Prohibitionists and The Moral Economy

"The world of Web 2.0 is also the world of what Dan Gillmor calls "we, the media," a world in which "the former audience", not a few people in a back room, decides what's important." - Tim O'Reilly (2005)

"Our entire cultural economy is in dire straights....We will live to see the bulk of our music coming from amateur garage bands, our movies and television from glorified YouTubes, and our news made up of hyperactive celebrity gossip, served up as mere dressing for advertising." -- Andrew Keen (2007)

Despite the apparent long-term necessity of the entertainment industry reshaping its relations with consumers (both in the face of new technological realities that make preserving traditional control over content difficult and in the face of new models of consumer relations which stress collaborations with users), media executives remain risk-averse. Andrew Currah (2006) argues that the reluctance of studio executives to risk short term revenue gains accounts for their reticence to experiment with alternative content distribution models despite growing data that suggests some forms of legal file-sharing would be in the industry's long-term best interests. Many executives at public companies are paid to draw incremental increases in revenue from mature markets rather than to adopt more long-ranging or entrepreneurial perspectives. New ventures might violate agreements media producers maintain with big-box retailers, decrease revenues from established markets (DVD, PPV), or spoil the balance of release windows and the geographic management of content distribution. According to Currah (2006, pp. 461-463), the executives best placed to authorize such changes are not likely to be around to see the long-range benefits and thus they opt for the stability and predictability of the status quo.

