ARGS, Fandom, and the Digi-Gratis Economy: An Interview with Paul Booth (Part One)

/This week marks the official release date for a new book, Digital Fandom: New Media Studies, which makes a substantial contribution to our understanding of a range of topics which run through this blog. It's author, Paul Booth, has consented to give me an interview where we talk together about the ways that he thinks Alternate Reality Games can shed light on the practices of online fandom, about how we might push beyond the opposition between producer and consumer, about how we might better understand the interplay of the commercial and gift economy as it effects fandom, and about new forms of expression which have emerged as fans work together through social networking sites.

His responses here only sample the richness of this particular book, which draws heavily on digital and literary theory, to encourage us to rethink some of the classic paradigms in fan studies. The work is cutting edge both conceptually and in terms of its range of examples (which include various forms of crowd-sourced and wiki-based forms of fan collaboration that have received limited attention elsewhere.)

The central metaphor for understanding digital fan culture comes from the world of Alternate Reality Games. What can ARGs teach us about new media platforms and processes? What do you see as the similarities and differences between fans and gamers?

To me, Alternate Reality Games are an incredible synthesis of media texts, platforms and outlets. Constructed through a variety of technologies, ARGs are paradoxical: they seem to be ubiquitous and yet they are also fleeting and ethereal. As such, it's very difficult to point to a particular space and say "this is an ARG." They seem to exist in a sort of "space between" media; that is, they are only visible through the contrast with what they are not. They seem to thrive through media camouflage. I'm reminded of the David Fincher film The Game (1997), where Nicholas Van Orton (Michael Douglas) is caught up in a game that he can't tell from reality. Events that occur in the narrative may or may not be authentic interactions, and he is never sure whether he's playing a game or actually caught up in a series of dangerous adventures.

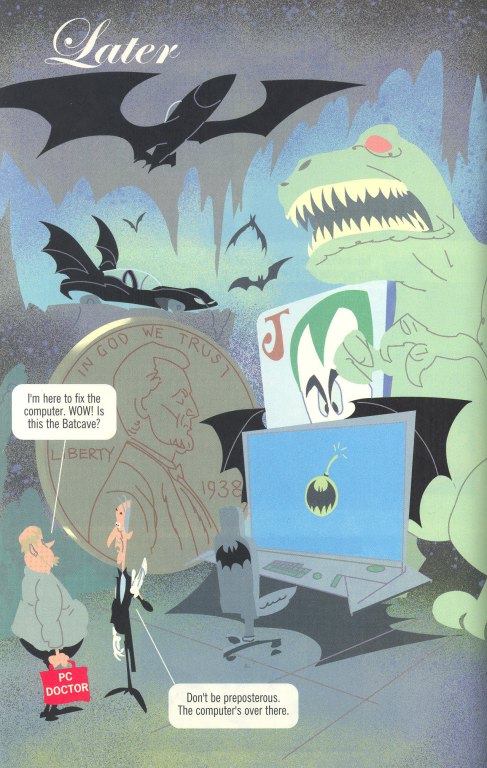

By viewing the ARG in this liminal state, we can begin to see connections to the way new media platforms and processes function in a converged media environment. That is, ARGs, like new media texts, function precisely because they exist as transmedia entities. Similarly, we're beginning to see media texts that transmediate: shows like Lost and Heroes, which tell much of their stories outside of the television; Webkinz, which takes real-world plush toys and lets children play with them in a web environment; or YA book series like The 39 Clues, which ask participants to read the book and investigate clues online.

These examples, of course, bring up another similarity between ARGs and contemporary media: the economics of them. Many ARGs exist to promote or advertise a product, as "ilovebees" promoted Halo and "The Beast" promoted the film A.I. As we embark upon a more mediatized culture, so too do we find ourselves immersed in a more commercialized culture as well.

