Choose Your Fictions Well

/By now, hopefully, you have read Peter Ludlow's account of recent events in Second Life and perhaps have also followed along with the comments and disputes that have surrounded this post. By now, hopefully, you've started to form your own opinion about what happened, why it happened, what it all means, and perhaps, what constitutes the borders between griefing and anti-griefing in this context. The following set of comments were crafted between Ludlow and myself as we reflected on these events and what they may tell us about the interplay between fantasy and politics in virtual worlds. We hope it will provide a springboard for further discussion both on this blog and elsewhere. Choose your fictions well.

by Henry Jenkins and Peter Ludlow

In 2004, the two of us spent a lot of time reflecting on the Alphaville elections in The Sims Online. Those elections culminated in a contest between the self-declared incumbent Mr-President and Ashley Richardson, an avatar guided by a 14 year old girl from Palm Beach Florida. Initially, both of us marveled over the intensity of political activity surrounding the campaign, including a debate on national radio, and then, the aftermath of those elections, when it was discovered that the voting system had been rigged on Mr-President's behalf by notorious Alphaville mafioso, JC Soprano.

Coming so shortly after the 2000 elections, there was a sense that even in play, American democracy was broken. That was our first thought. But as we looked more closely, we discovered that the two candidates were playing very different games, understanding their investments in this online game world in very different terms -- one earnestly seeking to represent the interests of her constituency as if this were a student government election being played out on a much larger scale, the other playing a game where his transgressive fantasies of being a corrupt politico in a world controlled by organized crime could be more fully explored.

The problem was that the open-ended structure of The Sims Online, which both was and was not a game, and which supports, like James Paul Gee suggests, multiple sets of goals and multiple paths to success, did not force players to actively negotiate between competing perceptions of what was going on. Both could play their own games, explore their own fantasies, and it became an issue because their actions impinged on each other's experience and impacted a much larger community of players. In other words, at least two different games collided in that moment.

As we flash forward to this new set of entanglements involving the Justice League in Second Life, we are struggling to figure out if we've made any real progress - in terms of making more explicit the competing frames of play which shape our experiences of online worlds, in having conceptual models which help us to figure out how seriously to take player's actions within virtual worlds, or even in terms of making real any hopes we have that virtual worlds can allow us to experiment with alternative models of what democracy looks like. Clearly, Second Life is if anything even more open ended than Sims Online in terms of its capacity to support participants with very different orientations and interests. It is perhaps the best embodiment of what Yochai Benkler talks about in The Wealth of Networks -- a place where differentially motivated groups and individuals co-exist within a mixed media ecology or a shared virtual world. Clearly, both the Alphaville elections and the recent JLU incident in Second Life reflect this feature of virtual worlds --different goals and narratives can coexist -- but apparently they cannot coexist peacefully indefinitely. Eventually the diverse goals and narratives collide.

Colliding narratives are a matter of routine in large virtual sandboxes like Second Life. Furries collide with Goreans, and both collide with military roleplay groups. In one famous case reported in the Alphaville Herald, a group of refugees from World War II Online colonized Second Life and soon came into conflict with a virtual gangster known as One Song and his plans to build a megamall next to their WWII roleplay sim (a conflict which led to One Song torching their headquarters -- a scale model of the Reichschtag -- which in turn led the WWII Onliners to dress as jihaddists and attack One Song's cybersex brothel, eventually taking it offline for a while). Even the military roleplay groups can come into conflict, as when one roleplay army attacked a space age Second Life army using only muskets.

Of course whether the goals and narratives are in collision, it is fair to say that not all of them are created equal. Some are praiseworthy and some demand reflection and critique.

Consider the praiseworthy first. We are interested in the ways that participatory culture can pave the way for greater civic participation and political engagement. The point of interest is the trajectory which takes a young person from being engaged creatively and expressively with a popular culture phenomenon to being courted as a potential activist whose actions matter in the "real world." For example, consider how the members of the Harry Potter Alliance have sought to make real the fantasy identities constructed around "Dumbledore's Army" in the J.K. Rowling books -- seeking to model their real world efforts at social change on the representations of activist identities constructed across the Harry Potter franchise, including organizing public interventions in the guise of "House competitions."