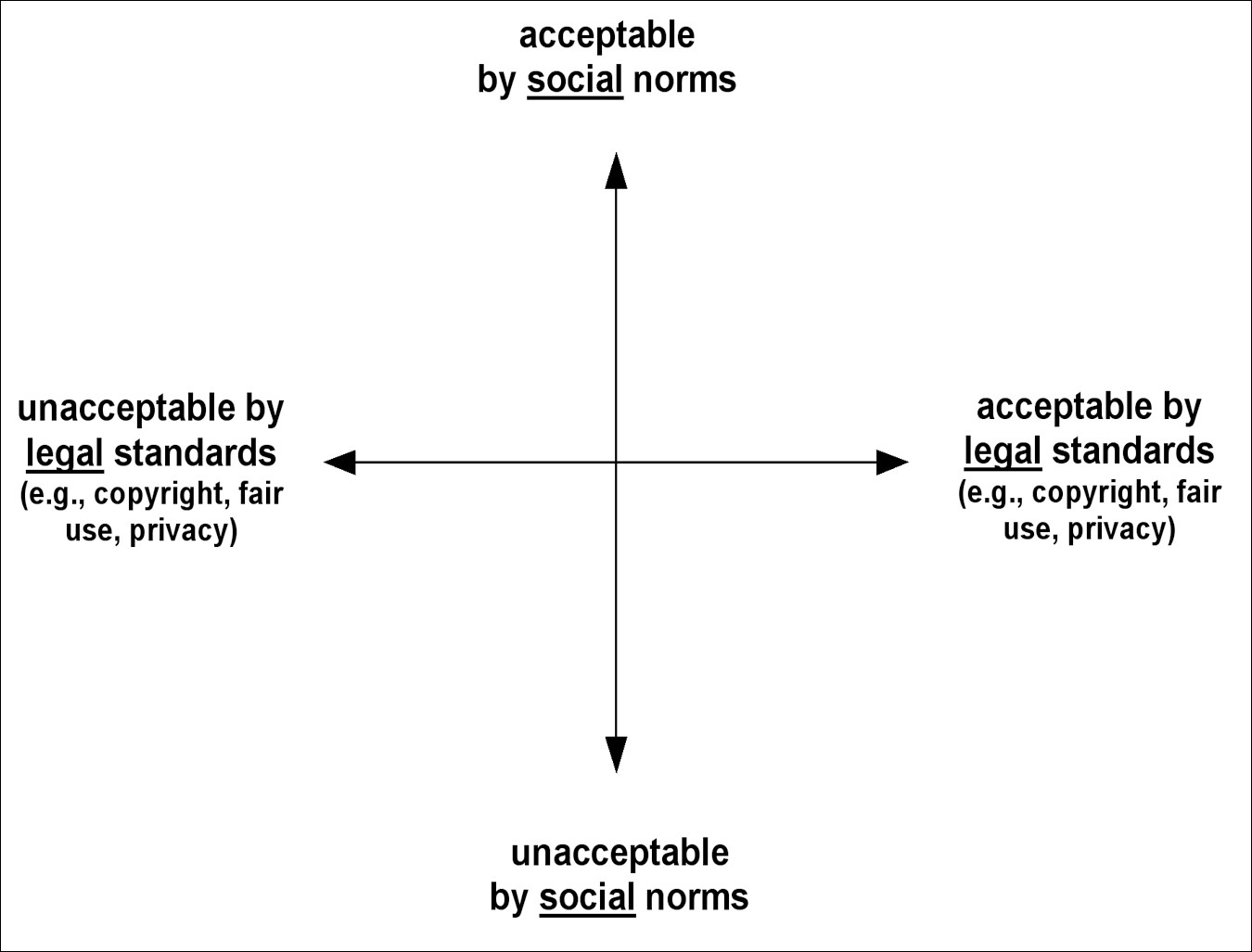

Both industry leaders and creative workers worry about a loss of control as they grant audiences a more active role in the design, circulation, and promotion of media content; they see relations between consumers and producers as a zero-sum game where one party gains at the expense of the other. For the creative, the fear is a corruption of their artistic integrity, according to what Deuze (2006) calls an editorial logic (where decisions are governed by the development and maintenance of reputations within the professional community). For the business side, the greatest fear is the idea that consumers might take something they made and not pay them for it, according to a market logic (where decisions are governed by the desire to expand markets and maximize profits). A series of law suits which have criminalized once normative consumer practices have further inflamed relations between consumers and producers.

If the hope that consumers will generate value around cultural properties has fueled the collaborationist logic, these tensions between producers and consumers motivate the prohibitionist approach towards so-called "disruptive technologies" and practices. If the collaborationist approach welcomes fans as potential allies, the prohibitionist approach sees fans as a threat to their control over the circulation of, and production of meaning around, their content. Consumers are read as "pirates" whose acts of repurposing and recirculation constitute theft. The prohibitionist approach seeks to restrict participation, pushing it from public view. The prohibitionist response needs to be understood in the context of a renegotiation of the moral economy which shapes relations between media producers and consumers.

The economic and social historian E.P. Thompson (1971) introduced the concept of "moral economy" in his work on 18th century food riots, arguing that where the public challenges landowners, their actions are typically shaped by some "legitimizing notion." He explains, "the men and women in the crowd were informed by the belief that they were defending traditional rights and customs; and in general, that they were supported by the wider consensus of the community. In other words, the relations between landowners and peasants, or for that matter, between contemporary media producers and consumers, reflect the perceived moral and social value of those transactions. All participants need to feel that the involved parties behave in a morally appropriate fashion.

Jenkins (1992) introduced this concept of "moral economy" into fan studies, exploring the ways that fan fiction writers legitimate their appropriation of series content. Through their online communication, fan communities develop a firm consensus about the "moral economy"; this consensus provides a strong motivation for them to speak out against media producers who they feel are "exploiting" their relationship or damaging the franchise. The growing popularity of illegal downloads amongst music consumers, for example, reflects the oft-spoken belief that the record labels are "ripping off" consumers and artists alike through inflated prices and poor contractual terms. The controversy surrounding FanLib spread so rapidly because the fan community already had a well articulated understanding of what constituted appropriate use of borrowed materials. Fans objected to profiting from fan fictions both because they saw their work as gifts which circulated freely within a community of fellow fans, and because they believed rights holders were more apt to take legal action to shut down their activities if money was changing hands (Jenkins 2007a).

