The Struggle Over Local Media: An Interview With Eric Klinenberg (Part Two)

/Early enthusiasts of digital culture celebrated an escape from the local, connecting the local with parochialism and governmental constraint. Despite such claims that we have escaped the local, we are in fact still deeply rooted in the communities where we live, work, and vote. What do you see as the continued value of the local in an increasingly global information system?

Fundamentally, its value is that it's where we are. All of us need to escape, of course, and you're right that digital culture makes getting away easy, entertaining, and often enriching, too. But most of us live profoundly local lives. Our schools, hospitals, parks, and roads play a big role in determining our quality of life, as do our cultural institutions (sorry, but it's not much fun to watch live theater or music on the Net), and the local agencies who set standards for things like air and water pollution.

This year, we're getting a crash course in how much local government matters. California is issuing IOUs to its creditors because it's out of money. New York is jacking up the price for public transportation just when its citizens can least afford it. School systems are terminating their summer programs and cutting back on teaching training. Social services for the elderly and the poor are being slashed. You might not be affected by any of this, but it's likely that someone you love is. And if you want to do something about it, isn't your local community the best place to begin?

According to a recent poll from the Pew Internet Center, fewer than half of Americans (43%) say that losing their local newspaper would hurt civic life in their community "a lot." Even fewer (33%) say they would personally miss reading the local newspaper a lot if it were no longer available. Less than a quarter of those younger than 40 (23%) say they would miss the local newspaper they read most often a lot if it were to go out of business or shut down. That compares with 33% of those ages 40 to 64 and 55% of those 65 and older. What are

the implications of this finding for those concerned about the viability of local information media?

Clearly newspapers have had a hard time proving their value to younger consumers. But I think the responses to these questions would be different if Pew had asked them differently. For instance, young people may not miss reading the local newspaper, but they would be very concerned if they could no longer get reliable local journalism online because the paper had fired so many reporters or even closed. They would notice if their favorite bloggers suddenly had less material to comment on or extend, or if their local TV news got even dumber because there was so little reporting to repackage.

If the media is an eco-system, newspaper reporting remains its sun, even in a digital age. When it diminishes, so does everything else.

Often, discussions of local media center around issues of news and information, yet your book also persistently raises questions about the impact of these trends on local and regional cultures. How might a de-emphasis on local media impact the diversity of American popular entertainment?

We've already seen the damage that media consolidation did to local music scenes. Or, rather, we've heard it, because for a decade now it has been next to impossible to find local music on the radio. Broadcasters no longer give DJs much discretion to play new sounds that aren't already established as commercially viable. For music fans, that means we can no longer use radio to expand our tastes, or to learn about innovative performers who are playing nearby. There are some new technologies that are trying to meet the constant demand for new sounds. I'm a big fan of Pandora, for instance, but it essentially gives me variations on what I already know I like. And it doesn't help me find a scene of other people who share my tastes, or let me know if a band I love has a gig where I live.

That said, I think the Net will ultimately facilitate a renaissance of local and hyper-local cultural reporting. There are already countless sites that help users find local theater, art, and music that would otherwise be difficult to identify. This kind of content is relatively inexpensive to produce, and demand for it will grow as the newspaper crisis cuts down the size of Alt Weeklies like the Chicago Reader¸ the San Francisco Bay Guardian, and the Village Voice.

One reason that I wrote Fighting for Air is that I think we can learn from our disastrous experiment with consolidation. Once we see what happens when a Clear Channel dominates radio or Gannett monopolizes newspaper markets, we can make sure that we don't make the same mistakes again. Of course, the new battle for control of media ownership has to do with telecommunications infrastructure, and issues like Net Neutrality, broadband access, and exclusivity arrangements for "smart phones" like the iPhone.

In discussions of local media, there is a tendency to act as if serving the local would necessarily serve the needs of all of the citizens. Yet, historically, local newspapers have neglected many segments of their communities and there are dispersed populations who are under-represented in any given local community who have gained greater clout by being able to connect together online. As we think about responding to the crisis in local media, how do we create institutions and practices which are more responsive to these populations?

You're right to point out the historic failings of local media organizations. They have often acted as boosters for big business and cheerleaders for local developers. Many (maybe even most) of the most celebrated outlets have long record of ignoring the poor and people of color - unless they are being presented as the source of some social problem. This is why so many entrepreneurs started "ethnic newspapers" in cities across the country. And it's why some enthusiasts for new media don't mind seeing newspapers disappear.