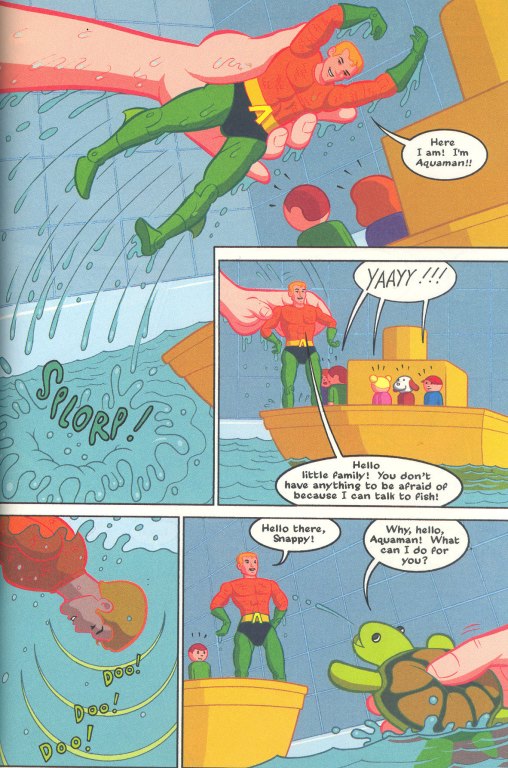

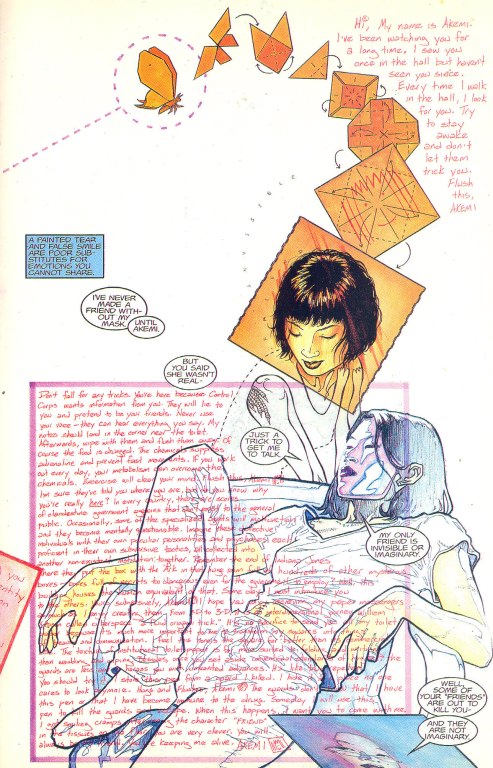

It is this connection to contemporary digital media that provides a link between ARGs and fan culture as well. I don't mean to suggest that only fans play ARGs, or that only ARGs cater to a fan base; rather, the connection is more symbolic. Fans of contemporary media and players of ARGs both interact with their requisite text in similar fashions. Fans make explicit the implicit active reading we all do when we pick up a book, watch a television show, or experience some form of media. Similarly, ARG players have to actively participate in the construction of the game itself, often uncovering hidden facets of the game, or participating in the development of narrative elements. Both for fans and for players of ARGs, the contemporary transmedia environment facilitates and encourages playfulness and engagement with many different media.

You are trying to push back on metaphors based on "market or commodity economics." What do you see as the key limits of such metaphors and how does your focus on ARGs seek to transform them?

So much of our discussion about media is based on these metaphors that we often forget that they are, indeed metaphors at all. For example, when we talk about "consumers" and "producers" of media, we're engaging in a discourse that uses gastronomic language to describe commodity economics. In other words, we talk about media in the same way that we talk about food. And the natural end result of this metaphor certainly portrays fans (and other active audiences) in a rather negative light: if media companies "produce" and audiences "consume," then what fans create through rewriting or remixing is "garbage" (or worse: a very nasty metaphor indeed). I think this metaphor ultimately limits the conversation, so even if one talks about "productive consumption," one still remains mired in this commodity mindset.