In a review of the concept of the "moral economy" in the context of a discussion of digital rights management, Alec Austin (et. al. 2006) writes, "Thompson's work suggested that uprisings (or audience resistance) was most likely to occur when powerful economic players try to shift from existing rights and practices and towards some new economic regime. As they do so, these players seem to take away "rights" or rework relationships which were taken for granted by others involved in those transactions." A period of abrupt technological and economic transition destabilizes relations between media producers and consumers. Consumers defend perceived rights and practices long taken for granted, such as the production and circulation of "mix tapes", while corporations try to police behaviors such as file sharing, which they see as occurring on a larger scale and having a much larger public impact. Both sides suspect the other of exploiting the instability created by shifts in the media infrastructure.

This moral economy includes not simply economic and social obligations between producers and consumers but also social obligations to other consumers. As Ian Condry (2004) explains, "Unlike underwear or swim suits, music falls into the category of things you are normally obligated to share with your dorm mates, family, and friends. Yet to date, people who share music files are primarily represented in media and business settings as selfish, improperly socialized people who simply want to get something -- the fruits of other people's labor -- for free." Industry discourse depicting file-sharers (or downloaders, depending on your frame of reference) as selfish doesn't fully acknowledge the willingness of supporters to spend their own time and money to facilitate the circulation of valued content, whether in the form of a "mix tape" given to one person or a website with sound files that can be downloaded by any and all. Enthusiasts face these costs in hopes that their actions will generate greater interest in the music they love and that sharing music may reinforce their ties to other consumers. Condry says he finds it difficult to identify any moral argument against file sharing which young people find convincing, yet he has been able to identify a range of reasons why people might voluntarily choose to pay for certain content (to support a favorite group or increase the viability of marginalized genres of music). The solution may not be to criminalize file-sharing but rather to increase social ties between artists and fans.

Contemporary conflicts about intellectual property emerge when individual companies or industries shift abruptly between collaborationist and prohibitionist models. Hector Postigo (2008) has documented growing tensions between game companies and modders when companies have sought to shut down modding projects which tread too closely onto their own production plans or go in directions the rights holders did not approve. Because there has been so much discussion of the economic advantages of co-creation, modders often reject the moral and legal arguments for restraining their practice.

Some recent critics of Web 2.0 models deploy labor theory to talk about the activities of consumers within this new digital economy. The discourse of "Web 2.0" provides few models for how to compensate fan communities for the value they generate. Audience members, it is assumed, participate because they get emotional and social rewards from their participation and thus neither want nor deserve economic compensation. Tiziana Terranova (2000) has offered a cogent critique of this set of economic relationships in her work on "free labor": "Free labor is the moment where this knowledgeable consumption of culture is translated into productive activities that are pleasurably embraced and at the same time often shamelessly exploited....The fruit of collective cultural labor has been not simply appropriated, but voluntarily channeled and controversially structured within capitalist business practices."

Consider, for example, Lawrence Lessig's (2007) critique of an arrangement where LucasFilm would allow fans to "remix" Star Wars content in return for granting the company control over anything participants had generated in response to those materials. Lessig, writing in the Washington Post, described such arrangements as a modern day version of "sharecropping." Fans were embracing something like this same critique in their response to FanLib, rejecting the idea that the company should be able to profit from their creative labor.

On the other end of the spectrum fall writers like Andrew Keen (2007), who suggests that the unauthorized circulation of intellectual property through peer-to-peer networks and the free labor of fans and bloggers constitute a serious threat to the long-term viability of the creative industries. Here, it is audience activity which exceeds the moral economy. In his nightmarish scenario, professional editorial standards are giving way to mob rule and the work of professional writers, performers, and media makers is being reduced to raw materials for the masses who show growing contempt for traditional expertise and disrespect for intellectual property rights. Keen concludes his book with a call to renew our commitment to older models of the moral economy, albeit ones that recognize the new digital realities: "The way to keep the recorded-music industry vibrant and support new bands and music is to be willing to support them with our dollars -- to stop stealing the sweat of other people's creative labor" (Keen 2007, p. 188).

