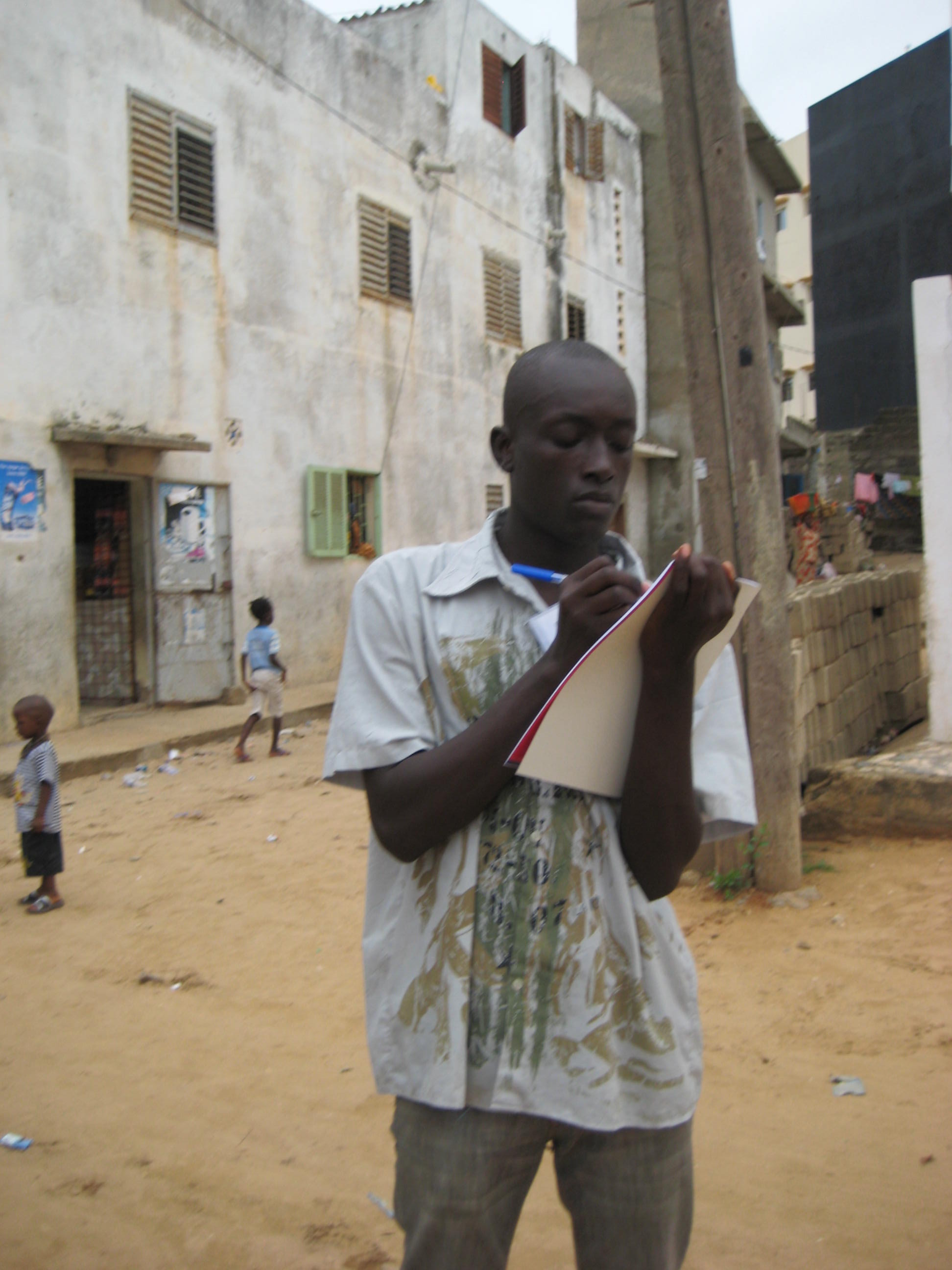

Power outages ("coupures" en francais) are hardly a novelty in Dakar, Senegal, during the early summer. Despite the fact that Dakar is Senegal's capital city, and despite the fact that Senegal is known as one of the most advanced sub-Saharan countries in terms of access to and use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), the regular but unpredictably-timed blackouts bring digital manipulation to a standstill. Lack of electricity stymies desktop computing and shuts down router-dependent Internet networks.