Or we might point to the ways that indigenous groups and environmental activists in many parts of the world (China, Brazil, the Middle East) have adopted the identity of the Na'Vi from James Cameron's Avatar as a mask through which to engage in real world interventions. Doing so gives them an empowering fantasy which can shape their own behavior and doing so can deploy a shared vocabulary of images which may generate much greater media attention. There is of course a long history of adopting the mask of the "other," or even fictional identities, in the name of social change. Isn't there a similarity to be drawn between painting yourself blue as a Na'Vi and painting yourself red for the original Boston Tea Party? Utilizing the trappings of fictional narratives can empower us to do things in the real world that perhaps we otherwise could not.

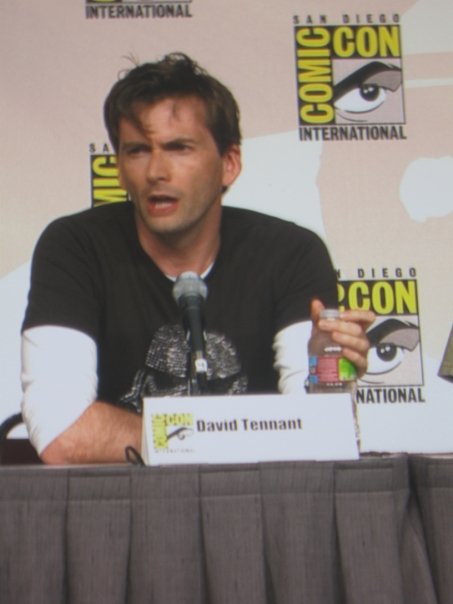

It is easy to see that the JLU incident in Second Life began with a similar sort of motives; clearly being a superhero in Second Life was an empowering fantasy for the participants. It allowed them a model of what meaningful intervention might look like and they were able to map that model onto the politics of Second Life in ways that made them feel heroic and larger than life, which empowered them to take action on behalf of their communities. Yet, at the same time, what we see is that it matters what fantasy provides your starting point.

As a long time comics fans, we can't help but note that the Justice League offers a problematic set of fantasy identities -- certainly a different set of utopian visions of political transformation, than say the characters within the Marvel Universe. The problem is that there is a kind of moral certainty which runs through the DC universe -- a sense that good guys can do no wrong, a troubling alignment of their interests with those of the state ("truth, justice, and the American way"), and a representation of pure evil in the form of the bad guys, all of which attract people with a certain way of seeing the world.