Lessig, Terranova, and others see the creative industries as damaging the moral economy through their expectations of "free" creative labor, while Keen sees the media audiences as destroying the moral economy through their expectations of "free" content. Read side by side, the competing visions of consumers as "sharecroppers" and "pirates" reflects the breakdown of trust on all sides. The sunny Web 2.0 rhetoric about constructing "an architecture for participation" papers over these conflicts, masking the set of choices and compromises which need to be made if a new moral economy is going to emerge.

Final Thoughts

Rebuilding this trust relationship requires embracing, rather than resisting, the changes to the economic, social, and technological infrastructure we have described. The prohibitionist stance adopted by some companies and industry bodies denies the changed conditions in which the creative industries operate, trying to force participatory culture to conform to yesterday's business practices. While prohibitionist companies want to maintain broadcast era patterns of control over content development and consumer relations, they hope to reap the benefits of the digital media space. NBC enjoyed the viral buzz that came with fans sharing the Saturday Night Live clip "Lazy Sunday" but issued a take down notice to YouTube to ensure the only copies available online came from NBC's official site (within the proximity of their branding material and advertising) (Austin et al 2006). The network's prohibition of file sharing reflects NBC's discomfort with YouTube drawing advertising revenue from consumer circulation of its content. While perhaps completely defensible within broadcast era business logic, the decision ignored the ways that the spread of this content generated viewer interest in the broadcast series. For the network, the primary if not soul value of the content was as a commodity which could collect rents from consumers and advertisers alike. In attempting to re-embed "Lazy Sunday" within the distribution logics of the broadcast era, locking down both the channel and context of its distribution, NBC also attempted to re-embed the clip within an older conception of audience impressions. Many viewers responded according to this same logic - skipping both commercials and content in favor of producers who offered them more favorable terms of participation.

Navigating through participatory culture requires a negotiation of the implicit social contract between media producers and consumers, balancing the commodity and cultural status of creative goods. While this complex balance has always shaped creative industries, NBC struck down their fans in order to resolve other business matters, such as their relationships with advertisers and affiliates, sacrificing the cultural status of creative goods for their commodity value. The alternative approach is to find ways to capitalize on the creative energies of participatory audiences. Mentos' successful management of the Mentos and soda videos that emerged online in 2006 represents a more collaborative approach. Noticing a fad around dropping Mentos mints into bottles of soda and filming the resulting eruption, Mentos permitted, supported and eventually promoted the playful use of their intellectual property. Mentos could have issued cease-and-desist notices to regulate their brand's reputation, as FedEx did after a college student built a website featuring his dorm furniture made out of free FedEx boxes (Vranica and Terhune 2006). Instead, Mentos capitalized on the cultural capital its product had acquired, collaborating with audiences to construct a new brand image. Engaging and promoting fan engagement offers media companies a more positive outcome than attempting the wack-a-mole game of trying to quash grassroots appropriation wherever it arises. Doing so also brings corporations into direct contact with lead users, revealing new markets and unanticipated uses.

The renegotiation of the moral economy requires a commitment on the part of participatory audiences to respect intellectual property rights. We see the potential of rebuilding consumers' good will when anime fans cease circulating fan subbed content when it is made commercially available or when gamers support companies that offer them access to modding tools. Collaborationist approaches recognize and respect consumer engagement while demanding respect in return. Working with and listening to engaged consumers can result in audiences who help to patrol intellectual property violations; though their investment may not be measured according to the same market logics as the production and distribution companies, fans are likewise invested in the success of creative content. In doing so, media companies not only acknowledge the cultural status of the commodities they create, they're in a position to harness the passionate energies of fans.

Bibliography

Anderson, C. (2006) The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More. Hyperion, New York.

Ang, I. (1991) Desperately Seeking the Audience. Routledge, New York.

