"What Is Civic Media" Revisited: A Conversation with Harvard's John Palfrey

/Henry Jenkins: On September 20 2007, we officially launched the MIT Center for the Future of Civic Media, a joint venture of the Media Lab and the Comparative Media Studies Program.

Our launching event include myself, Chris Csikzentmihalyi, Mitchell Resnick, Beth Noveck, and Ethan Zuckerman. At the time, Chris, Mitch and I were the co-directors of the Center. It was announced several months ago that Ethan Zuckerman would now be taking over the leadership of the lab starting this fall, and a review of the first four years of the Center's research by John Palfrey was made public. I was asked if I would be willing to participate in a conversation about the nature of Civic Media and the work of the Center with Palfrey, which will run on both my blog and the blog for the Center.

As I thought about how to initiate this conversation, I went back to my original blog post about the Center, which asked the core question, "What Is Civic Media?" And this is a question which everyone who has been affiliated with this project continues to ask. My answer at the time was deceptively simple:

Civic media, as I use the term, refers to any use of any medium which fosters or enhances civic engagement. I intend this definition to be as broad and inclusive as possible. Civic media includes but extends well beyond the concept of citizen journalism which is so much in fashion at the moment.

I left the Center when I left MIT, though I've continued to do work on civic media through my new post at the University of Southern California.

Here's how I defined the concept of Civic Media at the head of a syllabus of a class I taught last year on this topic:

Civic Media: any use of any technology for the purposes of increasing civic engagement and public participation, enabling the exchange of meaningful information, fostering social connectivity, constructing critical perspectives, insuring transparency and accountability, or strengthening citizen agency.

This much more elaborated definition reflects the conversations which took place through many meetings with the Lab's affiliated faculty, students, and researchers, especially through the exchanges I had with Ellen Hume, who was for a time the Research Director at the Lab, and Colleen Kamen, a CMS graduate student whom we asked to help think through our vision of civic media. It also has emerged through my classroom practice at MIT and now USC and more recently, my involvement in a MacArthur Research Hub focused on better understanding youth, new media, and participatory politics. For a rich snapshot of our early attempts to define "civic media," check out the series of videos at the Center's homepage.

What the two definitions share is the idea that civic media is not simply citizen journalism, a framing which seems to limit the kinds of community practices we are describing and the ways they meet the information needs of communities, to use a phrase the Knight Foundation has been exploring in recent years. Both are technology agnostic -- which is to say any set of practices around any set of technologies can become civic media if it is applied towards certain ends. The more recent definition offers some expanded sense of what those ends are which grows out of a much deeper dive into the literature around the notion of the informed citizen and around participatory politics more broadly.

From the start, I was most interested in understanding how the emergence of new media and participatory practices might be reshaping our understanding of the civic, responding to some of the disruptions of community life which had characterized the second part of the 20th century. It seemed like an important conversation to be having, and it was a key theme which emerged through the early Communication Forum events and conferences hosted by the Center.

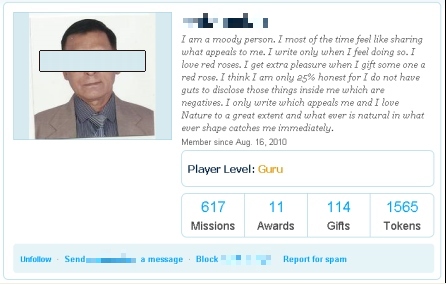

John Palfrey: Henry, I think your starting point, pushing on the definitional issue and driving from there, is right on. In my review of the Center's first four years, I worked with a close colleague, Catherine Bracy, to interview as many of the people involved in the Center as we could. Taken as a whole, the overwhelming view of the community was how valuable C4 has been in the lives of individuals involved and also in many of the environments where C4 faculty, staff, fellows, and students have been active.

A secondary finding was a hunger for understanding civic media as a concept. People had plainly been drawn to what you'd set up, even with a nascent definition; I think a lot of participants came to help in the active shaping of what it would become. I like very much your refinement over time. I've found myself, also, puzzling over the definitional issues and enjoying the process of thinking about them.

HJ: There was from the start some, hopefully productive, tension between the Media Lab participants who were strongly invested in the idea that we could design new tools which would be especially conducive to serving civic needs and the bias of the Comparative Media Studies participants who felt that we needed to be more focused on the social and cultural practices by which people integrated those tools into their everyday lives. We used to have heated debates about whether we should build the tools first and then apply them to communities or whether we should start with a deeper understanding of the community's existing practices and needs and then design to serve them better. Such debates are inevitable when working in an interdisciplinary space and could be generative or distracting depending on how well the people involved dealt with them.

JP: Yes! This productive tension jumped out of the review that we did. I think the idea of tempering one approach with another, in a way that made more of whole, is a deeply profound concept. The critical nature of the CMS discipline and the "let's go build it!" nature of the Lab's discipline have a peanut butter-and-chocolate quality to them. I think those debates have been, and can be in the future, extremely textured and important. One question I have is how C4 can tease them out and make them more public than they've been so far, so others of us can share in them somehow.

HJ:From the start, Knight wanted to keep the focus on geographically localized communities rather than more dispersed communities of interest, though we debated among ourselves how easily the two could be separated. For example, as the Center launched we were still dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans. George Lipsitz had described the working class communities of New Orleans as being "network rich and resource poor," that is to say, very strong social networks had emerged over decades which supported the sustainability of that community and insured the well-being of its members. But the hurricane had disrupted these networks on the ground, scattering the people across the country, and had done so in a way that made it difficult to imagine these communities ever being put back together again in the ways they had once functioned.

So, for me, the question was always whether we could separate out the local community in southern Louisiana from the more dispersed, diasporic community of folks from New Orleans, still strongly identified with that city, now living across the country, once part of strong social networks which they now tapped into via digital and mobile technologies. Surely, any technology-enhanced practice which strengthened the bonds between these communities would be civic media.

John Palfrey is a faculty co-director of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society, vice dean for library and information resources, and the Henry N. Ess III Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. He led a reorganization of the Harvard Law School Library in 2009. He is a principal investigator on the Open Net Initiative, a collaboration between Harvard and the University of Toronto and the University of Cambridge that studies the Internet filtering of countries such as China, Iran, and Singapore, among many others He is co-author or editor of several books, including Access Denied (MIT Press, 2008), Access Controlled (MIT Press, 2010), and Born Digital (Basic Books, 2008).