Those offices/apartment buildings/restaurants/hotels with the means independently purchase backup generators to see them through these periods of electrical deprivation. My workplace, the African Health Education Network (Reseau African d'Education pour la Sante (RAES)), had a backup generator.

It was broken.

After a week or two of persistent outages and incalculable loss of productivity, RAES Director Alexandre Rideau was finally able to wrangle a stop-by from the hotly-in-demand(1) generator repairman. He charged us $400, a small fortune by our non-profit organization's cash-strapped standards, and fixed yet again our mediocre, overtaxed generator. Three days later, due to negligence, the generator was blown. So it was back to the drawing board... only not quite. This time, the generator's shoddy circuitry just couldn't be salvaged. And rather than draw 10,000 non-existent dollars from RAES's red budget to buy a new generator (which was sure to be exhausted in another couple of years, or carelessly destroyed at any moment), Alex ruled that we simply had to manage this season -- powerless.

Oh, did I mention the reason I was in Senegal? To teach teens, among other things, how to harness the New Media Literacies (NMLs).

I can almost hear my fellow educators protesting that teaching NMLs in such a context is impossible. But I can testify, to my colleagues' and my relief and delight, that NMLS are precisely what are needed to survive this challenge. Since NMLs cultivate critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaboration skills, and since we, as a teaching team, had benefited from NML training before unrolling the teen workshop, we were able to construct a series of ingenious solutions. While we were powerless in a technical sense - Electrical flow? That'd be a "No" -, we were quite the opposite of "powerless" in a productive sense. Our NML training had made us powerful.

How?

Well, let me explain a bit about NMLs, and Henry Jenkins's course on New Media Literacies and discussed with Project New Media Literacies Research Director Erin Reilly, NMLs don't require technology -- they're not about technology. They're about enriching learners with useful, versatile capacities that help them think sharper, work better, and appreciate fuller the ethical ramifications of their actions.

Who can quibble with that? Who's against supporting kids' intellectual, social, and moral development? Seems like a bipartisan, big tent, "everybody on board" kind of issue to me. But a lot of people doubt the necessity of NML instruction... maybe because they misunderstand it? Maybe it's a name thing, maybe people hear the word "new," and they hear the word "media,"(2) and they think,

"Forget about it! Enough with the bells, enough with the whistles! Enough with time-sucking TECHNOLOGY! Get back to teaching little Johnny and Susie(3) good ol' fundamentals, like reading, writing, and 'rithmetic. How about teaching them how to spell, for goodness sakes?! They don't know how to write anymore!"

Noted. And I basically agree with you. But did I ever mention "technology"? No. NMLs build cultural competencies and social skills -- no technology required.

But fine, let's address technology. I mean, YOU brought it up. It's not like I'm looking to dodge the topic. ;-) Look. You can't deny that technology has entered our lives in a significant way. Personally and professionally, we're accessing digital tools and sifting cybersourced information constantly. In this new context of digital ubiquity, we especially need the critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaboration skills that we've always found handy.

Am I making sense? Here's an example: We've always needed to know how to experiment in order to figure things out. How else could we have mastered free throw shooting, can opener using, or parallel parking? But now we especially need to know how to experiment. Why? Because we're confronted with complex cell phones, tricked-out digital cameras, and bewildering new versions of Microsoft Office. Let's face it, unless you're my dad, you're just *not* gonna read the manual. If we're not comfortable pushing buttons, navigating menus, and noticing what happens, we're gonna find ourselves in a jam and/or seriously undertapping potential.

Here's another example: We've always needed to know how to respect diverse perspectives and flourish in unfamiliar environments. How else could we have moved to new towns, traveled overseas, or made friends on our first day of school? But now we especially need to know how to negotiate. Why? Because we're viewing YouTube clips from abroad, joining global communities such as Second Life and World of Warcraft, and harnessing online tools like Wikis, GoogleDocs, Salesforce and BaseCamp to manage group projects. If we're not proficient in reading and respecting people's ways of functioning, again, we'll be stuck between a rock and a hard place or flagrantly wasting opportunity. And who wants that? I'll tell you who wants that: NOBODY.