Askwith, I. with Jenkins, H., Green, J., & Crosby, T. (2006). This is Not (Just) An Advertisement: Understanding Alternate Reality Games. Report Prepared for the Members of the MIT Convergence Culture Consortium, Cambridge.

Austin, A. with Jenkins, H., Green, J., Askwith, I., & Ford, S. (2006). Turning Pirates into Loyalists: The Moral Economy and an Alternative Response to File Sharing. Report Prepared for the Members of the MIT Convergence Culture Consortium, Cambridge.

Banks, J. (2002) Gamers as Co-creators: enlisting the Virtual Audience - A Report from the Net Face. In: Balnaves, M., O'Regan, T., & Sternberg, J. (eds.) Mobilising the Audience. University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia, pp.188-212.

________ (2005) Opening the Production Pipeline: Unruly Creators. Proceedings of DiGRA 2005 Conference: Changing Views - Worlds in Play. University of Vancouver, Vancouver.

Benkler, Y. (2006) The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Boutin, P. (2006) Web 2.0: The new Internet "boom" doesn't live up to its name. Slate, 29 March,

Brabham, D. (2008) Crowdsourcing as a Model for Problem Solving: An Introduction and Cases. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14, 75-90.

Bruns, A. (2007a) Produsage, Generation C, and Their Effects on the Democratic Process. Media in Transitions 5: Creativity, Ownership, and Collaboration in the Digital Age, MIT, Cambridge.

________ (2007b) Produsage: Towards a Broader Framework for User-Led Content Creation. Creativity & Cognition Conference: Seeding Creativity: Tools, Media, and Environments, Washington DC.

Camper, B. (2005) Homebrew and the Social Construction of Gaming: Community, Creativity and Legal Context of Amateur Game Boy Advance Development. Thesis, Comparative Media Studies Program, MIT, Cambridge.

Condry, I. (2004) Cultures of Music Piracy: An Ethnographic Comparison of the US and Japan. International Journal of Cultural Studies 7, 343-363.

Currah, A. (2006) Hollywood Versus the Internet: The Media and Entertainment Industries in a Digital and Networked Economy. Journal of Economic Geography 6, 439-468.

Dena, C. (2008) Emerging Participatory Culture Practices: Player-Created Tiers in Alternate Reality Games. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14, 41-57.

Deuze, M. (2006) Media Work and Institutional Logics, Deuzeblog.

________ (2007) Media Work. Polity, London.

Fiske, J. (1989) Understanding Popular Culture. Routledge, New York.

Ford, S. with Jenkins, H. & Green, J. (2007) Fandemonium: A Tag Team Approach to Enabling and Mobilizing Fans. Report Prepared for the members of the MIT Convergence Culture Consortium, Cambridge.

________ with Jenkins, H., McCracken, G., Shahani, P., Askwith, I., Long, G., & Vedrashko, I. (2006) Fanning the Audience's Flames: Ten Ways to Embrace and Cultivate Fan Communities. Report Prepared for the members of the MIT Convergence Culture Consortium, Cambridge.

Frank, B. (2004) Changing Media, Changing Audiences. Remarks at the MIT Communication Forum, Cambridge.

Hartley, J. (1987) Invisible Fictions: Television Audiences, Paedocracy, Pleasure. Textual Practice 1, 121-138.

Hatcher, J. S. (2005) Of Otakus and Fansubs: A Critical Look at Anime Online in Light of Current Issues in Copyright Law. Script-ed 2, 514-542.

Horowitz, B. (2006) Creators, Synthesizers and Consumers. Elatable, 17 February,

Humphreys, S., Fitzgerald, B. F., Banks, J. A., & Suzor, N. P. (2005) Fan Based Production for Computer Games: User Led Innovation, the 'Drift of Value' and the Negotiation of Intellectual Property Rights. Media International Australia incorporating Culture and Policy 114, 16-29.

Jenkins, H. (1988) Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Fiction as Textual Poaching. Reprinted in Jenkins, H. (2006) Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York University Press, New York.

