From Production to Produsage: Interview with Axel Bruns (Part One)

/I have long regarded the Creative Industries folks at Queensland University of Technology to be an important sister program to what we are doing in Comparative Media Studies at MIT. Like us, they are pursuing media and cultural studies in the context of a leading technological institution. Like us, they are adopting a cross-disciplinary approach which includes the possibility of productive exchange between the Humanities and the business sector. Like us, they are trying to make sense of the changing media landscape with a particular focus on issues of participatory culture, civic media, media literacy, and collective intelligence. The work which emerges there is distinctive -- reflecting the different cultural and economic context of Australia -- but it complements in many ways what we are producing through our program. I will be traveling to Queensland in June to continue to conversation. Since this blog has launched, I have shared with you the reflections of three people currently or formerly affiliated with the QUT program -- Alan McKee; Jean Burgess

; and Joshua Green, who currently leads our Convergence Culture Consortium team. Today, I want to introduce you to a fourth member of the QUT group -- Axel Bruns.

Thanks to my ties to the QUT community, I got a chance to read an early draft of Bruns's magisterial new book, Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage (New York: Peter Lang, 2008), and I've wanted for some time to be able to introduce this project to my readers. Bruns tackles so many of the topics which I write about on the blog on a regular basis -- his early work dealt extensively on issues of blogging and citizen journalism and he has important observations, here and in the book, about the future of civic media. He has a strong interest in issues of education and citizenship, discussing what we need to do to prepare people to more fully participate within the evolving cultural economy. As his title suggests, he is offering rich and nuanced case studies of many of the core "web 2.0" sites which are transforming how knowledge gets produced and how culture gets generated at the present moment. He has absorbed, engaged with, built upon, and surpassed, in many cases, much of the existing scholarly writing in this space to produce his own original account for the directions our culture is taking.

In this interview, you will get a sense of the scope of his vision. In this first installment, he lays out his core concept of "produsage" and explains why we need to adopt new terms to understand this new model of cultural production. In the second part, he will explore its implications for citizenship and learning.

So, let's start with the obvious question. What do you mean by produsage? What are its defining traits?

Why coin a new and somewhat awkward word to refer to this phenomenon? How does Produsage differ from traditional models of production?

I'd like to answer these in combination if I may - the question "do we really need a new word to describe the shift of users from audiences to content creators?" is one I've heard a few times as people have begun engaging with the book, of course.

There's been some fantastic work in this field already, as we all know - from Yochai Benkler's work on 'commons-based peer production' to Michel Bauwens's 'p2p production', from Alvin Toffler's seminal 'prosumers' (whose exact definition has shifted a few times over the past decades as his ideas have been applied to new cultural phenomena) to Charles Leadbeater and Paul Miller's 'Pro-Ams'. I think it's fair to say that most if not all of us working in this field see these developments as an important paradigm shift - a "leap to authorship" for so many of the people participating in it, as Douglas Rushkoff has memorably put it.

But at the same time, it's no radical break with the past, no complete turning away from the traditional models of (information, knowledge, and creative) production, but a more gradual move out of these models and into something new - a renaissance and resurgence of commons-based approaches rather than a revolution, as Rushkoff describes it; something that may lead to the "casual collapse" of conventional production models and institutions, as Trendwatching.com has foreshadowed it.

I think that ironically, it's this gradual shift which requires us to coin new terms to better describe what's really going on here. A fully-blown revolution simply replaces one thing with another: one mode of governance (monarchy) with another (democracy); one technology (the horse-drawn carriage) with another (the motorcar). In spite of their different features, both alternatives can ultimately be understood as belonging to the same category, and substituting for one another.

A gradual shift, by contrast, is less noticeable until what's there today is markedly different from what was there before - and only then do we realise that we've entered a new era, and that we have to develop new ways of thinking, new ways of conceptualising the world around us if we want to make good sense of it. If we continue to use the old models, the old language to describe the new, we lose a level of definition and clarity which can ultimately lead us to misunderstand our new reality.

Over the past years, many of us have tried very hard to keep track of new developments with the conceptual frameworks we've had - which is why even work as brilliant as Benkler's has had to resort to such unwieldy constructions as 'commons-based peer production' (CBPP), and similar compound terms from 'user-led content creation' to 'consumer-generated media' abound.