But back to Senegal.

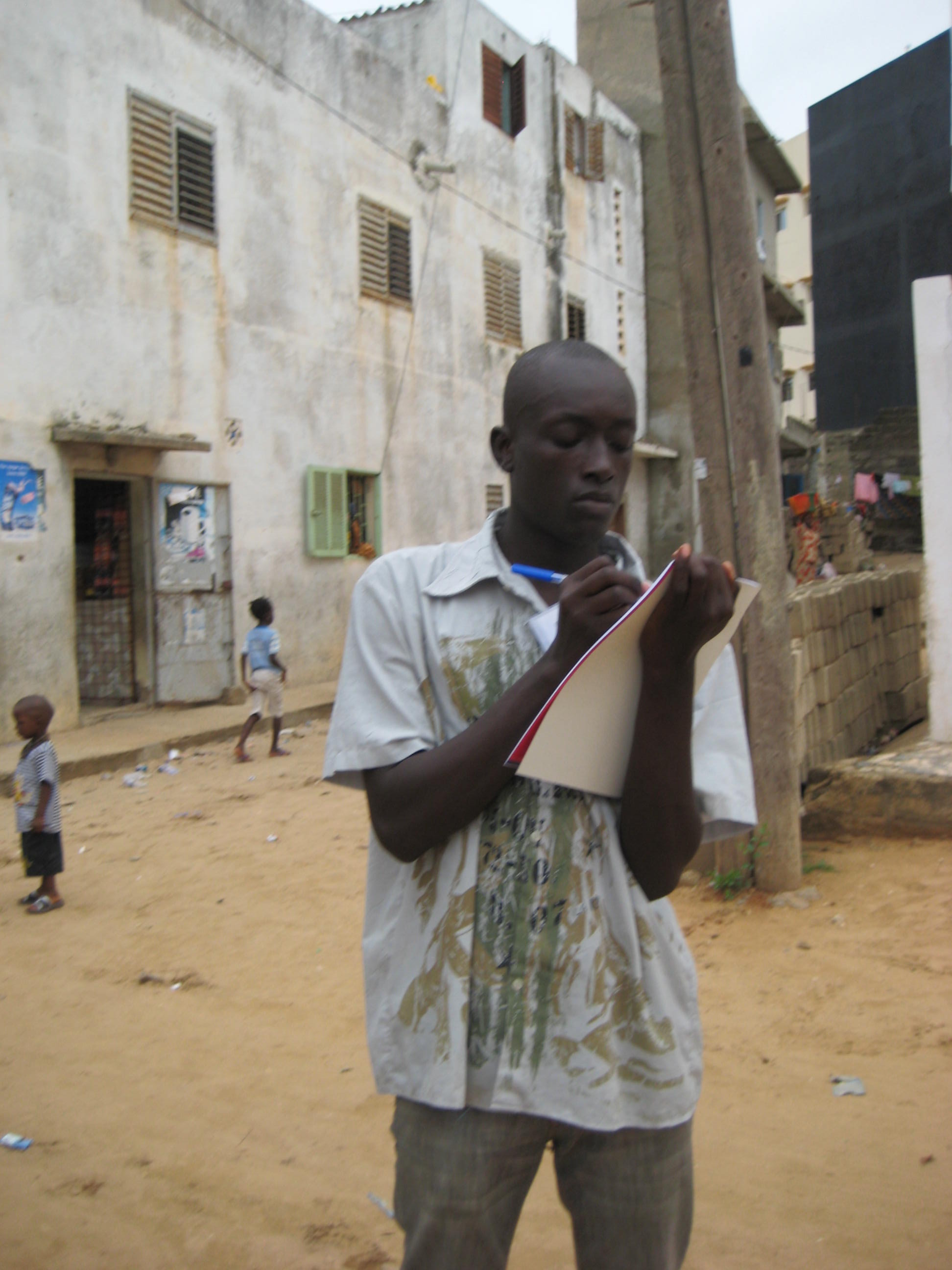

I was working for the summer as a consultant to RAES's program Sunukaddu, which means "our voice" in Senegal's indigenous Wolof language.

