The Last Airbender or The Last Straw?, or How Loraine Became a Fan Activist

/This is another installment in our ongoing series about fan-activism and the ways certain kinds of groups are bridging between our experiences with interest-driven networks in participatory culture and public participation. This chapter tells the story of Loraine Sammy and the Racebender campaign, which challenged the white-washed casting of the feature film version of The Last Airbender. Thanks to the production chops of Anna Van Someren, we are able to share much of Sammy's story in her own words, so do take time to watch the video segments attached to this piece. As I have been working with Van Someren and Shesthova, two members of our research team, to prepare this piece for publication, I am reminded of work I did more than a decade ago around the Gaylaxians, a gay-lesbian-bi-trans science fiction fan group which made a concerted effort to get a sympathetic queer character on Star Trek: The Next Generation. The campaign failed in the short run in that the producers ultimately deflected or misdirected their requests, continually rephrasing them into how Star Trek might deal with the "issue" of gay rights, while the group wanted to show a future where being gay was not an issue. I am struck now by the growing number of science fiction series, British and American, which have matter of fact portrayals of same sex relationships, including Battlestar Galactica (whose show runner Ron Moore cut his teeth working on the Star Trek franchise.) I've never seen any one directly trace these shifts in the representation of sexuality in science fiction back to the Gaylaxians, but I have a sense that in the end, the campaign had some impact on our culture, even when its initial goal was lost. I hope the same can be said for the efforts of the Racebending efforts -- they have lost the battle but will they win the war? (For more on the Gaylaxians, see Science Fiction Audiences or Fans, Bloggers and Gamers.)

Our connection to Racebending and Loraine Sammy came through a member of the research group Lori Kido Lopez, a doctoral student at Annenberg.... who is including Racebending in her Ph.D. research.

Loraine and The Last Airbender

by Anna Van Someren and Sangita Shresthova

Loraine Sammy grew up in Vancouver, Canada reading and collecting comic books. It was her love of comics that drew her to "this new thing called the internet", where she hoped to connect with others who liked comics too. She became involved with many fandoms, including those of Star Trek and Harry Potter, and participated in several forums, mostly online. She is now conscious of the ways in which her own race, or rather its invisibility online, played out in these spaces. She also recalls how the online debates now referred to as Racefail'09, the issues surrounding race in science fiction worlds brought out by these discussions, and the people she met through this raised her awareness of racism within fantasy spaces and its impact on every day life.

Although she was a quiet observer during the Racefail discussions, Loraine's personal investment in and commitment to the fantasy worlds she loved eventually led her to take action on issues of race and representation. Like many other fans, she was captivated by the world portrayed in Avatar the Last Airbender. Nickelodeon's production of the cartoon drew heavily from Asian cultures throughout history and around the world. The meticulous research informing the characters, clothing, and practices of the tribes and characters has resulted in a show so rich and accurate in detail that teachers have been known to use it for school projects.

For some fans, the show provided the excitement of recognizing familiar cultural symbols; for others, it offered an invitation to identify, explore, and trace East Asian, Chinese, and Japanese cultural identities woven between real life and fantasy. When Paramount Pictures cast the live-action movie version of the epic, and chose white actors to play the four main characters, Loraine and many others were galvanized to take action.

"Narratives that people put faith in"

What is the role of an engaged citizen? What would a high school civics teacher most hope her students learn? Typical lists of civic competencies prioritize content knowledge about the workings of government, but are more and more likely to include intellectual skills such as "critical thinking", "perspective-taking" and dispositions such as "personal efficacy" and "desire for community involvement". Loraine is thinking about the ways in which market forces control how culture and identity get represented in society. She feels empowered enough to voice her opinion and - as we will see - transform the monologue that is the Hollywood apparatus into an open conversation across dispersed networks. How is it that a cartoon on television can motivate this kind of engagement? In our research, we're particularly interested in exactly how and why stories - often fictional - launch, support, and frame social and political movements.

At Futures of Entertainment, we recorded a conversation between Henry Jenkins and Stephen Duncombe, NYU Professor and author of Dream: Re-Imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy. Their discussion, about how we interact with narratives in ways that can motivate participation, illuminates Loraine's trajectory from a rather private engagement with popular culture to a more public engagement with society:

Democracy as Communal Creation

Fans of The Last Airbender initially organized under the slogan Aang Ain't White, using a Live Journal account to explain their argument, offer resources for joining the effort, and track their own visibility in the news. Live Journal worked well as an online headquarters, as many of the fans already had accounts at the site. Loraine herself had "a good amount of people" following her on LiveJournal, so in that way she was "able to be a trumpet for the cause".

The main strategy of Aang Ain't White was a letter-writing campaign, alerting Paramount Pictures about fans' disappointment in the casting process, and asking for the film to be re-cast. Fans also created a sister Facebook group to protest the casting.

Along with fan activist Marissa Minna Lee, Loraine worked to evolve this first campaign into the broader "Racebending" movement, and became one of the movement's primary leaders as it grew and drew in more supporters.