Now, though, I think we're at the cusp of this realisation that the emerging user-led environments of today can no longer be described clearly and usefully through the old language only - and produsage is my suggestion for an alternative term. It doesn't matter so much what we call it in the end, but a term like 'produsage' provides a blank slate which we can collectively inscribe with new meanings, new shared understandings of the environments we now find ourselves in.

Why does the old language fail us? Because we've been used to it for too long. When we say 'production' or 'consumer', 'product' or 'audience', most of us take these words as clearly defined and understood, and the definitions can ultimately be traced back to the heyday of the industrial age, to the height of the mass media system. 'Production', for example, is usually understood as something that especially qualified groups do, usually for pay and within the organised environments of industry; it results in 'products' - packaged, complete, inherently usable goods. 'Consumers', on the other hand, are literally 'using up' these goods; historically, as Clay Shirky put it almost ten years ago, they're seen as no more than "a giant maw at the end of the mass media's long conveyor belt".

How do the (sometimes very random) processes of collaborative content creation, for example in something like the Wikipedia, fit into this terminology? Do they? Wikipedia may well be able to substitute for Britannica or another conventionally produced encyclopaedia, but it's much more than that. Centrally, it's an ongoing process, not a finished product - it's a massively distributed process of consensus-building (and sometimes dissent, which may be even more instructive if users invest the time to examine different points of view) in motion, rather than a dead snapshot of the consensual body of knowledge agreed upon by a small group of producers.

Similarly, are Wikipedia contributors 'producers' of the encyclopaedia in any meaningful, commonly accepted sense of the word? Collectively, they may contribute to the continuing extension and improvement of this resource, but how does that classify as production? Many individual participants, making their random acts of contribution to pages they come across or care about, are in the first place simply users - users who, aware of the shared nature of the project, and of the ease with which they can make a contribution, do so by fixing some spelling here, adding some information there, contributing to a discussion on resolving a conflict of views somewhere else. That's a social activity which only secondarily is productive - these people are in a hybrid position where using the site can (and often does) lead to productive engagement. The balance between such mere usage and productive contribution varies - from user to user, and also for each user over time. That's why I suggest that they're neither simply users nor producers (and they're certainly not consumers): they're produsers instead.

So having said all of this, let me get back to your first question: What do you mean by produsage? What are its defining traits?

I define produsage as "the collaborative and continuous building and extending of existing content in pursuit of further improvement", but that's only the starting point. Again, it's important to note that the processes of produsage are often massively distributed, and not all participants are even aware of their contribution to produsage projects; their motivations may be mainly social or individual, and still their acts of participation can be harnessed as contributions to produsage. (In a very real sense, even a commercial service like Google's PageRank is ultimately prodused by all of us as we browse the Web and link to one another, and allow Google to track our activities and infer from this the importance and relevance of the Websites we engage with.)