Most media companies do a better job diversifying their coverage than they did twenty-five years ago, at least, especially when it comes to gender, race, and ethnicity. They could still do a lot better, and they are hopeless on serving the poor because they don't see the market in it.

You ask how "we" create new institutions and practices that are more responsive, and I guess my answer hinges on who that "we" is. At the Knight conference, I argued that foundations could play a greater role in supporting grassroots initiatives by communities that are not well-served by mainstream media organizations. They do some of this already, but there are some extraordinary organizations doing innovative new media projects for their communities, and they could use a boost. For teachers, the challenge is to teach media criticism and media production skills to people, young and old, in communities that don't otherwise have resources for arts education.

At the Knight conference, you advocated governmental funding as part of the solution for supporting American journalism. Can you explain your proposal? How would you respond to critics who fear that any governmental funding of news production would lead to greater restrictions on free and independent journalism?

For the past few months I've been calling for a MediaCorps program, modeled on and perhaps integrated with the popular AmericaCorps program. The motivation is simple: During the past few years we have lost hundreds of reporters who covered Statehouses and City Halls, and you'd be hard pressed to find bloggers or citizen journalists who have moved into their bureaus. The Fourth Estate is being eviscerated, at the very moment when we need it to be robust. My proposal is that we invest some public money to replenish the supply of local political reporters. After all, how expensive would be to put two reporters in every Statehouse and two more in every major metropolitan area? Not nearly as expensive as it will be to not have them, I would argue, since the disappearance of local watchdogs gives corrupt local officials the opportunity of a lifetime.

I'm open to different ideas about how to staff the positions. MediaCorps could partner with community organizations, universities, or media companies, to provide digital media training for a new generation of political reporters. It could work as a jobs program for professional reporters who recently lost their positions, or for recent graduates of journalism schools who are looking for work.

I know that some Americans are uncomfortable with public journalism. But I think MediaCorps could easily be designed so that the reporters are independent and professional, as are the journalists who work for the Public Broadcasting Service. Given the popularity of National Public Radio, and the reporters who work for its many local affiliates, I'd think that, if it's done well, MediaCorps could have wide appeal.

And, let's face it, today we have a real market failure for local political journalism. We have a strong public interest in aggressive local journalism, but the models that historically sustained local media businesses no longer work. Using public funds to subsidize journalism may not be in line with the tradition of American media. But neither is using public funds to subsidize auto manufacturers and banks.

The fight for net neutrality has been in many ways a turning point for media reform in this country. What tactics have emerged to deal with this policy debate? How do they mark the impact of a new generation of media reformers?

The fight for Net Neutrality is a turning point because it expands the battle field of media politics. Now it's not just about content providers like News Corporation or Viacom. It's also about infrastructure and delivery systems, so Comcast, AT&T, and Verizon (among others) are key players.

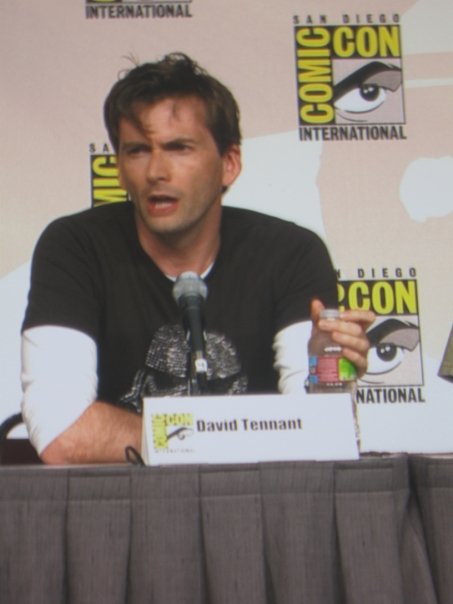

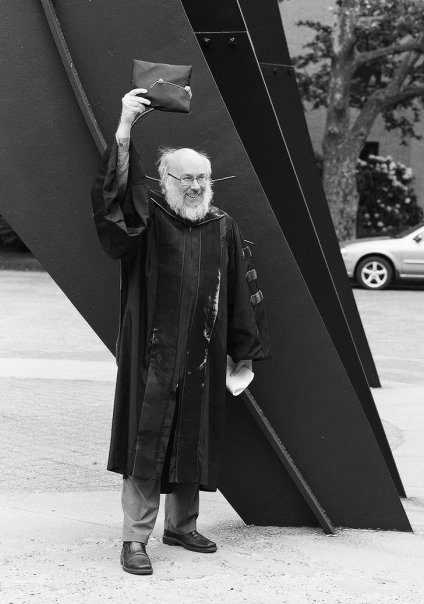

It's also a turning point because it has brought new constituencies into the media policy field: Internet enthusiasts, techies, and legal scholars (such as Larry Lessig, Tim Wu, and Jonathan Zittrain). These groups have brought terrific creative energy to what was already a dynamic social movement. They have technical expertise in law and engineering, but they also have a sense of humor, and you can see that in the Net Neutrality campaigns.