________ (1992) Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. Routledge, New York.

________ (2006a) Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press, New York.

________ (2006b) From a 'Must' Culture to a 'Can' Culture: Legos and Lead Users. Confessions of an Aca-Fan. 4 October,

________ (2006c) So What Happened to Star Wars Galaxies?. Confessions of an Aca-Fan. 21 July,

________ (2006d) Snake Eyes. Confessions of an Aca-Fan. 24 August,

________ (2006e) Triumph of a Time Lord: An Interview with Matt Hills. Confessions of an Aca-Fan, 28 September,

________ (2007a) Transforming Fan Culture into User-Generated Content: The Case of FanLib. Confessions of an Aca-Fan, 22 May,

________ (2007b) Four Eyed Monsters and Collaborative Curation. Confessions of an Aca-Fan, 19 February,

Keen, A. (2007) The Cult of the Amateur: How the Democratization of the Digital World is Assaulting Our Economy, Our Culture, and Our Values. Doubleday, New York.

Koster, R. (2006) User-Created Content. Raph Koster's Website, 20 June,

Kozinets, R. (2007) Inno-Tribes: Star Trek as Wikimedia. In: Cova, B., Kozinets, R., & Shankar, A. (eds.) Consumer Tribes. Elsevier, London, pp.194-211.

Lessig, L. (2007) Lucasfilm's Phantom Menace. Washington Post, 12 July,

Leonard, S. (2005) Progress Against the Law: Anime and Fandom, with the Key to the Globalization of Culture. International Journal of Cultural Studies 8, 281-305.

Levy, P. (1997) Collective Intelligence: Mankind's Emerging World in Cyberspace. Plenum Trade, New York.

Levy, S. & Stone, B. (2006) The New Wisdom of the Web. Newsweek, 3 April, pp.46-53.

McCracken, G. (1997) Plenitude: Culture by Commotion. Periph: Fluide, Toronto.

________ (2005) 'Consumers' or 'Multipliers': A New Language for Marketing?. This Blog Sits at the Intersection of Anthropology and Economics, 10 November,

O'Reilly, T. (2005) What Is Web 2.0?: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. O'Reilly, 30 September,

Perryman, N. (2008) Doctor Who and the Convergence of Media: A Case Study in 'Transmedia Storytelling' Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14, 21-39.

Postigo, H. (2008) Video Game Appropriation through Modifications: Attitudes Concerning Intellectual Property among Modders and Fans. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14, 59-74.

Pine, B. J. and Gilmore, J. H. (1999) The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Roberts, K. (2004) Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands. Powerhouse Books, New York.

Rosen, J. (2006) The People Formerly Known as the Audience. PressThink, 27 June,

Shirky, C. (2000) RIP The Consumer,1900-1999. Clay Shirky's Writings About the Internet: Economics and Culture, Media and Community, Open Source, May, http://www.shirky.com/writings/consumer.html

Squire, K. D. & Steinkuehler, C. (2000) The Genesis of 'Cyberculture': The Case of Star Wars Galaxies. In: Gibbs, D. & Krause, K. L. (eds.) Cyberlines: Languages and Cultures of the Internet. James Nicholas Publishers, Albert Park, Australia.

Taylor, T. L. (2006) Does WoW Change Everything?: How a PvP Server, Multinational Player Base, and Surveillance Mod Scene Caused Me Pause. Games and Culture 1, 318-337.

Thompson, E.P. (1971) The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the 18th Century. Past and Present 50, 76-136.

Terranova, T. (2000) Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy. Social Text 63, 33-58. Retrieved online at: http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/technocapitalism/voluntary

Toffler, A. (1980) The Third Wave. Collins, London.

Vranica, S. & Terhune, C. (2006) Mixing Diet Coke and Mentos Makes a Gusher of Publicity. Wall Street Journal, 12 June,

Von Hippel, E. (2005) Democratizing Innovation. MIT Press, Cambridge.