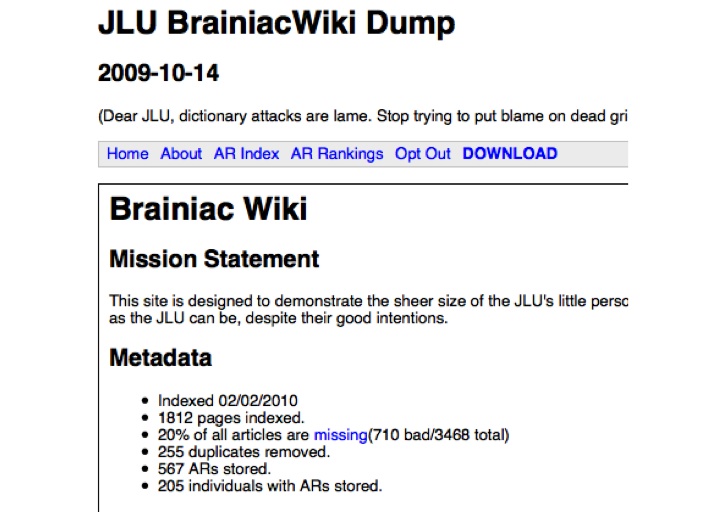

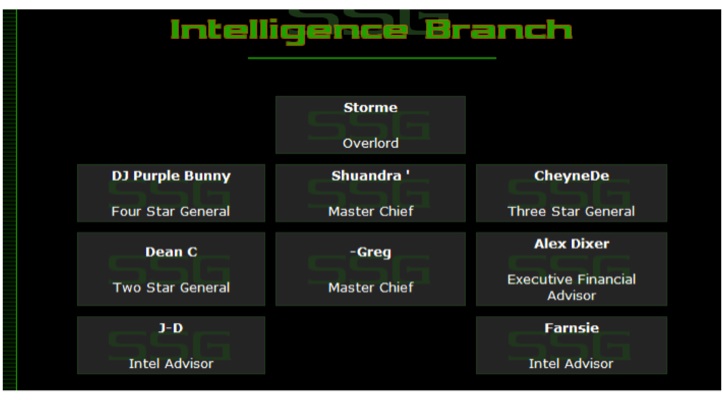

Reflecting on the consolidation of data in the JLU wiki and the violations of expectations about privacy, we cannot help but think of the ways the recent Dark Knight movie dealt with precisely the same issues: Batman can solve crimes more quickly if he can deploy surveillance equipment to spy on the citizens of Gotham City yet he faces an ethical debate about whether it is the right thing to do. The film ends up allowing him to spy on the public this one time, not to mention to take such actions as kidnapping business leaders, yet he pays a price in terms of moving back into the shadows, falling out of the good graces of the public.

It is worth pondering whether such fantasies entered into the mind of Kalel Venkman, as he pushed his campaign against griefers further and further. And we wonder what would have happened if the popular culture which inspired his particular kind of role play had adopted a different set of ethical and political values. We might ask "Who Watches the Watchmen?" though we are also reminded of Spider-man's "With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility." Both Watchmen and Spider-Man offer more complex representations of what motivates superheroes to act and what factors can or should offer a check on their relentless war against the bad guys? The problem with Superman, oddly enough, was diagnosed by Lex Luthor himself (in the recent movie), in a passage that Haruhi Thespian quoted when he informed the JLU that he was working for their enemies at Woodbury University: "Gods are selfish beings who fly around in little red capes and don't share their power with mankind. No, I don't want to be a god. I just want to bring fire to the people. And... I want my cut."

Many of the revisionist superhero fantasies which came out of the 1980s -- including those by Frank Miller and Alan Moore -- raised the question of whether superheroes helped to create the villains they battled or at least attracted them to particular geographic locations. Think about the Batman/Joker relationship: "You created me and I created you," Tim Burton told us. Would there be costumed bad guys if there were no costumed good guys?

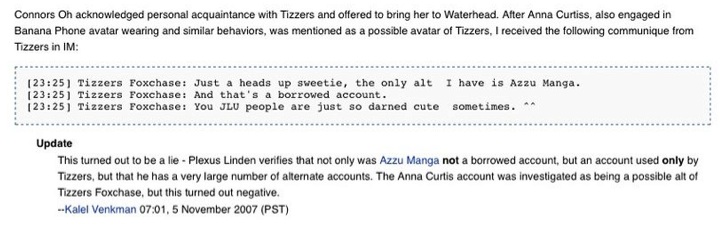

The Superhero's battle against evil becomes meaningless if there is no more evil to be battled. And so this revisionist argument goes, the Superhero starts to manufacture villains for his or her rogues gallery to fight, or perhaps, in the more fascistic versions of the superhero genre, starts to project evil onto innocent bystanders. Would the Woodbury campus on Second Life even exist without Kalel Venkman as an enemy? Woodbury leader Tizzers Foxchase has confided that he uses Kalel to keep the Woodbury kids engaged and to prevent their virtual campus from turning into the ghost town that most virtual campuses have become.

So, again, we can see what happened here as an outgrowth of a particular kind of fantasy being played out in the virtual world. Maybe Kalel Venkman even took a certain pleasure in "crossing lines," moving from the pure virtue of the classic DC superheroes towards a darker vision of the dark knight working from the shadows, doing what constitutionally regulated authorities could not do, in order to redeem a world which is otherwise beyond hope.