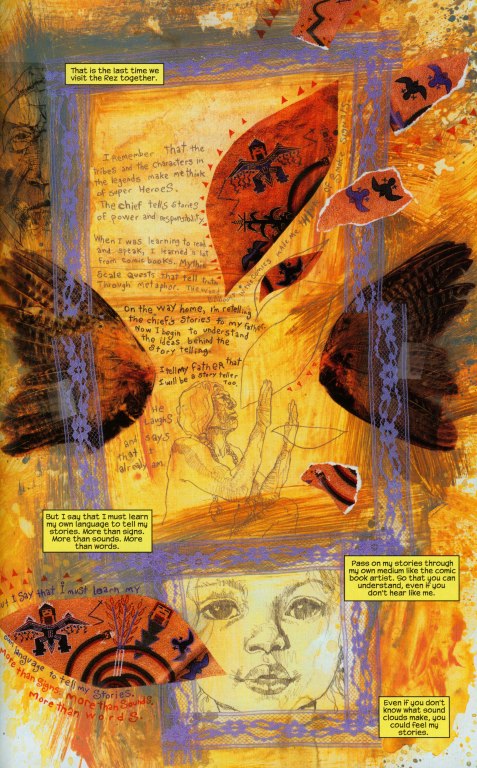

I think that while there is value in seeing media companies as "producers" and audiences as "consumers," a great deal of excellent work has also recently problematized this conception. I'm thinking of your work in Convergence Culture, Axel Bruns' research in Blogs, Wikipedia, Second life, and Beyond, and Lawrence Lessig's excellent Remix. What these books have done, and what I've tried to do in my book, is to look at the metaphors we use to describe media creation and media reception in different ways.

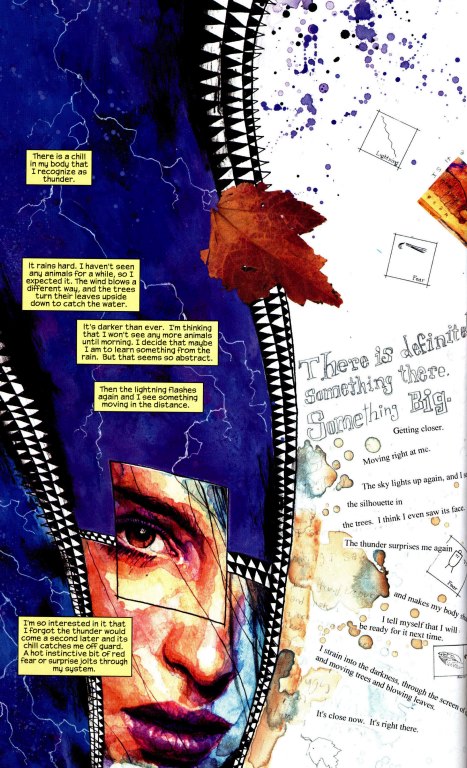

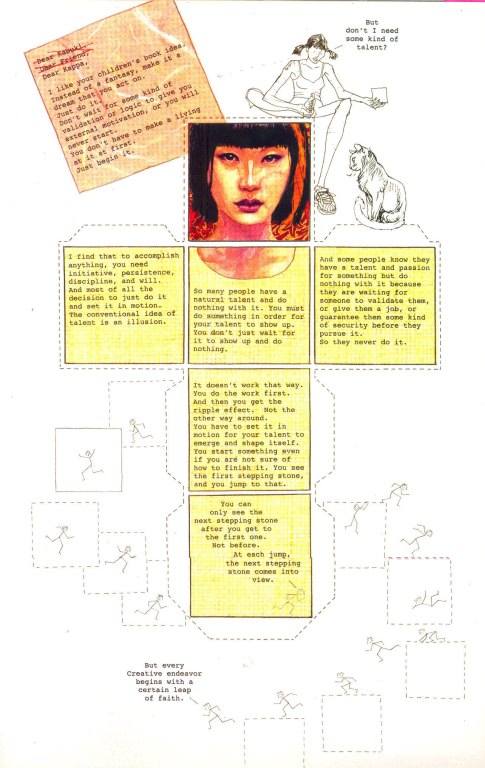

One of the main paths I follow in the book to re-look at these metaphors is to see how a different economic model - the gift economy - could work to establish a new way of describing fandom in the digital age. Both Lewis Hyde's The Gift and your blog post about the gift economy were quite influential to my thinking in this respect. In contrast to a traditional commodity economy, a gift economy values the social relationships the exchange of gifts brings. I think that if we re-examine the media creation process from a gift economy point of view, what we find is that the categories of "producer" and "consumer" simply don't function in the same way anymore. Instead of media "products" being made for "consumers," content "gifts" are exchanged between both creators and receivers. The media text is a gift, which the receiver can reciprocate through attention, feedback, fandom, or even purchasing advertised products. A gift economy metaphor implies a stronger relationship between content creators and content receivers, with more potent feedback implied between the groups. There is also a greater collaborative potential between audiences and creators, and a more fluid dynamic between the two. I certainly don't deny the economic imperative behind media consumption in general, but I think that in concert with a commodity economy metaphor, the gift economy helps create a more complete picture.