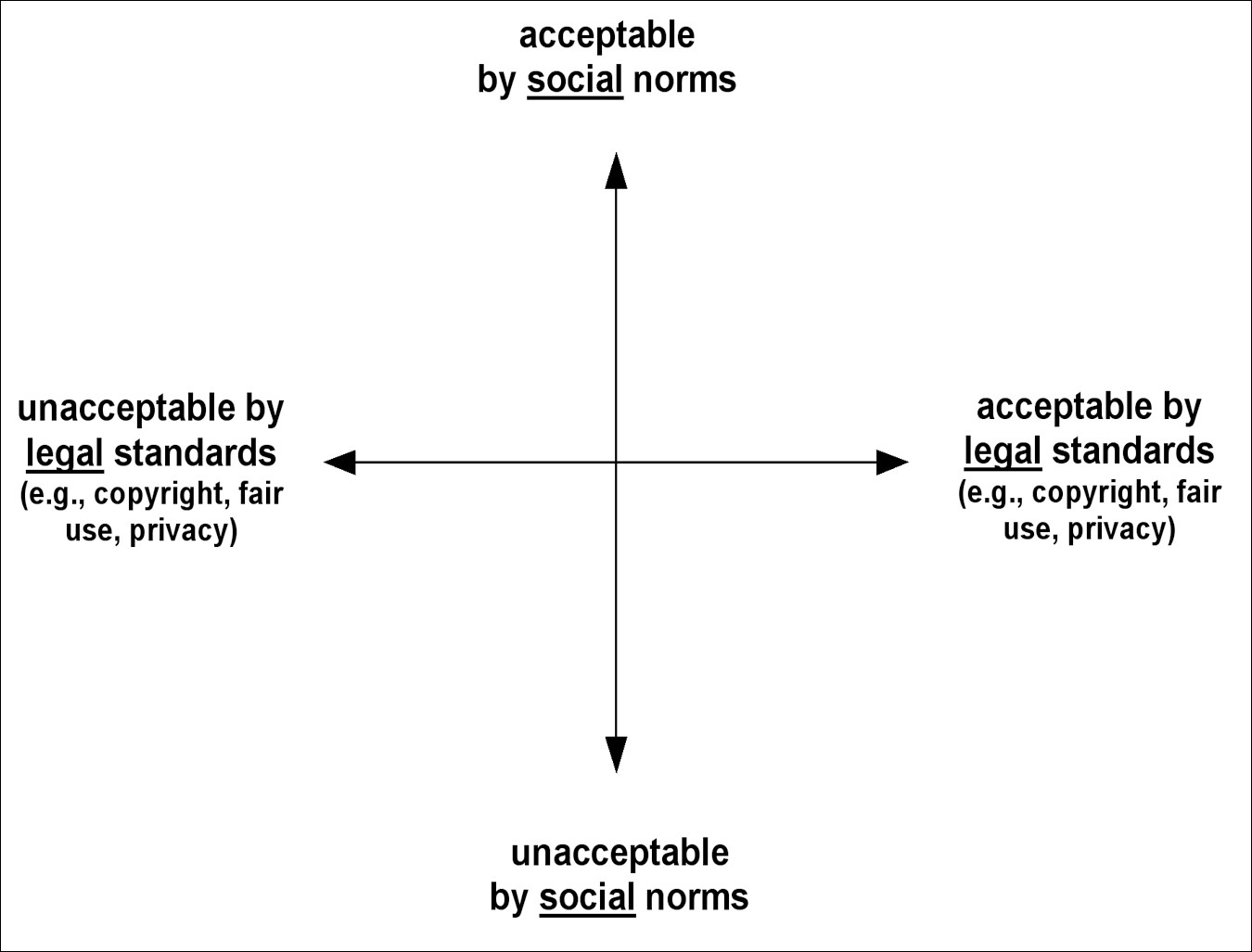

Produsage depends on a number of preconditions for its operation: its tasks must be optimised for granularity to make it as easy as possible even for random users to contribute (this is something Yochai Benkler also notes in his Wealth of Networks); it must accept that everyone has some kind of useful contribution to make, and allows for this without imposing significant hurdles to participation (Michel Bauwens describes this as equipotentiality); it must build on these elements by pursuing a probabilistic course of improvement which is sometimes temporarily thrown off course by disruptive contributions but trusts in what Eric Raymond calls the power of "eyeballs" (that is, involvement by large and diverse communities) to set things right again; and it must allow for the open sharing of content to enable contributions to build on one another in an iterative, evolutionary, palimpsestic process.

We can translate this into four core principles of produsage, then:

- Open Participation, Communal Evaluation: the community as a whole, if sufficiently large and varied, can contribute more than a closed team of producers, however qualified;

- Fluid Heterarchy, Ad Hoc Meritocracy: produsers participate as is appropriate to their personal skills, interests, and knowledges, and their level of involvement changes as the produsage project proceeds;

- Unfinished Artefacts, Continuing Process: content artefacts in produsage projects are continually under development, and therefore always unfinished - their development follows evolutionary, iterative, palimpsestic paths;

- Common Property, Individual Rewards: contributors permit (non-commercial) community use and adaptation of their intellectual property, and are rewarded by the status capital gained through this process.

I think that we can see these principles at work in a wide range of produsage environments and projects - from open source to the Wikipedia, from citizen journalism to Second Life -, and I trace their operation and implications in the book. (Indeed, we're now getting to a point where such principles are even being adopted and adapted for projects which traditionally have been situated well outside the realm of collaborative content creation - from the kitesurfing communities that Eric von Hippel writes about in Democratizing Innovation to user-led banking projects like ,Zopa, Prosper, and Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus's Grameen Bank, and beyond.)

Of course such traits are also continuing to shift, both as produsage itself continues to develop, and as it is applied in specific contexts. So, these characteristics as I've described them, and this idea of produsage as something fundamentally different from conventional, industrial, production, should themselves be seen only as stepping stones along the way, as starting points for a wider and deeper investigation of collaborative processes which are productive in the general sense of the term, but which are not production as we've conventionally defined it.