I should add that these folks are now at the center of the media reform movement. Tim Wu, who coined the term Net Neutrality, recently replaced Robert McChesney as Chairman of the Board at Free Press, and Larry Lessig keynoted the last national media reform conference, where he delivered one of his multimedia masterpiece performances. Even before these folks came on board, Free Press helped engineer the SavetheInternet campaign, a collaborative effort that involved the clever use of Web videos, political humor, a petition, and some old fashioned policy advocacy on the Hill. It was an incredible effort, and it actually changed the outcome of the telecommunications industry's first major push to win the right to discriminate against consumers and competitors. The fight is hardly over, of course, but it's remarkable how well it started.

The media reform movement has sometimes aligned itself with cultural conservatives who raise concerns about "decency" in media, concerns which are often directed at increased government regulation of media content. What do you see as the implications of that alignment? Is it possible to reconcile the goal of a diverse and independent media with the push towards government regulation of media content?

You chose the right word here. The relationship between media activists on the left and the right is usually hostile, but when they agree - as they did on issues of local control and on the critique of consolidation - they tend to form alignments and not deep bonds. They don't strategize together, or at least not often. They don't participate in each other's conferences. They don't try to reconcile their philosophical differences. And that's probably good, because they would be impossible to work out. But they do forge temporary coalitions, and these coalitions can be powerful during specific battles.

In the campaign to fight against more media consolidation, for instance, the religious right got attention for complaining about content: Janet Jackson's nipple, Howard Stern's tongue, etc. But they were also motivated by the declining independence of local broadcasters, who lost their ability to preempt network programming for local shows (often religious or athletic events) after the networks got the upper hand in negotiations; and by the anti-choice policies of cable operators who forced consumers to purchase large bundles of channels, which inevitably include several that no one wants, rather than individual stations on an a la carte basis.

The left had its own concerns about content. At the FCC's cross-national localism hearings, citizens from big cities and small towns alike spoke out against radio DJs who made lewd comments or laughed about violence against women or ethnic minorities, warned against the dangers of excessive commercialism in entertainment culture, and demanded that Big Media companies give more air time to progressive voices. They, too, linked these complaints to a critique of media ownership patterns. But in their case, the villains were Clear Channel, the News Corporation, General Electric, and the Sinclair Broadcast Group, not the so-called "cultural elites" in New York City and Hollywood.

In my view, media reformers acted responsibly in the coalition. They agreed to work with the NRA and the Parents Television Council, but only in the debate about ownership. I don't know of any media reformers who supported the FCC's policy of arbitrarily fining broadcasters for indecency. In fact, I don't know any savvy media reformers who support reinstituting the Fairness Doctrine. Content regulation just isn't a viable response to the 21st century media system. But I don't have a problem with forging provisional coalitions with those who think it is.

In some recent writings, I've been exploring whether those of us who come from cultural studies and have been interested in issues of agency and participatory culture might find ways to align with the interests of those who come from political economy or media policy and stress the structural constraints around media ownership. Both seem to agree that we are at a key turning point in the media ecology. Do you see points of contact between the two perspectives and agendas?

By all means! And since the media ecology clearly is at a key turning point, there's never been a better time for these groups to come together. Truth is, they're already fighting on the same side. Consider the remarkable fact that Robert McChesney (the leading scholar of media political economy) created an organization that has been wildly successful at promoting participation and enabling agency in all kinds of media debates. Or that innovative cultural producers, from the zany pirate broadcasters at the Prometheus Radio Project to the leaders of the Future of Music Coalition, have forged tight working relationships with wonky policy advocates like the Media Access Project.

One of my goals in Fighting for Air was to illustrate how creative, spirited, fun, and even funny the media policy movement has become, while also showing how smart, politically savvy, and intellectually serious communities of cultural producers have been in battles of all kinds. If the people involved in making media and media policy have been able to recognize their shared interests (and fate), shouldn't those of us who study them, too?