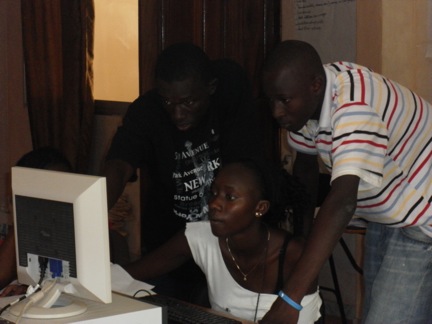

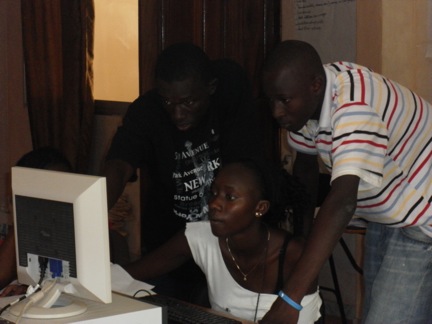

Funded over the past two years by the Soros Foundation of West Africa (OSIWA), Sunukaddu had already proven itself an innovative and effective force for social change. Its model was participatory and hands-on, connecting local media experts with motivated teens for training in multimedia health message development. Participants learned reporting and writing techniques, as well as manipulated digital cameras, camcorders, audio recording equipment, editing software, and web interfaces. Their products are online and educate all who come and click on youths' perspectives vis-à-vis HIV/AIDS. Notably, this past February, Sunukaddu ran the first public awareness media campaign by youth for youth in West Africa. Thousands of young people submitted their songs, poems, narrative films, documentaries, audio reports, articles, commentaries, and posters.. and soon this authentic content will be disseminated nationally.

Despite this demonstrable success, visionary RAES wanted to push the envelope. RAES dreamed of scaling up Sunukaddu and distributing its curriculum across West Africa. Doing so would require the construction of an explicit pedagogical method, and perhaps a re-invention of some of the ways that Sunukaddu did business...

That's when I met Alex. In our first meeting last October, Alex explained his desire for Sunukaddu to more intensively focus on storytelling, message development and diffusion. He spoke of harnessing additional, diverse media. What about pottery? What about textiles? What about dance and jewelry and cell phones? Finally, he sought to explore the human dimension of HIV/AIDS, emphasizing the relationships between and among this scourge and stigma, discrimination, community support, and human rights.

And so I began by working backwards. These new lessons and tools were Step Three. Figuring out a way to offer them so that the learning stuck was Step Two. And theorizing what was essential for any learning and growing to occur in the first place, that was Step One. So, drawing on my studies of communication, child development, and social policy, I developed a model that, at its most parsimonious, looks something like this:

New Media Literacies Improved Functioning

+

Social and Emotional Learning →

+

Asset Appreciation

Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) pairs perfectly with NMLs. In the words of Forrest Gump, they're like peas and carrots. As with the 12 NML skills, SEL's five core competencies --- self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making -- set the stage for meaningful education. In my view, SEL forms the individual, NMLs form the learner.

Back to the cries of skeptics and censurers:

"Our public school system is bankrupt and our students are falling behind. Fourth-graders in Kazkhakstan out-perform our kids in math! Most US students think Beethoven is a dog! So should we really be spending taxpayers' precious dollars on touchy-feely lessons like 'making friends' when kids can (and probably are!) learning these things themselves on the playground?"

Yes, I hear you. And yes, we absolutely should.

What are the prerequisites for learning? And what is the point of school? The first federal Bullying Prevention Summit was convened in Washington, D.C., last week. Director of Healthy School Communities (part of the Whole Child Initiative at educational leadership organization ASCD) Sean Slade summed up associate professor of child development Philip Rodkin's argument:

"Children are there [at school] to learn not only how to read, write, add, and subtract, but also how to work together as a group, a team, a community" (2010, paragraph 4).