Your analysis emphasizes the value of "unfinished artifacts" and an ongoing production process. Can you point to some examples of where these principles have been consciously applied to the development of cultural goods?

My earlier work (my book Gatewatching: Collaborative Online News Production, and various related publications) has focussed mainly on what we've now come to call 'citizen journalism' - and (perhaps somewhat unusually, given that so much of the philosophy of produsage ultimately traces back its lineage to open source) it's in this context that I first started to think about the need for a new concept of produsage as an alternative to 'production'.

In JD Lasica's famous description, citizen journalism is made up of a large collection of individual, "random acts of journalism", and certainly in its early stages there were few or no citizen journalists who could claim to be producers of complete, finished journalistic news stories. Massive projects such as the comprehensive tech news site Slashdot emerged simply out of communities of interest sharing bits of news they came across on the Web - a process I've described as gatewatching, in contrast to journalistic gatekeeping -, and over the course of hours and days following the publicisation of the initial news item added significant value to these stories through extensive discussion and evaluation (and often, debunking).

In the process, the initial story itself is relatively unimportant; it's the gradual layering of background information and related stories on top of that story - as a modern-day palimpsest - which creates the informational and cultural good. Although for practical reasons, the focus of participants in the process will usually move on to more recent stories after some time, this process is essentially indefinite, so the Slashdot news story as you see it today (including the original news item and subsequent community discussion and evaluation) is always only ever an unfinished artefact of that continuing process. (While Slashdot retains a typical news-focussed organisation of its content in reverse-chronological order, this unfinishedness is even more obvious in the way Wikipedia deals with news stories, by the way - entries on news events such as the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2005 London bombings are still evolving, even years after these events.)

This conceptualisation of news stories (not necessarily a conscious choice by Slashdot staff and users, but simply what turned out to make most sense in the context of the site) is common throughout citizen journalism, where community discussion and evaluation usually plays a crucial role - and it's fundamentally different from industrial journalism's conception of stories as discrete units (products, in other words) which are produced according to a publication schedule, and marketed as 'all the news that's fit to print'.

And that's not just a slogan: it's essentially saying to audiences, "here's all that happened today, here's all you need to know - trust us." If some new information comes along, it is turned into an entirely new stand-alone story, rather than added as an update to the earlier piece; indeed, conventional news deals relatively poorly with gradual developments in ongoing stories especially where they stretch out over some time - this is why its approach to the continuing coverage of long-term disasters from climate change to the Iraq war is always to tie new stories to conflict (or to manufacture controversies between apparently opposing views where no useful conflict is forthcoming in its own account). The more genuinely new stories are continually required of the news form, the more desperate these attempts to manufacture new developments tend to become - see the witless flailing of 24-hour news channels in their reporting of the current presidential primaries, for example.

By contrast, the produsage models of citizen journalism better enable it to provide an ongoing, gradually evolving coverage of longer-term news developments. Partly this is also supported by the features of its primary medium, the Web, of course (where links to earlier posts, related stories and discussions, and other resources can be mobilised to create a combined, ongoing, evolving coverage of news as it happens), but I don't want to fall into the techno-determinist trap here: what's happening is more that the conventional, industrial model of news production (for print or broadcast) which required discrete story products for inclusion in the morning paper, evening newscast, or hourly news update is being superceded by an ongoing, indeterminate, but no less effective form of coverage.

If I can put it simply (but hopefully not overly so): industrial news-as-product gets old quickly; it's outdated the moment it is published. Produsage-derived news-as-artefact never gets old, but may need updating and extending from time to time - and it's possible for all of us to have a hand in this.

Dr Axel Bruns (http://produsage.org/) is the author of Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage (New York: Peter Lang, 2008). He is a Senior Lecturer in the ,a href="http://www.creativeindustries.qut.edu.au/">Creative Industries Faculty at Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia, and has also authored Gatewatching: Collaborative Online News Production (New York: Peter Lang, 2005) and edited Uses of Blogs with Joanne Jacobs (New York: Peter Lang, 2006). In 1997, Bruns was a co-founder of the online academic publisher M/C - Media and Culture which publishes M/C Journal, M/C Reviews, M/C Dialogue, and the M/Cyclopedia of New Media, and he continues to serve as M/C's General Editor. His general research and commentary blog is located at snurb.info , and he also contributes to a research blog on citizen journalism, Gatewatching.org with Jason Wilson and Barry Saunders.