That said, we can only speculate on what sort of civic fantasies are at play here -- for example, what fantasies motivate the various griefer groups (the W-Hats, the channers etc) as they seek to get their LOLs by engaging in what they surely know is anti-social behavior? There is often a sense that virtual worlds allow us to enact transgressive fantasies freed of their real world consequences and if anyone objects, they are just taking things too seriously. This takes us all the way back to Julian Dibbel's "A Rape in Cyberspace" and the debate about Mr. Bungle the Clown and whether his actions are simply a form of nasty-minded play or whether they can be understood as "rape" by those most invested in their characters and the integrity of their virtual community.

On the other hand, perhaps the greifer memes about "serious business" do offer an important counterpoint to the corporate take-over of the internet. Maybe someone should take issue with the corporatist narrative about the purpose of the world wide web by offering that it ought also to be a place for play and silliness. Whether or not such lines of defense are exculpatory, they are certainly taken on by griefers, as interview after interview with griefers in the Herald has shown.

For that matter, what kinds of civic fantasies have governed the Woodbury group, with their sense of rightous indignation at being falsely accused, with their efforts to plant spies in Kalel's headquarters and thus flirt with risk? Or for that matter, what about the Alphaville Herald's conception of itself as a muckraking publication trying to rip the masks off the members of the Justice League? Are they all playing different games here or does each contribute something to the game which the others need in order to work through their fantasies, a warped version of Richard Bartle's ecology of player types?

Our point is not that these competing narratives are wrong or disingenuous, it is rather that they need to be investigated and critiqued, for these are the narratives and strategies for play that are weaving the foundations not just for virtual worlds but for our future online lives. And of course, as cases like the Harry Potter Alliance show, they also motivate our "real life" actions and attitudes.

No doubt by this point some readers are thinking that all of these people have too much time on their hands, that they are taking events in virtual worlds too seriously. This criticism actually packs two criticisms within it. First, there is the assumption that the virtual world itself is of little interest. Second there is the assumption that only the confused would use fictional narratives and trappings guide their real lives. On this latter point, no one who is using Harry Potter or the Na'vi to inspire their real life actions is confused into thinking they are wizzards or very tall blue extraterrestrial beings. Similarly, Kaleel Venkman presumably does not believe he has superman powers. These features of fictional characters do not transfer into the real world. Clearly. But what does transfer are the norms, attitudes, virtues and vices of these characters. We cannot jump over tall buildings with a single bound, but we can adopt Superman's ideas of what is right and his sense of self-certainty. The question, of course, is whether we *ought* to adopt such norms and attitudes.

As for the first question -- whether what transpires in virtual worlds matters -- this is a question that could have been intelligibly raised several years ago, but not today. Virtual worlds are rapidly becoming important platforms for work, socializing, education, and play, and given the amount of time that our children will spend in such worlds it is important to reflect on the norms that are being uploaded into those worlds today.

Clearly for virtual worlds to work they have to be open to play and experimentation, which requires suspending some of the rules that govern real world civic life. Yet, at the same time, some forms of political play fray the social contract which holds the world together, disrupting the experience of others, and destroying the infrastructure they all need in order to have meaningful experiences there. The story of the JLU invites us to ask the question -- at what point did the campaign against griefers become itself a kind of griefing, which did more to damage than to defend the integrity of other participant's virtual lives? Or to put it another way, the sandbox can allow many forms of roleplay and many competing narratives, but when the game becomes too big it impinges on the play and narratives of others. Playing well together is something we were supposed to have learned in kindergarten, but as this story shows, doing so is not as easy as it seems.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=185a3a03-6241-46e9-8e94-94f87355ac95)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6fd8f73b-d54f-4ef7-a896-4ffeb2a19c56)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=740a4070-74a1-4660-aab4-75a575e1dc7d)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=e3038901-49a5-4647-98fc-a7e6255949ea)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=00d28f2c-accc-4de6-8ee0-5b768f5a8890)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=91bbb21f-52c0-4293-a57b-4218a799a45b)