Couldn't have said it better myself. This is proponents' rationale for teaching SEL. Sounds awfully similar to our rationale for teaching NMLs, doesn't it? And that is why SEL and NML are like peas and carrots, folks. And why life is like a box of chocolates...

Back to Senegal.

The whole Sunukaddu team agreed, Our workshops should optimize participants' engagement, appropriation, and application of the material. We should also operate as non-hierarchical partners in the learning process, and so create a context in which ideas and knowledge can flow freely in both directions.

So we developed a method that enabled learning via hands-on exploration, game play, improvisation, creation, discussion, and self-reflection. We configured these pedagogical activities such that they cultivated NMLs, SEL, and asset appreciation (a construct that I created that draws on principles from asset-based community development, appreciative inquiry, positive deviance, intrinsic motivation, and resilience). The explicit curriculum was a 12-session workshop supporting teens' efforts to access their voices, make connections, manipulate multiple communication forms and tools, and share their messages with their peers and communities.

Our original curricular outline:

DAY 1: Introduction + Basic Computer Literacy (NML skill of the day: Distributed Cognition)

DAY 2: Basic Computer Literacy + Message Development (NML skill of the day: Multitasking)

DAY 3: Message Development (Classic media literacy; NML skill of the day: Collective Intelligence)

DAY 4: Message Diffusion (Diffusion of Innovation + Stages of Change; NML skill of the day: Networking)

DAY 5: Audio (Hip hop; NML skill of the day: Appropriation)

DAY 6: Non-fiction (Journalism + Positive Deviance; NML skill of the day: Negotiation)

DAY 7: Conflict (NML skill of the day: Performance)

DAY 8: Fiction (Script-writing +Entertainment-education; NML skill of the day: Transmedia Navigation)

DAY 9: Fixed images (Photography + Peer support; NML skill of the day: Play)

DAY 10: Moving images (Cinematography + Human rights; NML skill of the day: Visualization)

DAY 11: Basic Internet Literacy (NML skill of the day: Judgment)

DAY 12: Conclusion (NML skill of the day: Simulation)

Then the power went out.

Oh yeah, remember that? ;-)

The power left the building early in the intervention, Days 1-4.(4) How do you teach basic computer literacy without computers? How do you teach distributed cognition (defined by Jenkins, Purushotma, Clinton, Weigel, and Robinson (2006) as "the ability to interact meaningfully with tools that expand mental capacities" (p. 4)) without the digital tools we'd intended?

Is it too jingoistic to holler, "New Media Literacies to the rescue!"? Probably.

Here's the answer: You harness distributed cognition and tap other tools -- we broke out the battery-powered smartphones.

You multi-task -- while the participants were filling out their asset inventories, we powwowed and rejiggered the day's schedule. You play -- along with the participants, we tested our way through this challenge, discovering what happened when we did X, Y, and Z, noting successes and setbacks, evaluating, replicating, discarding, and innovating. Like I said, the NMLs returned power to our powerless situation.

And a few days later, when Sunukaddu instructor Idrissa Mbaye hatched the idea of a Competence Clothesline, the NMLs provided an effective solution to our lack of electric fanning. Because our perceptive participants had pulled down competence cards from the line, they had in their hands... handy hand-fans. How about THAT? ;-)

So what I'm saying is, Who needs electricity when you've got skillz? And these skills don't need digital technology. What they do need are understanding, and they need sharing, with students, colleagues, parents, partners, anyone, everyone.

Now.

(1) literally - no power means no air-conditioning (not that most establishments could afford to buy or run air conditioners) and no standing fans. And this is serious in July, when average daily temperature is 81 degrees Fahrenheit and average relative humidity is 70%.

(2) and the word "literacies" - fuhgeddaboutit. Who even knows what "literacies" means? Seriously - can you define it?

(3) (nowadays, it's more like Aidan and Madison, or Muhammad and Elena)

(4) By Day 5, Alex greenlit the daily rental of a tiny generator.

Laurel Felt is a third-year doctoral student at USC's Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism who only wants to change the world... To do so, she seeks to support youths' development of new media literacies, social and emotional learning, and asset appreciation. Her research also looks at gender, obesity, bullying, and reproductive health.