To me, ARGs represent an amalgam of the gift and the commodity economies. I've already mentioned that ARGs are often marketing campaigns, which is a strongly commoditized cultural activity. But I think it's crucial to mention that participants in ARGs can devote hours and hours of time and energy to completing the ARG without ever once purchasing the product or watching the media text the ARG advertises. When I mention I study ARGs, the most common question I receive is, "why would someone invest so much time, for free, on a game"? And I think that's a commodity way of looking at ARGs. Instead, if we look at them as gifts, we can argue that players and participants are using their time and energy to respond to the pleasures they experience in the game. The gift and the commodity economies are not enemies; but rather mutually react with each other. This union of the gift and the commodity is what I call the Digi-Gratis economy.

You discuss the emergence of a "Digi-gratis" culture which operates as a "mashup" between market and gift economies. Explain. How is this different from the hybrid economy Lawrence Lessig has discussed in some of his work?

The "Digi-Gratis" economy is a term that I use to describe the mutually beneficial relationship between the gift and the market economies within contemporary media and culture. As I was saying above, it is difficult to see either the commodity metaphor or the gift metaphor as the ultimate metaphor for understanding the relationship between media audiences and media creators. But through a lens which ties both metaphors together, we can more fully appreciate the extent of contemporary content creation.

The term "mashup" is particularly instructive here, because it implies that neither metaphor dominates the relationship. We typically think of a mashup as a sample from one text remixed with a sample from another text to form a third text. Importantly, a mashup relies on the knowledge of both requisite texts that the audience brings with it: for example, in Mark Vidler's "Carpenter's Wonderwall," the music of The Carpenters is remixed with the music of Oasis to form a unique entity, the power of which comes from that particular interaction. We have to know The Carpenters' and Oasis' original songs in order to fully appreciate Vidler's masterful mashup.

I believe that the concept of the mashup can be instructive for understanding more than media issues, and in fact can describe cultural concerns as well. The "Digi-Gratis" economy is one such mashup. As the name implies, it becomes most relevant in observing the way audiences and creators interact in digital environments. The "Digi-Gratis" economy thrives because neither the gift nor the commodity economy outweighs the other. Instead, through mutual reciprocity, their mashup forms a third type of encounter - the "Digi-Gratis." In many ways, it is similar to Lessig's conception of the hybrid economy, insofar as it does describe an interaction between two different economic styles, and that this interaction blossoms through digital technology.

But one crucial difference between the hybrid and the "Digi-Gratis" economies is that issue of the mashup metaphor. For Lessig, the hybrid emerges in spaces where one economy must dominate over the other. In turn, this dominance implies a focus on one end of the production/consumption dynamic. As Lessig says in Remix, the hybrid economy "is either a commercial entity that aims to leverage value from a sharing economy, or it is a sharing economy that builds a commercial entity to better support its sharing aims" (177). One always dominates.

Alternately, the "Digi-Gratis" implies a mutual relationship between the two economies, and places no emphasis between production and consumption: both are weighted equally. To give a recent example, Old Spice's use of viewer questions and the Old Spice man's (Isaiah Mustafa) answers has been a web hit on YouTube, Reddit, Twitter and other social media. To look at the interaction solely through a commodity metaphor limits the range of complex meanings available to the audience/viewers/responders. Audiences have had a powerful role to play not just in the creation of content, but in the focus of their attention as well. The "Digi-Gratis" metaphor offers a chance to view these interactions as meaningful in and of themselves, while not ignoring the complex interactions between commodities and gifts.

Biography

Paul Booth, Assistant Professor of new media and technology at DePaul University, is a passionate follower of new technological trends, memes, the viral nature of communication on the web, and popular culture (especially film, television and new media). He studies the interaction between traditional media and new media and the participation of fans with media texts. He received his Ph.D. in Communication and Rhetoric from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Paul teaches classes in communication and technology, popular culture, science fiction, fandom, new media, and the history of technology. His book Digital Fandom: New Media Studies investigates how fans are using "web 2.0" participation technology to create new texts online, and how their works fits into our contemporary media culture. He has also published articles in Critical Studies in Media Communication, New Media and Culture, Narrative Inquiry, The Journal of Narrative Theory, American Communication Journal, and in the book Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy. He explores topics in video games, science fiction, social media, politics, philosophy and narrative theory. He is currently enjoying a cup of coffee.