The existence of the Racebending campaign is "an act of communal creation" itself, and boasts an abundance of enthusiastic, active and creative production efforts. A search of the word "racebending" on Youtube yields over eighty videos, including videos like "Fighting Casting Racism", personal pledges to boycott the movie, and a slideshow called "A Brief History of Yellowface in Pictures".

A visual essay posted on the Aang Ain't White LiveJournal account inspired Youtube user chaobunny12 to produce the video essays, including Asian Culture in the Avatar World, juxtaposing images from the Airbender cartoon with images showing the Asian architecture, dress, and practices which inform and style the story world. Chaobunny's work in turn roused doldolfijntje to create a response video, similar in construction but focused specifically on comparing images of Airbender's water tribe to images depicting Inuit culture.

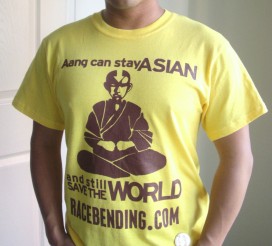

Pooling their skills in illustration and design, fanartists have created a compelling campaign of smart taglines paired with a simple representation of Aang, powerful in its recollection of street-art stenciling techniques. This collectively produced work has been distributed via postcards, banners, stickers, buttons, a visual guide to the controversy, and t-shirts.

[Read the fascinating story of the campaign's copyright battle with Viacom and Zazzle here and here].

At the 2009 San Diego Comic-Con, Racebending organizers Mike Le and Dariane Nabor invited artists to collaborate on a sketchbook, which they've now shared online. Response from the larger fan network included more creative endeavors: a comic titled "Heresies" at penny-arcade.com, blog posts at angryblackwoman.com, and more, and "a brief and incomplete history...of white actors taking strong Asian roles", featuring 10 video clips with commentary on Hyphen Magazine's blog.

Partnerships and Alliances

These actions encouraged The Last Airbender protest - specifically Racebending - to towards a network of alliances with other groups, many of which did not grow out of popular culture fandom. In particular, the Racebending's alliance with the Media Action Network for Asian Americans (or MANAA), a activist organization which advocates "balanced, sensitive and positive portrayals of Asian Americans" in American media. The collaboration with MANAA moved Racebending into a new space and group's website now indicates that they view The Last Airbender within the larger context of a systematic mis-and-under representation of minorities in media. In many ways, the alliance between Aang Ain't White and MANAA becomes a productive meeting place for two communities that mobilize and work in very different ways. Aang Ain't White emerged quickly, in response to a particular problem and is now on the cusp of more sustained political action. More established and broader in scope, MANAA also plays a watchdog role, although it relies more on actions based in protest, rather than creative production.

Through its interaction with organizations like MANAA, the Racebending movement in general and Loraine specifically now align themselves with activism around race representation. Racebending now defines it's mission as follows:

"We want Paramount Pictures - and all Hollywood studios - to know that supporting and hiring actors of color in prominent roles will help build passionate, devoted audiences. The appeal of Hollywood's films will expand with greater attention to the face of modern America." (source: Racebending)

Mobilization around The Last Airbender became a first step towards a deeper, sustained and overtly political engagement with race in popular media.

From Fandom to Activism: A "thick" politics

For Loraine, The Last Airbender became a point of entry into a growing and sustained mobilization around race in popular media. Through her deepening involvement in Racebending, Loraine journeyed from participatory culture towards an active engagement with participatory democracy. In thinking about her personal trajectory, we recall Henry Jenkins' discussion of the Digital Youth Project in "'Geeking Out' for Democracy" published in Threshold magazine:

"In a recent report, documenting a multi-year, multi-site ethnographic study of young people's lives on and off line, the Digital Youth Project suggests three potential modes of engagement which shape young people's participation in these online communities. First, many young people go on line to "hang out" with friends they already know from schools and their neighborhoods. Second, they may "mess around" with programs, tools, and platforms, just to see what they can do. And third, they may "geek out" as fans, bloggers, and gamers, digging deep into an area of intense interest to them, moving beyond their local community to connect with others who share their passions.... For the past few decades, we've increasingly talked about those people who have been most invested in public policy as "wonks," a term implying that our civic and political life has increasingly been left to the experts, something to be discussed in specialized language. When a policy wonk speaks, most of us come away very impressed by how much the wonk knows but also a little bit depressed about how little we know. It's a language which encourages us to entrust more control over our lives to Big Brother and Sister, but which has turned many of us off to the idea of getting involved. But what if more of us had the chance to "geek out" about politics?"

For Loraine "geeking out" as a fan of Avatar the Last Airbender was a key and crucial step towards "geeking out" on politics. Throughout this journey, her perspectives, approaches and motivations remain rooted in participatory culture, moving us towards a richer definition what Stephen Duncombe calls "thick politics":

In this conversation, Henry Jenkins speaks to the "changing the norms of your society rather than changing the rules of your society", and Racebending is an effort to do just that, by "advocating just and equal opportunity in film and television." For Loraine, Racebending has become journey from fandom to activism; from participatory culture to civic engagement.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=32c2f2db-1482-4b34-9502-4e2c841ae0b7)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=7b7b43e7-c1a2-4001-bada-efc82508d276)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=ec053f8e-cbb2-4747-bf27-39128120381b)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=9074b37f-9b36-4617-9945-60ace90a179b)